Paul Manser is no stranger to rolling with the punches. As a travel writer based in Melbourne, Manser has been able to see the world and report back for newspapers and magazines in Australia and elsewhere. His work, as with most professional travel writing, is polished and edited to focus on the style that travel publications like to promote: clean, safe adventures that don’t step over the line.

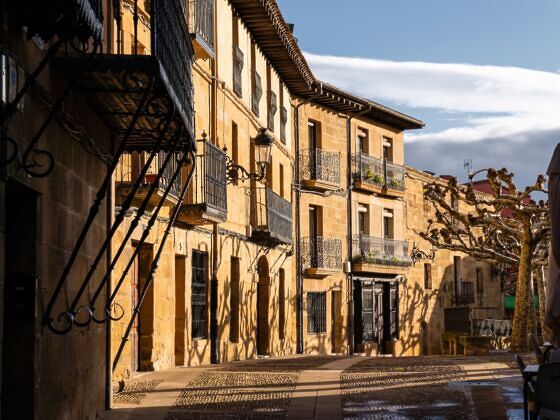

In Basque Country, Food Societies Are the Secret to Understanding the Culture

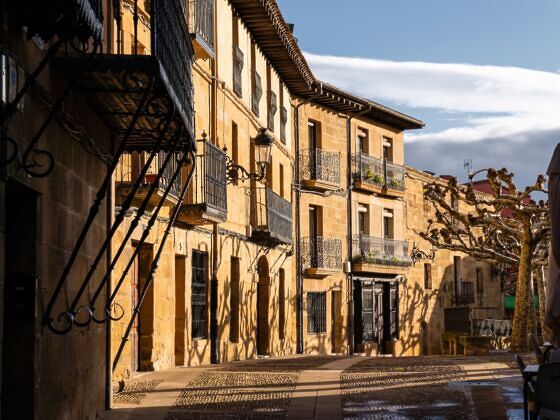

His actual travels can be anything but that. Manser collected the stories that aren’t a fit for glossy travel magazines and put them in a book, Life Plans on Dive Bar Napkins (Hardie Grant). It’s a look into the real (often gritty, sometimes dangerous, and occasionally ridiculous) life of a well-traveled writer.

Photo: Life Plans on Dive Bar Napkins, Hardie Grant

“Things rarely go exactly to plan when traveling, which is why I like to think ahead as little as possible and embrace chaos like it’s a long-lost sibling,” Manser says over email. “There’s no faster way to ruin a trip than by scheduling every minute like you’re running a corporate board meeting. Travel isn’t a PowerPoint presentation — it’s a fever dream, and for me, the best parts are when everything goes wrong.”

The book features accounts like the time he was kidnapped in a taxi in Mexico, crashed a dog sled in the Arctic Circle, and took an impromptu (and booze-filled) trip to see the running of the bulls in Spain. It’s a testament to being a resilient traveler and all of the experiences that can only be had by pushing limits.

“My mindset on the road is equal parts ‘yes-man’ and ‘what’s the worst that could happen?’” Manser says. “I’ll drink the questionable cocktail, take the wrong turn, and trust the food truck guy’s sketchy recommendation for a dive bar that may or may not double as a front for a black-market organ operation.”

Photo: Paul Manser

Manser openly stated in a press release that Life Plans on Dive Bar Napkins could be seen as “an unnecessary act of self-indulgence by an egotist who shirks life’s responsibilities, drinks too much, and thinks too little.” He also adds the description would “probably be right,” but there’s a good case to be made for the unvarnished side. After all, the best stories are the ones you don’t plan for.

“So sure, book your flight and maybe your first night’s stay so you don’t end up sleeping under a bridge in a foreign country (unless that’s your thing, no judgment),” Manser says. “But after that, let it unravel. Think of every mishap as a plot twist, not a problem. Missed connections? A gift from the travel gods to explore the place where you’re stuck. Food poisoning? The ultimate character-building experience. That miserable bus ride through rural nowhere? That’s where the stories are born.”

Here, an excerpt from Life Plans on Dive Bar Napkins about finding culture through culinary societies in Basque Country.

