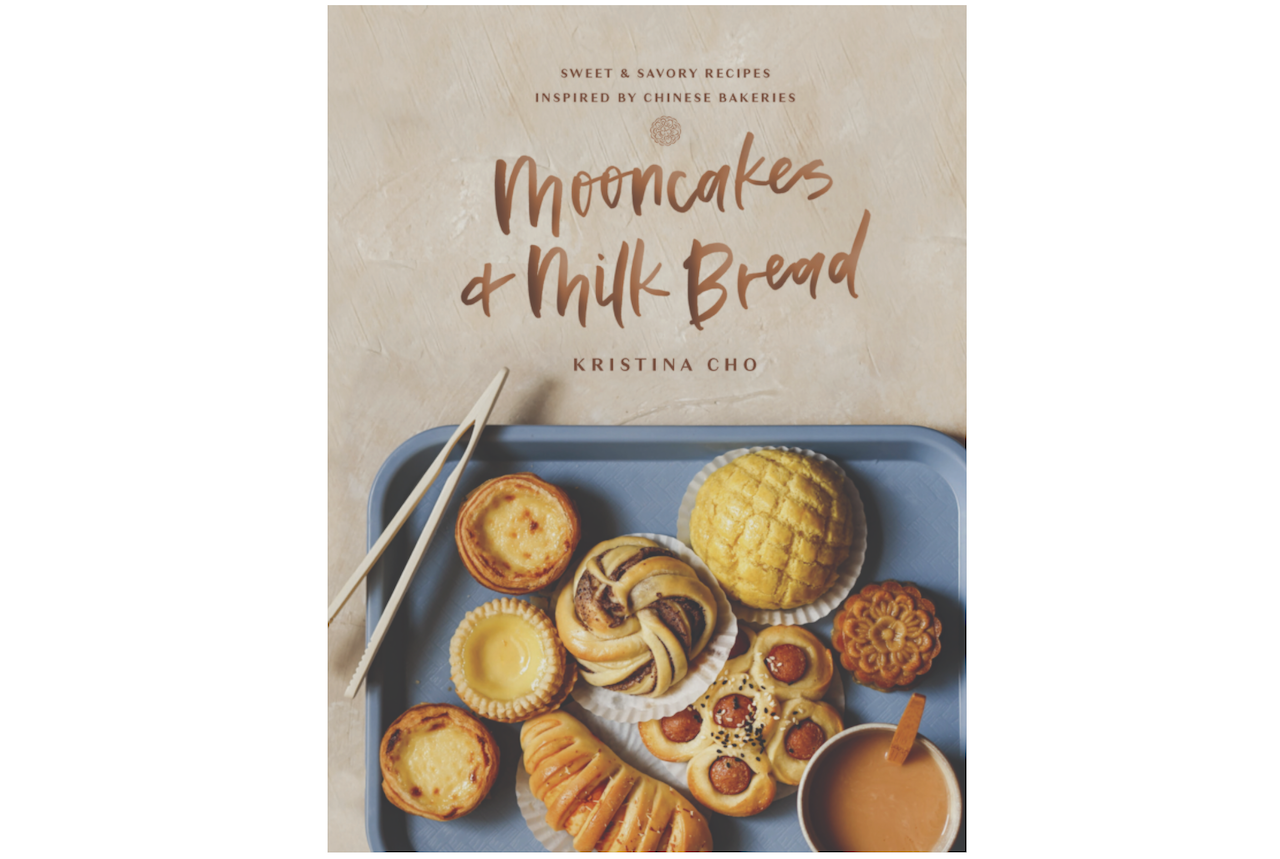

In a funny way, America’s quintessential cookie, the chocolate chip, inspired Kristina Cho to write a cookbook about Chinese baked goods. “There’s a billion recipes for chocolate chip cookies out there,” she tells me over the phone, explaining the motivation behind Mooncakes and Milk Bread: Sweet and Savory Recipes Inspired by Chinese Bakeries. “But you’d be hard-pressed to find things like a mooncake or red bean swirl bun.”

This New Cookbook Spotlights China’s Underappreciated Baking Traditions

Yet Cho, author of the popular food blog Eat Cho Food, knew the demand for these foods was there. When she first started posting recipes for Chinese-inspired buns a few years ago, the response was overwhelmingly positive. Readers raved about her tea-infused shortbread and hot dog flower buns, which Cho describes as “pure childhood for me and a lot of people.” Many commenters thanked her for reconnecting them with the foods they grew up eating.

Nostalgia was a driving force behind the cookbook. Growing up in Cleveland, Ohio, Cho remembers thumbing through tins of Cantonese-style mooncakes at her local Chinese grocery in search of the most interesting flavors, particularly around the Mid-Autumn Festival, a holiday honoring the fall harvest. Dense and round, symbolizing togetherness, mooncakes are a festival staple that’s meant to be cut into wedges and shared with family. Chinese hot dog buns, on the other hand, always make Cho think of Hong Kong and her frequent visits there as a child.

The sentimentality that her recipes evoke also resonates with readers who are unfamiliar with traditional Chinese baked goods. Those who’ve never had a hot dog flower bun probably have memories of eating pigs in a blanket, Cho posits, or American-style hot dogs. “As they look through the cookbook, [readers] will start to learn that there are a lot more similarities between Chinese baking and Western baking than there are differences,” she says.

