Reaching what is left of the Aral Sea will take a long time no matter where you choose to depart from. Located in a remote corner of Central Asia between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, the lake that was once the fourth largest in the world has been receding for the past six decades, with disastrous consequences for the communities relying on its waters. The dark pools staining the vast expanse of arid flatlands that can be seen today on a map represent a fraction of what the Aral Sea used to be. Registered in UNESCO’s Memory of the World archives, the ecological tragedy that damaged the region was caused by a force that turned out to be much fiercer than global warming — the Soviet Union’s agricultural policies.

The Aral Sea Is the Ecological Disaster That You've Probably Never Heard Of

What happened to the Aral Sea

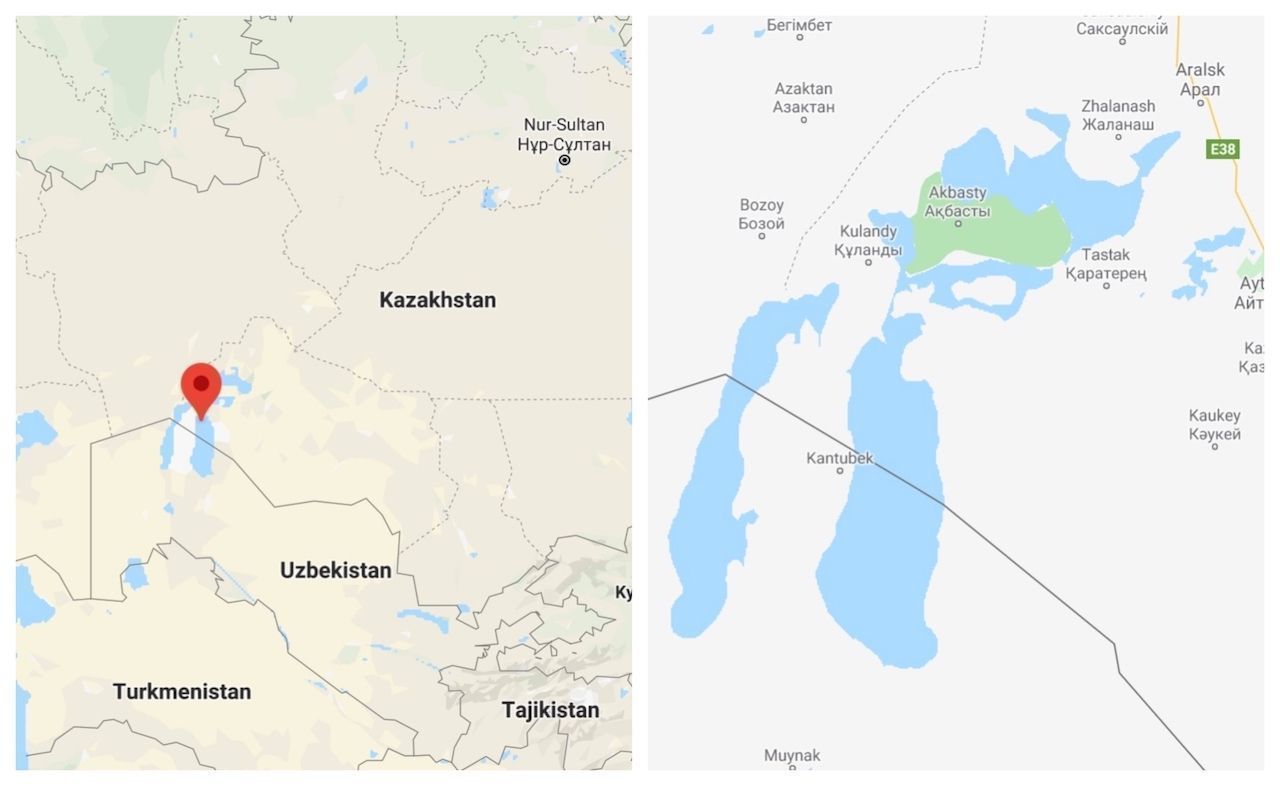

Photo: Google Maps

Until the 1960s, the Aral Sea covered an area of 26,000 square miles surrounded by arid steppes, which provided the USSR with tens of thousands of jobs and over 15 percent of its fish catch. This, however, was not enough for the Soviet government, which in the second half of the 20th century, decided to convert the dry region into one of the world’s largest cotton plantations.