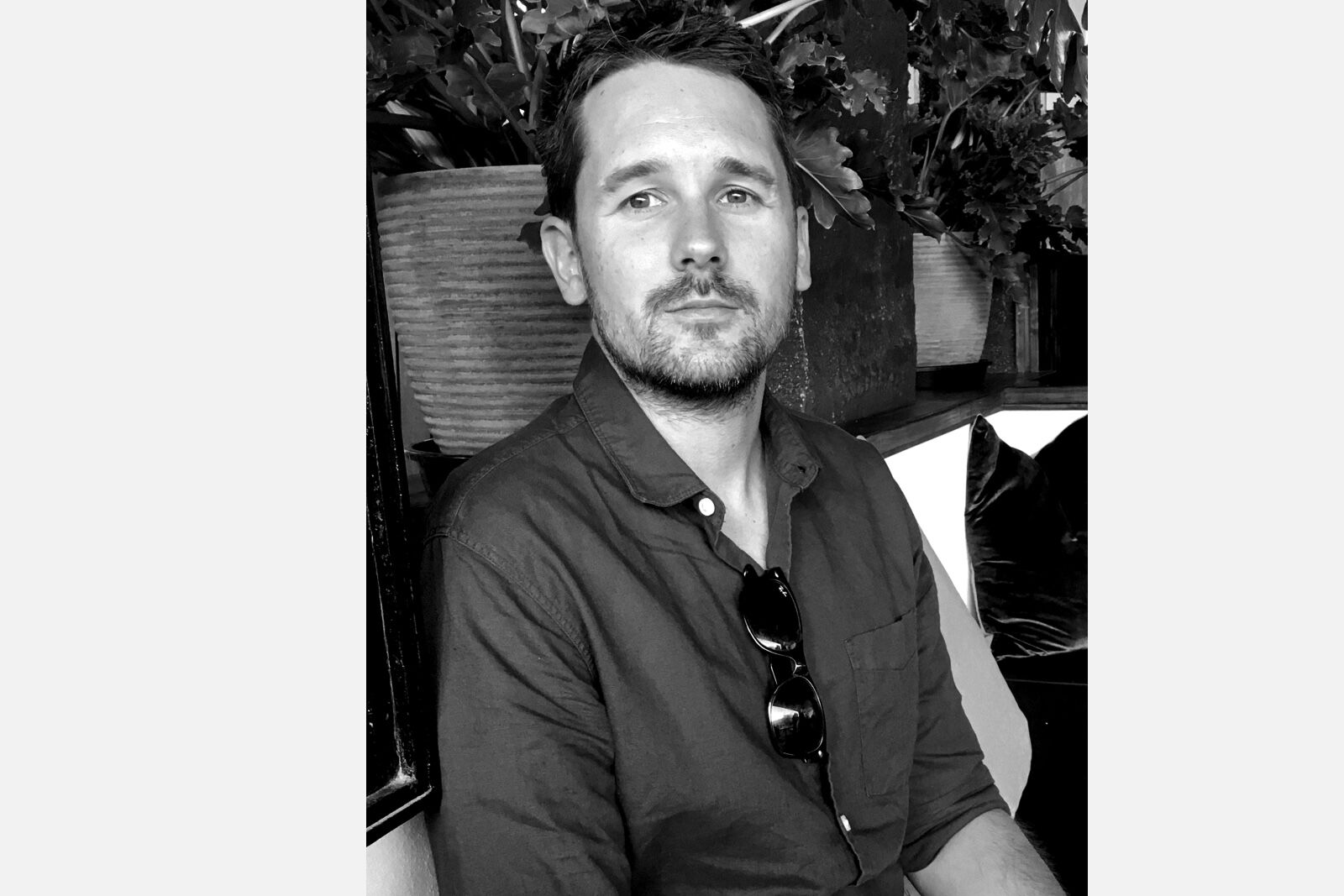

The Society

Photo: Paul Manser

Sunset steals into the kitchen. It has been raining again. The horizon is smudged grey and orange as if someone has smeared a dirty thumb along where land ends and the sky should begin. Ramon weighs a bulb of garlic in one hand. He pushes away a half glass of cider. An old digital clock flashes neon red from across the room.

‘They’re always late,’ Ramon sighs.

We walk outside. The main road steams as an overladen truck, pregnant with dairy for the market, passes at speed.

A sign above the bus stop indicates that we are outside of Elgoibar, in the Basque Country of northern Spain. The town pays homage to the functionality of stone and concrete. Stark, drab, rectangular apartment blocks jut out of the ground. The shades of residential grey are punctuated by painted maps hanging across apartment balconies. The maps are an outline of Basque Country, emblazoned with large red arrows.

