THERE’S AN old phrase Brian Eno supposedly said about the Velvet Underground. It goes something like “when the first Velvet Underground album came out, only about 1,000 people bought it, but every one of them formed a rock and roll band.”

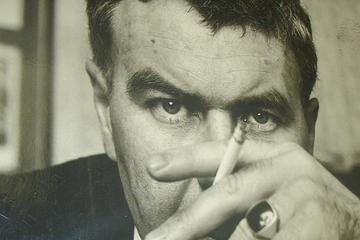

I’m not sure what the sales of Raymond Carver‘s first books were, but on a level of artistic influence you could apply a similar statement. People read him and want to become writers. Or they read him and it totally influences their style.