In the course of history, there’s been female writers, female bushwhackers, but also female bushwhacking writers. In other words, travel writers whose works have been invaluable for literature, sociology and anthropology. This article was originally written in French, and French is a grammatically gendered language. So when I typed “bushwhackers” and “writers” in the feminine gender, the spell-checker underlined those words with a string of dots as red as menstrual blood drops, one more reason for me to finish my article and click “Publish”. I won’t be exhaustive (if you want a more complete list, start here). I just chose for you 3 women whose writings and journeys have been important in the history of travel writing, and for History itself.

Dame Freya Stark (1893–1993)

Freya was damn unlucky as a kid. Her parents were struggling through an unhappy marriage, she fell ill every other day, and at the age of 13, an accident in a factory badly disfigured her. However, she had her very own way to escape. The Arabian Nights. And Dumas, too. She started to teach herself Latin, French, Farsi and Arabic.

As a grown-up, she can, at last, transform her daydreaming into proper adventure. She’s a volunteer nurse for the British Red Cross during WWI and she’s a student at the London School of Oriental and African Studies (yep, the still quite high-ranked SOAS). Finally in 1927, she boards a ship headed to Beirut. That’s when her career as a bushwhacking writer begins.

In just 4 years, she engages in three extremely dangerous treks through the Iranian West. She explores unmapped areas where no Westerner, male or female, ever set foot. By doing this, she discovers an area named the Valleys of the Assassins. For that, she receives in 1935 the Back Award from the Royal Geographical Society. Her travel journal describes her journey, stuck with unmotivated guides, falling ill, groping her way through places that are of a huge historical importance but that consistently fail to appear on Western maps. Her next trip leads her to Southern Arabia, where she writes many pieces for which she is again rewarded by the Royal Geographical Society. WWII leads her to Syria and the whole of Arabia, where she works for the Ministry of Information to incite local forces to fight for the Allies. She gets married when she’s 54 but leaves her husband 5 years later. She then sets to explore Turkey for years, and then Afghanistan while she’s almost 80. She was declared Dame Commander of the British Empire and died soon after her 100th birthday.

“Solitude, I reflected, is the one deep necessity of the human spirit to which adequate recognition is never given in our codes. It is looked upon as a discipline or penance, but hardly ever as the indispensable, pleasant ingredient it is to ordinary life, and from this want of recognition come half our domestic troubles.”

(Freya Stark, The Valleys of the Assassins and Other Persian Travels.)

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797)

Mary had a short life: she died aged 38 and yet her legacy is nothing short of impressive. She is one of the first feminists and her writing covers a large spectrum of topics, from the history of French Revolution to feministic pamphlets (A Vindication of the Rights of Woman), from children’s books to a travel journal, Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark.

The most baffling thing about her journey through Scandinavia is its motive: she goes there to please her French lover Gilbert Imlay, in search of a ship that is believed to contain a hidden treasure. She accepts this mission in the hope that her tumultuous relationship with Imlay will get better; she is sorely disappointed. Her travel journal is a fascinating bundle of landscape descriptions and personal thoughts on her doomed relationship and how it feels. However, the core value of her writing resides in her narrative style and declarations: her personal thoughts develop into reflections on the role of women in our societies, on the role of Reason in the complex interplay between people, society and nature. Her romantic approach of nature was endlessly praised by many male writers and has inspired names like Southey, Wordsworth or Coleridge.

After two unsuccessful love relationships, including that with Gilbert Imlay with whom she had a little girl, she marries philosopher William Godwin, one of the forefathers of the anarchist movement and a convinced admirer of her writing. Mary becomes pregnant with another daughter. But during delivery, her placenta breaks apart and becomes infected. Mary dies from septicemia after several days spent in agony. Years later, the little girl who was born that day will choose Mary Shelley as her pen name and write Frankenstein.

“England and America owe their liberty to commerce, which created a new species of power to undermine the feudal system. But let them beware of the consequences: the tyranny of wealth is still more galling and debasing than that of rank.”

(Mary Wollstonecraft, Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark.)

Rose de Freycinet (1794–1832)

Rose just didn’t want to leave her husband, and he didn’t want to leave her either. He was too afraid of never seeing her again. Those two were really, really in love. And who’d have ever thought that this could be? Rose was a middle-class girl, the daughter of a woman who ran a boarding school and of a father whose name nobody remembers. And yet, in 1813, Rose gets married way above her condition to an aristocrat named Louis de Freycinet — the navigator who ten years earlier had drawn the very first maps of a few Southern-Hemisphere coastlines.

In 1817, Monsieur Louis is to board a ship headed to South America, to be part of a scientific expedition sponsored by the French Navy and the Ministère de l’Intérieur. Spooked out of their wits by the stories of other navigators forced to abandon their wives due to multiple delays, imprisonment in a foreign land or horrific deaths, our two lovers have the most clever plan. As Rose simply cannot board the Uranie with her husband (women were strictly forbidden aboard such vessels), there’s only one thing they can do: dress Rose as a boy.

Hair cut, mariner’s outfit, secret ride to Toulon by night and without telling anyone in the family… Rose will pretend to be a boy right under the very nose of the Governor of Gibraltar and all the way to the Atlantic Ocean, where she can safely recover her gender identity.

That bold plan did not make Rose the first woman to circumnavigate the world, but it did make her the first woman to circumnavigate the world and write about it in a travel journal. This will all end in a shipwreck in the Falkland Islands; fortunately, both lovers and their team survive and make it back to France. However, in 1832, Paris goes through a massive cholera outbreak. With the help of a doctor she met aboard the Uranie, Rose manages with persistent care to save Louis’s life. Unfortunately, she falls ill as well and dies some time after.

