DM: Congrats on winning the 2012 National Outdoor Book Award for Almost Somewhere. I remember your working on this book when we first spoke in 2010. I’m interested in how the path of this book took shape. Can you take us through a bit of your original journey on the Muir Trail, through your development as a writer, to working on this book and its eventual publication?

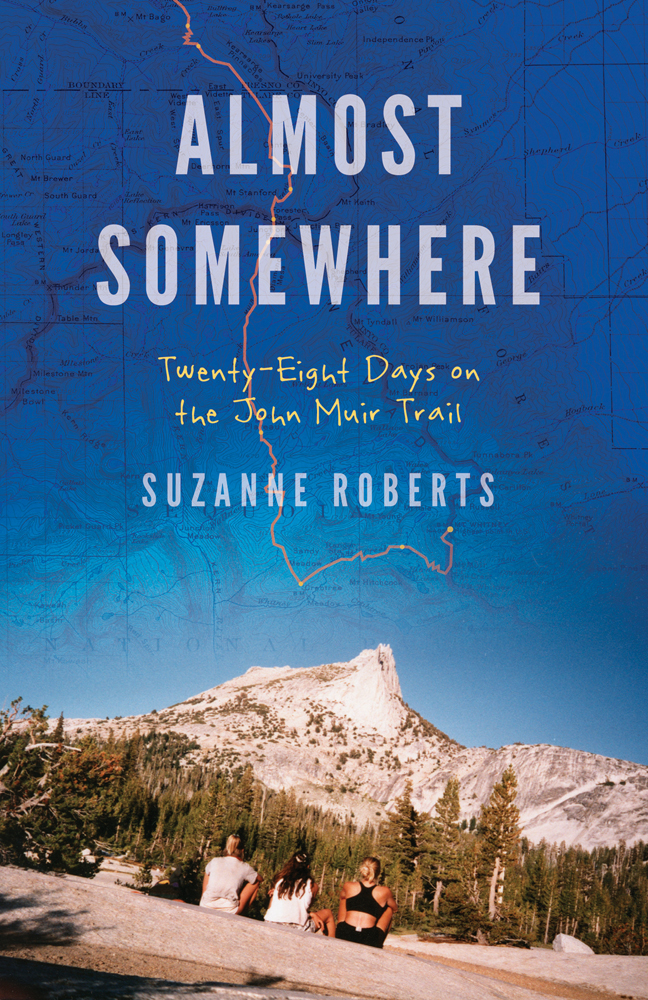

Sometimes Rejection Saves Us: Interview With 2012 National Outdoor Book Award Winner Suzanne Roberts

SR: I had two classes to take to finish up my degree when I returned from hiking the John Muir Trail in 1993, and in one of those classes, a women’s literature course, we were encouraged to write a creative piece for the final exam. I wrote an essay that became the seed for chapter 10, “The Ghost of Muir Pass.” In the literature classes I teach, I always end with a creative project, and I tell my students that story and say, “You never know, but you might be starting your book.” I certainly didn’t know I was starting a book at the time.

I needed first to find other women writing about nature, so I read Mary Austin, Isabella Bird, Annie Dillard, Pam Houston — any women writing about nature that I could get my hands on. I couldn’t write my own book, or enter the conversation, until I knew what the conversation was. I ended up with an MA in creative writing and a PhD in literature and the environment, and the intense study of books helped me find my own voice.

After writing a memoir that remains in the drawer, I started Almost Somewhere in earnest in 2003 while I was working on my PhD and writing poetry. I finished a draft in 2009 and started sending it out, even though it wasn’t ready. Sometimes rejection saves us. I reworked the book, and I sent it to nearly 100 agents, and the ones who expressed interest said it wasn’t commercial enough. The book then went though another major revision, and one very kind agent suggested I send it to a university press, and that is how I ended up at University of Nebraska Press. The book found its perfect home in the Outdoor Lives Series.

How does your process to writing nonfiction / memoir differ (if at all?) from writing poetry?

I am tempted to say that poetry is fun and prose is work, but that isn’t exactly true. Both are fun and both are work. My goal is to get the poetry into the prose, create the images within the narrative. I think the main difference in the writing, though, is that in memoir, I have to add the reflection layer, the part where I muse about what I think about the moment, whereas in poetry that is mostly left up to the reader. And that reflection or musing is hard because it has to be really honest to be good, and it’s difficult to get to that kind of truth. There’s a vulnerability in it. I also think that when you write memoir, you really have to block that voice that asks, “What are you writing that for? Do you really want everyone to know that about you?” In poetry, that voice is tempered by the fact that I can always say, “Oh that? I made that up.”

I’m very intrigued by the title of your latest book: Plotting Temporality. It’s a word I’ve used a lot when discussing writing, particularly about how we experience place (which is ‘bounded by temporality’) versus how we write about place (in which temporality can be played with, almost like post processing an image). What does it mean to “plot temporality”? Is that what the act of writing essentially does?

I think your question is a lot smarter than my answer will be. I found the title while reading literary criticism on Emily Dickinson. The critic said that Dickinson plots temporality, and that stuck with me, not just because it’s true of Dickinson’s poetry and writing poems in general, but because I liked the way that the words sounded together, which is essentially the way I write poems — playing with the ways in which words work together. As for what it means, I think that our lives plot temporality. We plot the course of our lives over time, charting out the seconds until they turn into minutes and the minutes until they solidify into an hour.

This morning a dear friend of mine lost her father, and she told me that one of the nuns who was there had said something about our “temporary lives.” Being a poet herself, that resonated with her, and as I answer this question, I can’t help but think of those two words together: temporary life. And I also can’t help but think about how writing is a way to capture our temporary lives, solidify the second or the moment so that it exists somewhere because the moment itself, well that’s gone except in our minds and memories and our art and literature. The obsessions of the book are time and death and sex and where those things intersect, so the title Plotting Temporality, even though it is hard to say, felt right to me.

What are you working on in El Salvador?

I don’t have anything in mind, aside from working on my Spanish and my tan. But I always keep a journal, and usually something comes up when I travel, so it will be a surprise.