The Aral Sea’s water was supplied by two of the major rivers in Central Asia, the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya. The new plans to boost Soviet agriculture established that, rather than feeding the lake, the water sources should be diverted to form the irrigation system necessary to sustain the growing cotton industry. Under Khrushchev’s rule, engineers built 20,000 miles of canals, 45 dams, and more than 80 reservoirs to redirect the water to irrigate the fields.

Photo: Angelo Zinna

Uzbekistan did become one of the world’s top cotton-growing regions, but while from an economic perspective the strategy was successful, the cost for the environment was unprecedented.

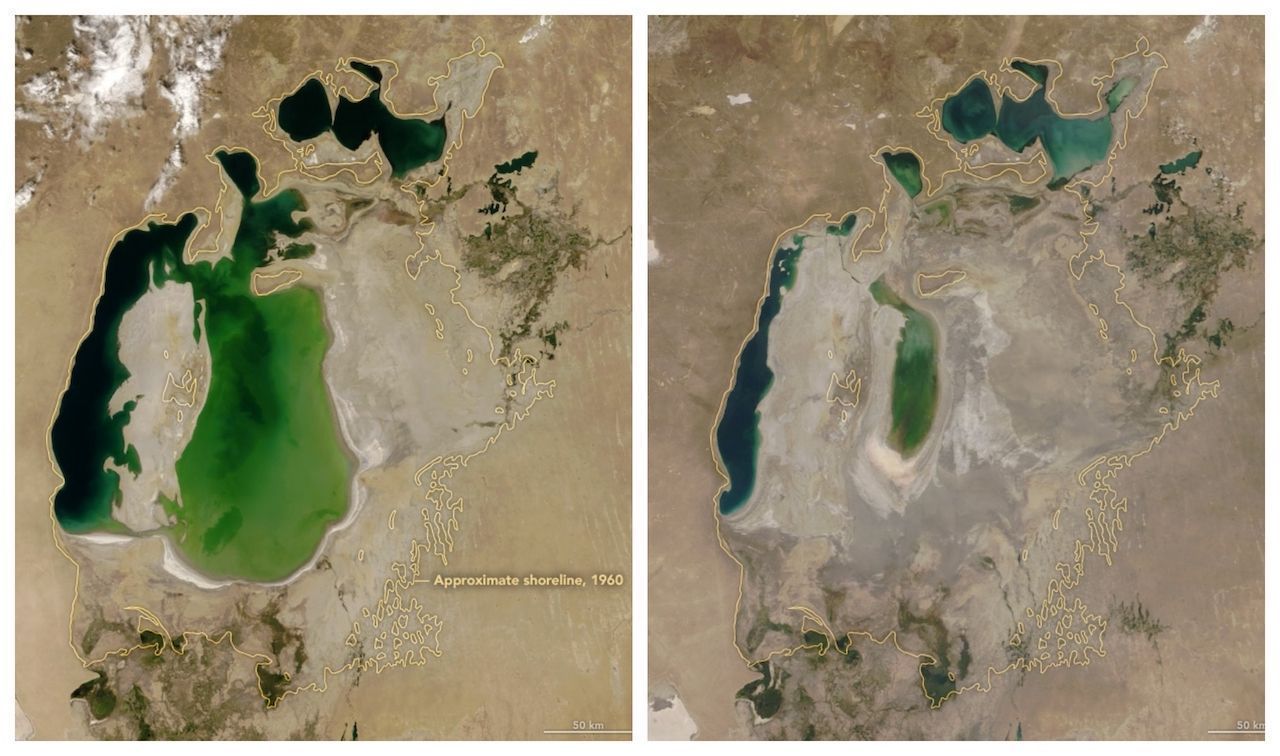

With rainfall composing only one-fifth of the lake’s water supply, the Aral Sea began shrinking rapidly from the 1960s. Over the course of four decades, the basin decreased to a tenth of its original size, ultimately almost splitting into a northern section on the Kazakh side and a southern section on the Uzbek side. In the summer of 2014, a satellite image from NASA’s Terra Satellite showed that, for the first time in modern history, the eastern lobe of the Southern Aral Sea had completely dried up.

Left, the Aral sea in 2000, with its 1960 borders drawn in yellow. Right, the Aral sea in 2018. Photo by NASA Earth Observatory.

