I GREW UP in a predominantly Bengali neighbourhood in Calcutta. As a child I was actively encouraged to read.

As incentives for doing well on examinations or behaving nicely I was given a book. I did not choose the books–my parents chose them–but I remember holding the book in my hand, smelling the paper and running around the house in joy .

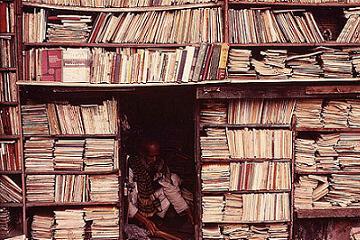

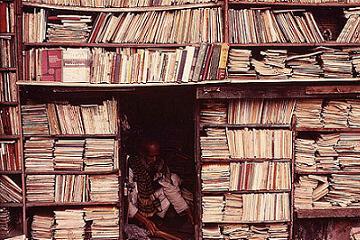

I delighted in the parar boier dokan. This was a musty, run-down bookstore, which sold second hand books alongside new arrivals. Around the corner of the bookstore was a muri (puffed rice) seller, who would sell muri in thongas– small bags made out of old newspapers. I’d spend hours trying to read the words on the thongas. By the time I was twelve, I was already writing my first “novel.”

It helped that I grew up bilingual. I was reading Bengali as well as English books. The Bengali Novel draws heavily from 19th century English writing in terms of structure, but reading Bengali literature, I read about people who had lives similar to mine, who probably lived on the same lanes that I do now, but inhabited my world in a different time.

Reading literature written in English taught me about people whose lives were not necessarily similar to mine, but I understood them because some of my struggles were mirrored in the stories.

I realize now however that my preliminary reading constructed a rather linear notion of books in my mind.

Reading the “Right” Way

Till the age of fourteen, I believed I was well read and that I was using my critical faculties to decipher fiction. Today, I believe that I was too unaware of histories and peoples to have come to rational, informed conclusions.

I read classics like Robinson Crusoe, for instance, but failed to consider the ill-treatment of Friday. I read Jane Eyre, but had somehow overlooked the plight of “the mad woman in the attic,” Bertha Mason.

Thoughts on the “legitimacy” of reading:

A. Books are like people. There can never be a “right” way or “wrong” way of reading a text.

In an ideal world, every individual should have the right / ability to express her or his opinion. But many people are unable to express themselves because they are subjugated by those who are in power. Just like people, there are books that create hierarchies in our minds- books that have, over the ages, purposely propagated eurocentric views of the world.

B. My political and geographical positions led me to think in a certain way.

After wading through rather difficult “postcolonial theory” in my first year of college, I came to the conclusion that I had unconsciously sided with Robinson Crusoe and had completely forgotten Man Friday. This notion was remedied when I read Foe by South African novelist J.M Coetzee.

Later, when I read Wuthering Heights, instead of looking at Heathcliff as a villain or glorifying him as “ The Byronic hero” (or falling in love with him! I was tempted to, but didn’t), my perception of Heathcliff was that of a common man, who dared to love someone “above him” in terms of class.

In my second year of college, I began to think seriously about notions of race, class and gender. What was legitimate writing and who made it legitimate?

As I was thinking about these questions, I chanced upon Black Venus by Angela Carter. Angela Carter writes about Jeanne Duval, the mistress of Charles Baudelaire. What really impressed me about Black Venus was that it brought Duval’s character to life.

I then read Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys and realized how Coetzee, Rhys and Carter were all trying to give a voice to the ignored and the forgotten by using classic literary texts as their starting points and reworking them.

C. Now, as a third year student of Literature, I feel like I am more aware of what I am reading.

Only recently, I began reading The Tempest for my course on Shakespeare and immediately sympathised with Caliban.

Conclusions:

1. Whenever reading, always be aware of dominant worldviews.

2. It is not a solution to be dismissive of writing that is considered “legitimate” but which causes tremendous discomfiture, but instead we must ask questions of every piece of legitimate writing: “why is it legitimate” and “who legitimised it?”

3. Without studying or being aware of the social, political, and historical context of the times / places that books were written, we risk creating a monolithic notion of books and characters in our minds.

Community Connection

How has your perception of books evolved? Let us know in the comments below.

For more of Reeti’s thoughts on books, please read 4 Classic Christmas Reads.