I point out the maps and ask Ramon ‘What’s all this about?’

In his deep, commanding voice, Ramon says, ‘When people were arrested for being members of Basque’s separatist group ETA, or suspected of carrying out activities in its support, they were sent to jails in the Spanish colonies in Africa.

‘The maps with the red arrows are a message: “Bring our sons, daughters, brothers and sisters home. Jail them if they are guilty, but let their families visit… don’t isolate them a world away”.’

It is said that the Basque language is the oldest in Western Europe, and that their people are the oldest permanent residents of the continent. The pocket of northern Spain and southern France that they occupy is cruel in its beauty. It leaves you wondering how you got cheated out of such natural scenery when you were growing up.

The thick green forests, untouched by water restrictions, soaring mountains and isolated farmhouses of Basque Country lampoon the sprawling suburbia and flat, brown expanses of my youth on the peripheries of Melbourne.

Ramon is back in the kitchen with a knife in his hand. Flashes of silver dance across the blade under a naked light bulb. It cuts smoothly into the flesh of a tuna.

Photo: Paul Manser

‘This dish is better prepared one day in advance,’ Ramon says.

I ask, ‘Is it a traditional Spanish recipe?’

Ramon puts the knife down. He tells me to be careful.

‘The Basques are proud. Don’t call their food Spanish.’

Ramon picks up a bruised tomato and squeezes until it explodes over a pot of half-cooked onions. He says, ‘Last century the Basques were brutally oppressed by the Spanish dictator, General Franco. The Basque culture, our language and our way of life were to be stamped out.’

Ramon’s family only learned Basque through being taught by older relatives and family friends in isolated farmhouses. If they were caught, those passing on their native tongue would have had a four-walled cell from which to contemplate their passion for education.

Thick chunks of tuna fall into a crimson sea of softened red peppers.

Ramon takes care to wipe the bench clean of splash marks, like he is polishing a car for his daughter’s wedding. There is a mound of rough, earthy potatoes waiting to be guillotined on a wooden chopping board and it’s clear that there’s more work to be done.

Perhaps more than anywhere else in Europe, Basques are obsessed with food. Since the 1870s, Basque men have been secretly gathering in small member-based groups and cooking together in communal kitchens called txokos, or societies.

Photo: Paul Manser

There’s a knock at the front door. The echo of bare knuckles against stained wood announces the arrival of Ramon’s family. He rests a worn wooden spoon on a pillow of soft-boiled potatoes. Voices come running into the room, followed by the people they belong to. A tsunami of chatter; the six people fill the large room. The kitchen is quickly occupied by shaved cured hams, local hard cheese and juicy peaches.

Ramon kisses everyone twice, then waves them away. A growing mist engulfs the kitchen as a pot comes to boil. Ramon turns the heat down.

Ramon clears his throat. ‘During the Franco years, txokos filled the stomachs of the Basque people and became venues of defiance,’ he explains. ‘They were one of the only places where Basques could legally meet without state control. A place where they could speak Basque, sing Basque and be Basque.’

Ramon’s wife is in the kitchen telling a story about a cousin who can’t find work. It seems to be a story told many times in these parts. More than half of people under the age of 35 are out of work.

I ask Ramon, ‘What is this doing to the country?’

Ramon doesn’t say a thing. He just points a twisted finger, scarred by the cuts and callouses of someone who relies on his hands for a living, to his temple and twists like he is opening a new bottle of wine.

The family binds around a thick wooden table. Bread is ripped from a long cob and placed beside shallow bowls. Ramon struggles under the weight of a giant pot full of marmitako, the fish stew he was preparing earlier.

Photo: Paul Manser

I say to Ramon, ‘I’ve hardly seen a fast-food chain since I came to Basque Country.’ He smiles, and deep lines carve into his cheeks. ‘They rarely work. People here like to know who they are buying their food from, where it comes from,’ Ramon says.

Ramon arches his neck back so that his eyes follow the cracks in the plaster roof. His wife wraps an arm around his waist. The table explodes in laughter as the grandmother’s glasses fog from the steam of the freshly served marmitako.

Excerpted with permission from Life Plans on Dive Bar Napkins (Hardie Grant) by Paul Manser. The book is available now wherever fine books are sold, as well as online at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.