The impact of this human-caused ecological disaster continues to be felt by the local communities that try to survive in fragile conditions. The fishing village of Moynak, south of the Aral Sea, once a town of over 30,000 people, has witnessed over half of its population leave as the lakeshore shrunk further and further away. The disappearance of the Aral Sea, however, didn’t only affect job security. With water being substituted by a vast expanse of barren soil, the climate is changing, making rainfall even scarcer. Sand and salt are now transported by the wind together with dangerous chemical substances used to fertilize the cotton plantations, contaminating the whole region.

The chemical weapon test ground: Vozrozhdeniya Island

Until 1948, Vozrozhdeniya was an anonymous patch of soil among the turquoise waters of the Aral Sea. The 75-square-mile island used as a launching base for local fishermen acquired a different purpose as the Soviet government decided to transform this isolated corner of the planet into a testing ground for some of the deadliest chemical weapons in existence.

Unknown in the Western world, Vozrozhdeniya Island became the host of the top-secret Aralsk-7 project. From the end of WWII to the fall of the Union, this remote territory remained a hidden site where poisons and viruses were converted into weapons. According to the BBC, anthrax was cultivated in large fermenting vats next to smallpox, bubonic plague “and exotic diseases including tularemia, brucellosis, and typhus.”

With the fall of the Soviet Union, the goings-on on Vozrozhdeniya gradually emerged from the shadows, and while a joint American-Uzbek operation attempted to clean up the place, reports on the safety status vary widely. What’s more, the island is no longer an island — with the evaporation of the Aral Sea, Vozrozhdeniya has become part of Uzbekistan’s Karakalpakstan desert, and the contaminated soil is now connected to the rest of Uzbekistan’s territory.

Located 225 miles from Moynak, Vozrozhdeniya remains far from accessible. Visitors with an inkling for dark places are slowly reaching the toxic wasteland, however, and it is possible that the area will open up to tourism in the near future.

Attempts to bring the Aral Sea back

Photo: Angelo Zinna

The agricultural policies put in place by the Soviet Union continued unchanged after 1991. Under the presidency of Islam Karimov, who took power in Uzbekistan after independence and governed until his death in 2016, the cotton industry stayed within the control of the state, which pushed to keep its status as one of the leading producers without considering either the human or environmental cost. The production of water-intensive cotton has depleted much of the Uzbek territory of its topsoil, causing land to dry up as a result of the unsustainable monoculture.

But hope survives in the Northern Aral Sea, where efforts to save what is left of the basin have shown positive results in recent years. As part of an $86-million project funded by the World Bank, Kazakhstan has erected the Kokaral dam, an eight-mile-long dike completed in 2005 which has led to an incredible 11-foot increase in water levels in just seven months. The return of water in the lake has meant a return of fish, with catches growing after years of poor gains. Optimism is back in the town of Aralsk as the northern section of the Aral is being saved.

Visiting the Aral Sea

From Almaty, Kazakhstan, a train journey of at least 20 hours is necessary to get to the sleepy fishing village of Aralsk, the northern access point to the Aral Sea. Aralsk can also be reached by train from Aktau in the west. From the village located, you will have to join a tour to reach the shoreline, the sea bed, or any of the villages that once surrounded the lake. The local expert is Serik Dyussenbayev who has collaborated with the NGO Aral Tenizi, which has been providing local fishermen and their families with social and financial support while helping in the re-establishment of the sea.

A standard 4WD trip across the sea covers approximately 180 miles on dirt road, crossing the seabed among herds of camels, rusting fishing boats, and semi-abandoned villages. The tiny settlement of Akespe, where only nine families live today, emerges among the sand dunes of this environment. A hot spring sees some local visitors coming for its thermal muds. Other than that, encounters with other humans should not be expected — the area is just one huge expanse of emptiness surveyed by eagles on the hunt for prey hiding among the low vegetation.

Photo: Angelo Zinna

From the Uzbek capital of Tashkent, travel time is not much shorter, with Moynak, one of the few settlements left in the region, over 800 miles away.

Compared to the Kazakh route, the Uzbek part of the Aral Sea is a lot more popular among visitors. The main attraction on this side of the border is the “ship cemetery,” a photogenic collection of vessels standing tall in the middle of the steppe, reminding tourists where the water once was. While on the Kazakh side most abandoned ships have been dismantled, the town of Moynak, in Uzbekistan, relies heavily on tourism and is, therefore, protecting these impressive sights. Overnight tours can be organized from Khiva and Nukus.