Colonialism explains many of these similarities. Beyond baked goods like Chinese-style egg tarts, which, Cho remarks, look like something you’d see on the Great British Baking Show, the very concept of the Chinese bakery was influenced by imperialism. What’s now seen as a traditional Chinese bakery in the West was popularized in Hong Kong in the mid-20th century, roughly 100 years after the island was claimed as a British colony in 1841. When asked about them, Cho’s Hong Kong-born father refers to these bakeries as “Western-style” because “they feel very different in the context of normal Chinese food.”

But according to Cho, this also makes “the Chinese style baking so uniquely its own.” Sweet and savory ingredients like tropical fruit, green onions, sesame seeds, and lotus paste, a classic filling for mooncakes, mingle with custard and flaky pastry dough. Techniques vary too: Alongside fresh-from-the-oven baked goods, many Chinese bakery items are steamed or fried owing to the fact that Chinese households did not traditionally have ovens.

Mooncakes and Milk Bread embraces Chinese bakeries as a cultural cross-section, transporting readers not only to Hong Kong and mainland China but also America’s Chinatowns, from Cleveland to San Francisco, New York City, and beyond. It’s a cookbook that holds classic and contemporary recipes in equal regard. The proof is right there in the title.

“I think mooncakes and milk bread speaks to the whimsy and creativeness that’s in a lot of Chinese bakeries,” says Cho. “And I love the contrast between the two styles of baked goods,” with mooncakes being more “old-school” and milk bread having “a life of its own” right now.

Whether readers are seduced by the recipes that took generations to arrive in Cho’s hands or the recipes that are driven by her own creativity does not much matter to Cho. Her hope for the cookbook is simple: expose more people to the styles and perspectives behind Chinese baked goods to give more Chinese bakeries the chance to spring up in new places.

In the spirit of spreading awareness about China’s underappreciated baking traditions, here are seven essential Chinese bakery orders everyone should know.

Photo: Eat Cho Food

We hope you love this book we recommend! Just so you know, Matador may collect a small commission from the link on this page if you decide to purchase.

Mooncakes

Photo: VN STOCK/Shutterstock

Mooncakes are dense, round Chinese bakery items associated with East Asia’s Mid-Autumn Festival, which is observed on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month when the moon is said to be at its fullest. Styles vary by region, but red bean paste and lotus seed paste are traditional fillings. Salted egg yolks might also be added to the center to represent the full moon. Cantonese-style mooncakes like the ones Cho grew up eating are most common in the West. They have a chewy red-gold crust, opposite the flaky or crumbly crusts developed in certain parts of China, and typically have Chinese characters imprinted on the top.

Milk bread

Photo: chaechaebyv/Shutterstock

Popularized in 20th-century Japan, milk bread is an enriched bread and Chinese bakery staple that begins with a roux of flour and milk known as tangzhong. (Enriched doughs incorporate ingredients such as milk, eggs, and butter into their flour, water, and yeast mixtures to create a higher fat content.) The resulting dough can be formed into pillowy loaves, shaped into soft buns, or used as the base recipe for any number of Chinese baked goods.

Dan tat

Photo: MosayMay/Shutterstock

According to Cho, Chinese bakeries sell three types of egg tarts. Cantonese-style egg tarts, which were influenced by the British and have either a shortcrust or puff pastry base, and Macau-style egg tarts, or po dat, which can be traced back to Portuguese colonization and have a laminated base, caramelized filling, and hint of cinnamon. Growing up, Cho remembers egg tarts as a non-negotiable last bite anytime her family gathered to eat dim sum.

Jian dui

Photo: Aris Setya/Shutterstock

While they’re easy to find year-round in dim sum parlors and Chinese bakeries, jian dui are fried sesame balls that are traditionally eaten during the Lunar New Year. Similar to mooncakes, their round shape symbolizes family togetherness, while jian dui are also believed to bring wealth. Glutinous rice flour, red bean paste, a thick coating of sesame seeds, and good old-fashioned fryer oil give these sesame balls snack their characteristically crispy yet chewy texture.

Bo lo bao

Photo: kaykhoon/Shutterstock

“Every Chinese bakery must have a pineapple bun in their case,” writes Cho beside her recipe for bo lo bao, which is a version of milk bread that does not actually incorporate any fruit. The name for these buns derives from their appearance: After baking, their scored, “crackly cookie-like” tops are said to look like the peel of a pineapple.

Char siu bao

Photo: metita ungsumeth/Shutterstock

Another type of bun that’s essential to Chinese bakeries is char siu bao, or barbecued pork buns. The popular dim sum order consists of steamed buns stuffed with what Cho calls “essentially candied pork.” Both savory and sweet, char siu bao is a perfect example of the salt-sugar balance that backbones many Chinese baked goods and adds to the “magic of Chinese bakeries.” Steamed chicken buns are also sold in many bakeries.

Youtiao

Photo: Yu Xianda/Shutterstock

Youtiao, or Chinese donuts, look like a cross between a churro and a cruller. Often salted, the fried dough sticks are typically served at breakfast alongside jook, a savory rice porridge. Youtiao is also enjoyed plain with milk as a snack, as well as stuffed inside thick logs of sticky rice with pork floss, chili, assorted veggies, and egg in a dish called fan tuan.