Range anxiety was coined in 1997 by the San Diego Tribune, which reported on the GM EV1 and its drivers’ concerns over being stranded after running out of power. At the time, charging infrastructure was non-existent. Range anxiety had valid legs even a decade ago, when sub-Tesla EVs like the Chevy Spark and Nissan Leaf had a maximum range of around 80 miles and battery technology was nowhere where it is today. Then, being able to drive from one side of a large metro area to the other and back on one charge was a legitimate concern. Now, even more affordable EVs like the Chevy Bolt and the evolved Nissan Leaf S can carry you further than 200 miles on a charge, and high-end players like Tesla and Lucid are pushing 500 miles.

Don't Let the 'Range Anxiety' Myth Fool You. An EV Is Perfect for Your Next Road Trip.

Looking back at the catalog of internal combustion engine cars I’ve owned, none came anywhere near 500 miles per tank of gas. We’ve reached the point of technological advancement and ubiquitous charging infrastructure that range anxiety is officially dead as a valid concern — even to prevent drivers from taking an EV on a road trip. Still, the myth persists, so let’s thoroughly debunk the validity of range anxiety through data and a real-life test.

Combatting range anxiety: Factors to consider

Charging at Purgatory Mountain Resort near Durango while on a road trip to southern Colorado. Photo: Tim Wenger

The internet is rife with stories of travelers crossing the country in EVs, and forums highlighting where to charge and tips for optimizing their mileage. Alternatively, there have been reports of Tesla thwarting service appointments related to range decreases and projecting overly-optimistic expectations of its cars’ ranges.

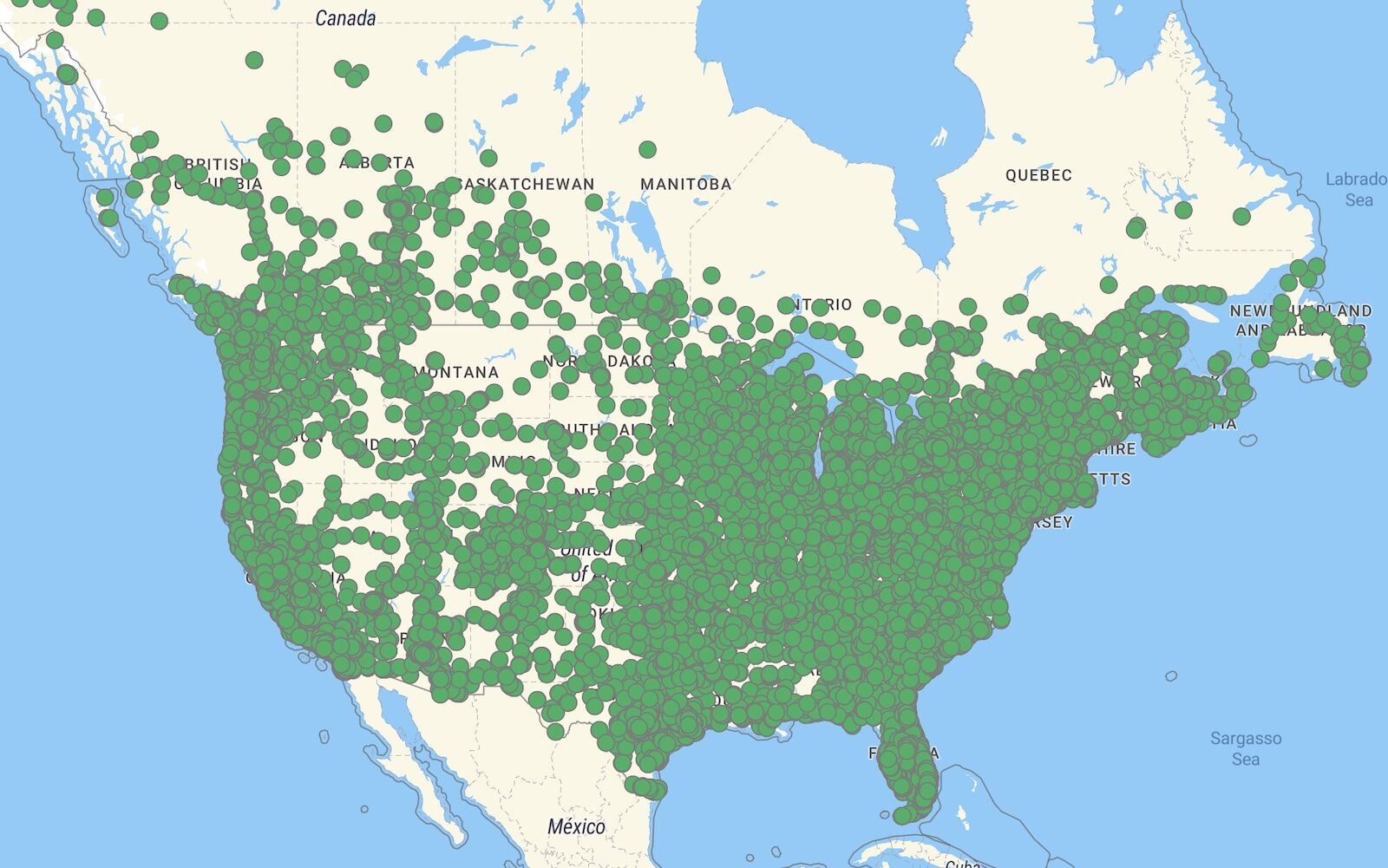

These are unfortunate but are the result of one company’s efforts and not reflective of where the industry as a whole is going. The future for EVs as viable roadtrippers is bright. The next generation of electric vehicles to be released by 2030 will contain newer battery technology that all but guarantees a range above 500 miles per charge. The ratio of EVs to charging ports is currently about 40 to 1 and will only get smaller. Compare this to gas pumps, of which there are 197 cars per pump.

