Given its diameter of over 100,000 light-years across and the more than 100 billion stars calling it home, it’s easy to be overwhelmed by the vastness of the Milky Way. Humanity’s knowledge of our galaxy’s formation is as ever-evolving as the galaxy itself, but we do know one thing for sure — it’s a hell of a lot of fun to look up at the sky on a clear night.

These Constellations Are in Full Force This Spring. Here's When to Watch Them.

Throwing a towel down in the yard and gazing upward is one of the few out-of-the-house things we can do to quell our wanderlust in the depths of the coronavirus pandemic, particularly while still following the principles of social distancing (assuming your yard or the local park has enough space to put six feet between you and any passersby).

There are 88 marked constellations viewable at different points of the year, some far easier to identify than others. The following are the easiest to view during spring in the Northern Hemisphere — and you should be able to identify each with nothing more than a notebook, a pen, and one clear night of searching. If nothing else, laying in the grass and staring at these constellations is a reminder that there’s more out there than our currently isolated state.

Why constellations are brighter at certain times

Constellations move, ever so slowly, to the west as each year progresses. As the earth orbits the sun. You’re looking into space from a different direction at different points throughout the year, while the stars themselves remain in their place. Therefore, what you see in spring is different than those constellations viewable at other points throughout the year.

How to locate a specific constellation

Viewing directions for constellations tend to be extremely confusing to most who aren’t astronomers. This is because those directions were written by said astronomers, the few who understand the terminology used in their field, which reads to the rest of us like a science textbook that’s three grades too advanced. Before heading out to stare at the stars, understand these common terms and wayfinding directions used in constellation mapping.

Square degrees: The easiest way to see the curvature of the earth is to look at the sky on a clear night. The star pattern seems to rise from one direction, crest, and then descend in the other, no matter which way you’re standing. This is the easiest way to understand square degrees, which refers to specific parts within a sphere, as opposed to degrees within a flat circle (as you might measure with a protractor). Square degrees note the exact amount of space a constellation occupies in the spherical sky, similar to how you might describe the size of your home in square feet or square meters. They are written as square degrees or X deg2.

Latitude: In astronomy, latitude is the same as if looking at a map and is used to note the latitudes between which a certain constellation is visible. For example, if a constellation is noted as being visible between +90° and -20°, that means that you’ll be able to see it on a clear night as long as you are located between those two latitudes.

Tips for optimized stargazing

Photo: Maria_Janus/Shutterstock

- Light is not your friend. There’s a reason why you’ve never been invited to a stargazing party at that fancy rooftop bar in downtown Manhattan — it’s a lot harder to see stars when you’re surrounded by light pollution. Finding constellations is a lot like playing connect the dots, and the darker the area around you, the more of those dots you’ll actually be able to see.

- But binoculars and telescopes are. Once you’ve identified a constellation, zoom in on it with a pair of binoculars or a household telescope to really get the image of what it’s supposed to resemble.

- Sketch each constellation as you identify it. Much as writing something down helps you remember it later, sketching a constellation will help you identify it quicker the next time.

- Read up on the mythology behind the constellations. Many constellations, including Ursa Major and others viewable this spring, are noted in such literary heavyweights as The Bible and Homer’s The Odyssey and are also prominent throughout Greek and Roman mythology. To learn about their backstory, The Book of Constellations by Robin Kerrod is a great place to start. Online, Constellation Guide offers overviews of the mythology behind each constellation.

- Have a Bloody Mary. Lycopene, found in abundance in tomato juice, is known to ward off night blindness. It’s worth a shot, at least.

Brightest constellations in the Northern Hemisphere this spring

Editor’s note: Photos of constellations are artistic renderings and not a realistic depiction of the night sky.

Boötes

Photo: Pike-28/Shutterstock

Boötes is located in the third quadrant of the Northern Hemisphere and takes up 907 square degrees. The name itself is ancient Greek for “the ox herder,” and Space.com notes that the constellations tends to resemble itself as herding of The Big Dipper, though you may find that to be a bit of a stretch. Either way, Boötes is easy to spot because it contains the third-brightest star in the sky, known as Arcturus, and is visible from spring through summer.

Leo

Photo: Pike-28/Shutterstock

Leo the Lion occupies 947 square degrees and of all spring constellations is the one that most easily resembles what it’s supposed to look like. It’s located adjacent to Cancer, Hydra, and Ursa Major, making it even easier to spot if you’ve already located one of the others. Look north of Hydra for Leo’s shining star, Regulus, which marks the front paw of the lion, and then look north to connect the dots from there. You can see it between the latitudes of +90° and -65°.

Cancer

Photo: Pike-28/Shutterstock

Cancer loosely resembles a crab, as its name means in Latin, high in the northern sky. It’s among the smaller of spring’s major constellations at just 506 square degrees, and it dims as the spring moves on — its best viewing season, according to Space.com, is March between +90° and -60° in latitude. To find it, look directly east of Leo to a rather dense-looking collection of stars centered around two brighter stars — Asellus Borealis (northern) and Asellus Australis (southern) — that are almost directly on top of one another.