I was forced to walk by all the officers that stood on the deck. Some asked who I was: our friend told them that I was his son, who indeed was roughly my size.

(Rose de Freycinet, in her travel journal; personal translation)

The journal, originally titled “Campagne de l’Uranie” (Campaign of the Uranie), is still as of today of an invaluable importance for anthropological studies. The original text was acquired by the State Library of New South Wales of Sydney in 2015. This late acquisition actually did Rose justice, by restoring documents that had been quite unfairly modified.

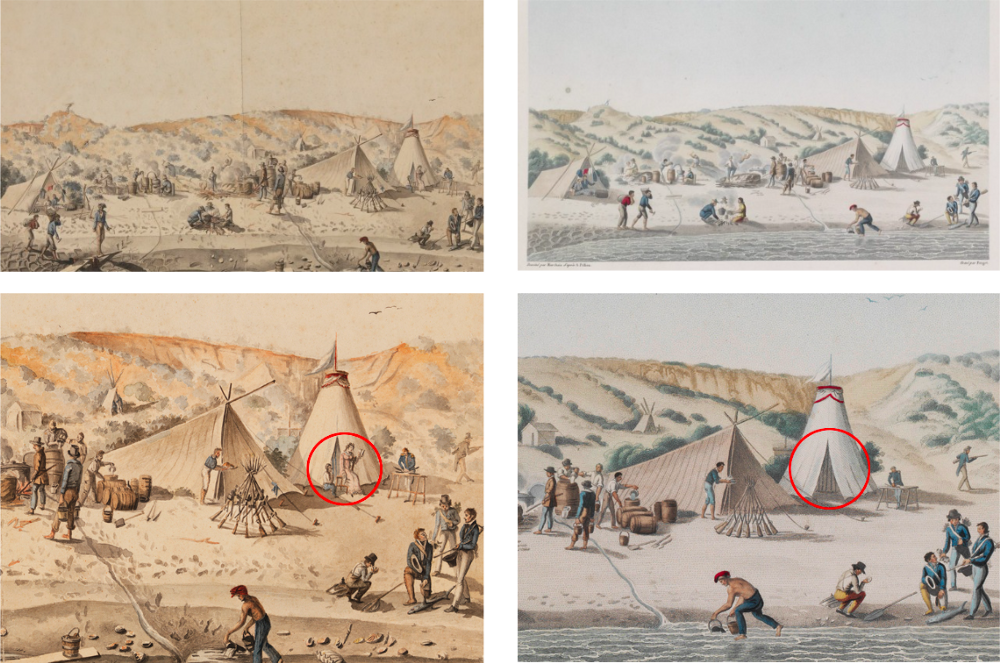

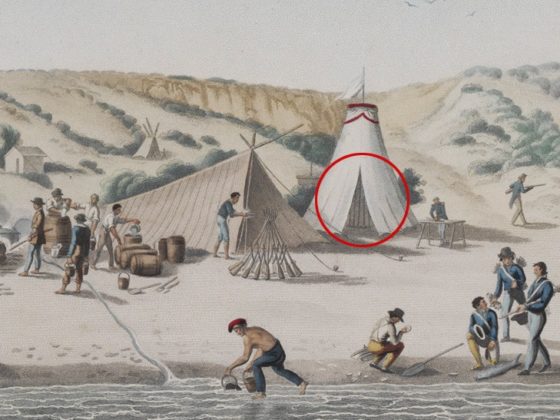

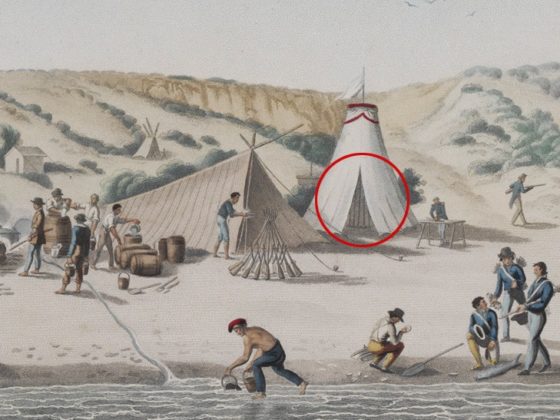

Louis had taken a huge legal risk when he let his wife aboard, dressed her as a boy, made room for her to have her private apartments, changed the Navy’s rules of hygiene and food quality for her safety. Rumors went wild as soon as the vessel left the harbour. Eventually, the couple was not punished by the authorities; but the authorities did everything in their power to erase that embarrassing event from the records. Louis’s official report makes no mention of his wife being present aboard. The Navy’s officials went as far as editing Jacques Arago’s paintings (Arago was the artist in charge of illustrations during the whole expedition). To the left, Arago’s original drawing with Rose busy with writing her journal; to the right, the official edited drawing — without Rose (source):

Not all was lost for Rose though. An atoll in the American Samoa wears her name (the Rose Atoll) ever since Louis and her passed by it in 1819. As for her travel journal, science could not enjoy and learn from it until much later. When Rose died, Louis gathered every page and letter that formed her original journal and had it all copied in one single volume. That volume is the text that we can enjoy reading today. It was published for the first time… in 1927.

I really wanted to tell you Rose’s tale in this short selection. And FYI, Rose was not the first woman to circumnavigate the world for a very simple reason: another Frenchwoman had accomplished that deed in 1760. Her name was Jeanne Barret. She had boarded a ship with her partner, Botanist Philibert Commerson… under the name of Jean Barret, dressed as a valet.

This article originally appeared on Medium and is republished here with permission.