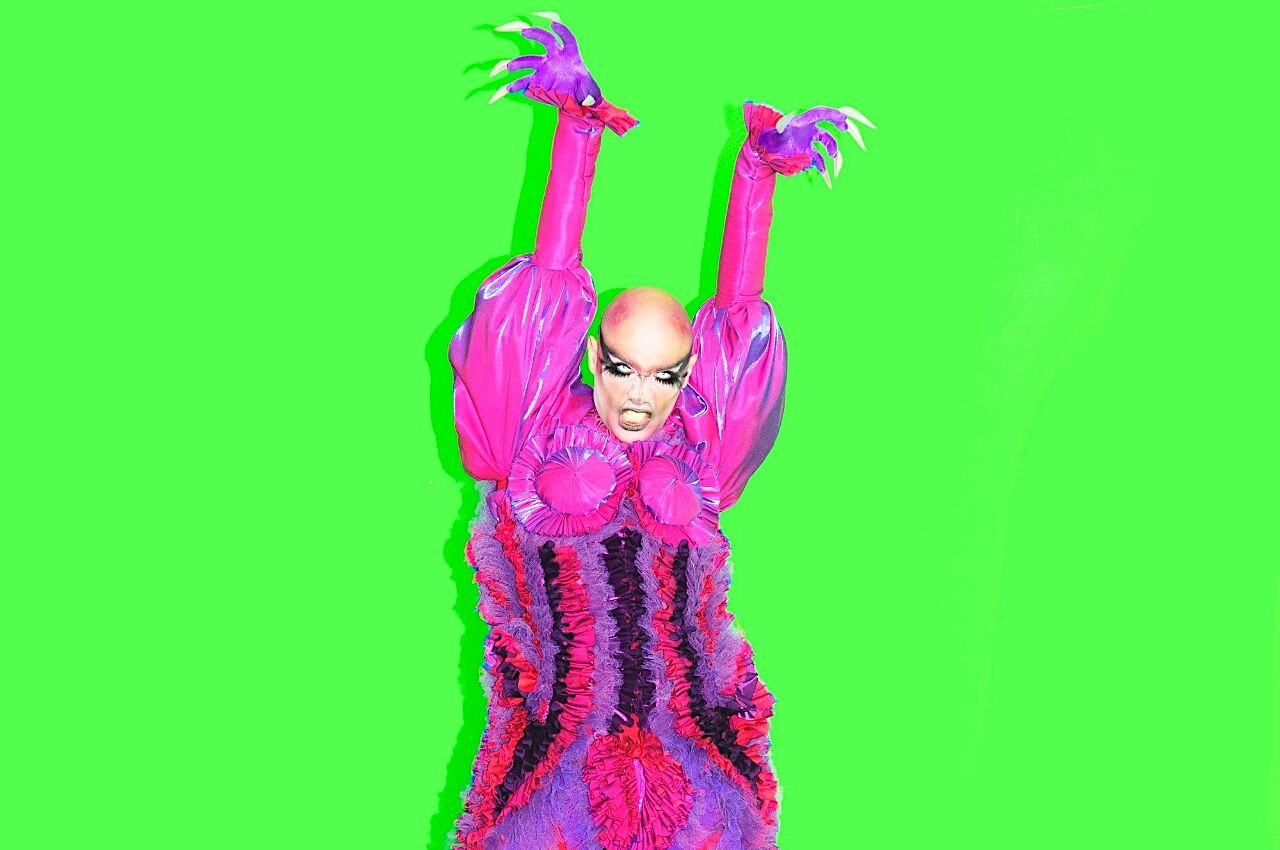

The first time Onyx Godwin Ogaga saw a drag queen perform, they were amazed. “I was surprised that [drag] even existed,” says the 23-year-old nonbinary drag artist from Lekki, Nigeria.

It was 2014 — five years after RuPaul’s Drag Race began pitting queens against one another in a battle royale to become America’s Next Drag Superstar. The same year, Nigeria signed the Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Bill into law.