Hydra

Photo: Pike-28/Shutterstock

Despite being the largest constellation, it’s tough to make out Hydra the first time because this constellation is a long, meandering line of stars stretching across 1,303 square degrees between +54° and -83° in latitude. Its name makes perfect sense — meaning “the watersnake” in ancient Greek — as it slithers its way through the night sky south of Virgo and southwest of Cancer. Hydra’s head is just below Cancer, in fact, as if the watersnake were about to conclude its dinner hunt on the neighboring star formation but never quite got around to making the final pounce.

Virgo

Photo: Pike-28/Shutterstock

Virgo looks like a man lying on his back, in between and just below Boötes and Leo. Its brightest star, Spica, serves as the left hand at the bottom of the constellation, with Porrima to the northwest being the shoulder and the right hand extending northward to the star Vindemiatrix. Look east to see the three stars that form the border of Virgo’s head, and west to see the torso and legs. Virgo is the second-largest constellation, occupying 1,295 square degrees, and is visible further south than the other spring leaders — you’ll see it between the latitudes of +80° and -80°.

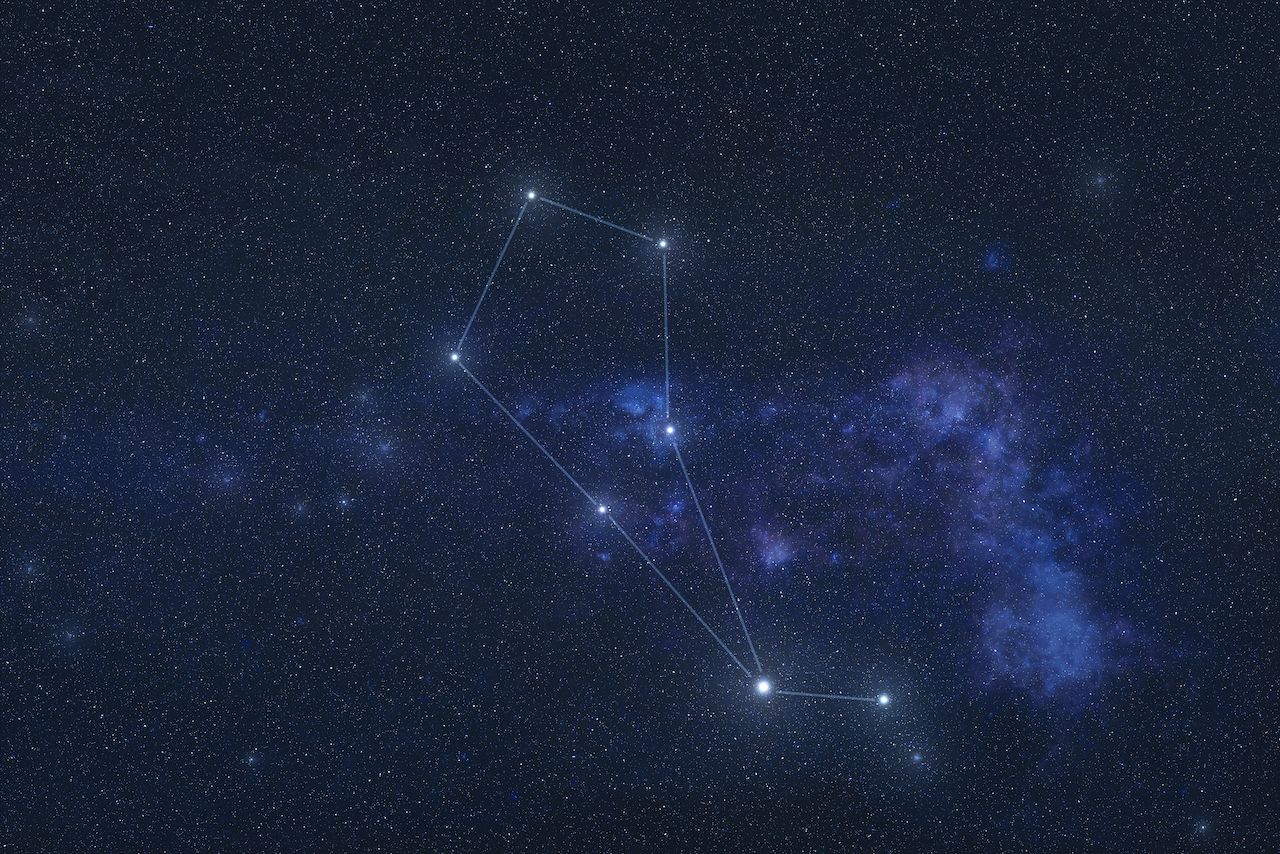

Ursa Major

Photo: Pike-28/Shutterstock

“The Great Bear,” as Ursa Major means in Latin, contains a number of major stars including Dubhe along the bear’s upper back, Muscida to the east at the top of its head, and Alkaid representing the tip of its tail on the far west, just east of the Boötes constellation. Ursa Major is 1,280 square degrees in size and viewable between the latitudes +90° and -30°. The Owl Nebula lies within it, and if you were to visualize the entire body of the bear, so does The Big Dipper.