In 2024, there are areas of particularly high charger density, such as the West Coast Green Highway, where drivers can find chargers every 25 to 50 miles. Rural areas often face a dearth – the greatest distance between chargers in the US is between Rawlins, Wyoming, and Casper, Wyoming, a distance of 118 miles. On average, drivers face between 50 and 100 miles between chargers in many rural areas. Still, this is hardly an issue of practicality, as nearly all EVs released since 2020 can cover a distance greater than 118 miles.

More than 1,000 EV charging stations came online in the second half of 2023, and 2024 looks to have similar growth in charging infrastructure. By the end of this year, the federal government expects over 7,500 charging stations to be available across the country. Year over year going forward, more charging stations will arise and an increasingly higher percentage will be DC Fast chargers.

Beyond charging infrastructure are other means of combatting concerns over an EVs range. Most notable is regenerative braking, a process that uses the car’s kinetic energy when braking to recharge the battery while you drive. This can significantly improve range when driving casually, and if descending in altitude its even possible in some cases to arrive at your destination with more power than when you left. Case in point, when I drive home from the ski area nearest to my house, a distance of about 27 miles and an elevation gain of about 3,400 feet, I arrive with about 15 miles more charge than when I left the resort. This offsets much of what was used to climb to the ski hill.

Many forthcoming charging stations will be installed at end-of-day locations such hotels and Airbnbs, of which more than 1 million now have EV chargers. As shopping centers and other commercial areas adopt fast charging, it will be increasingly possible to park somewhere, run your errands or do your activity, and return to a fully charged vehicle.

Putting an ‘affordable’ EV to test on a road trip

EV chargers are now common even in rural areas like Montrose, Colorado. Photo: Tim Wenger

In November 2022, I put down a $2,000 deposit for a 2023 Chevy Bolt EUV, listed at just under $30,000. We chose to wait until January 1 to purchase because doing so qualified the vehicle for the $7,500 federal tax rebate under the Inflation Reduction Act and a $2,000 tax rebate from the State of Colorado (so much for EVs being “unaffordable” compared to ICE vehicles). We picked up the car from the dealer on January 2, 2023.

The car’s claimed range of 210 miles proved roughly accurate over a few months of using it as a daily commuter around our home in Colorado’s Grand Valley. Once the snow had melted off the mountain passes, we felt comfortable testing the car on the 230-mile trip to Denver on I-70. My concerns leading up to the trip were:

- How would the continuous incline and decline in elevation throughout the drive impact the mileage, particularly the nearly 2,000-foot gain going over Vail Pass

- Conversely, how much power would we regain through regenerative braking while descending Vail Pass and other declines in elevation

- ChargePoint listed more than 100 charging stations between our house and Denver and within a couple miles of the interstate. Would they be occupied? Broken?

- Most of those chargers were Level 2 – meaning it would take a few hours to fully charge the car. How would this impact what is traditionally a 3.5-hour drive?

- Our 1.5-year-old daughter was coming with us – would a charging delay make the trip unbearably miserable for her, and vicariously, for us?

With a full charge, we hit the road around 10 am. The dashboard showed we had 237 miles of power, which we’d learned through trial and error amounted to about 210 miles of city driving. Conversely, to internal combustion engines, EVs often perform better in urban environments than on open stretches of road because of the power regained through regular braking. I’d learned some tricks to go easy on the pedal when descending so that we’d effectively gain maximum power each time we went down a hill, and I employed these tactics throughout the morning.

We planned to stop halfway, in the town of Eagle, and plug into a ChargePoint charger, located in a shopping center parking lot, while having lunch. 123 miles and a little under two hours later, we pulled into Eagle with 62 miles left on the charge. We’d used over ⅔ of the battery charge for just over half of the drive. The Bolt EUV gains about 25 miles per hour on a Level 2 charger, and we planned to spend two hours eating and visiting a bookstore that we love. We returned after 100 minutes to 111 miles of power. After spending a few minutes getting our daughter buckled in and slowly settling ourselves, we hit the road with 120 miles of power. On paper that would be enough, but Vail Pass lied just ahead.

With all these stations to choose from, the only anxiety I’m feeling is over which ones to stop at. Photo courtesy Energy.gov

Going up the pass, I stayed in the right lane and avoided flooring the car. It climbed just fine as the notoriously aggressive I-70 traffic flew by us in the left lane. At the top, we’d driven 30 miles since Edwards and had 58 miles of range left. I’d need to really optimize the regenerative braking going down the pass for us to have enough mileage to reach Denver.

Going down, I held the gas pedal below the break-even power line the entire way so that we’d gain as much power as possible. We reached the bottom of the pass, just outside Frisco and another 11 miles on, with 71 miles of range and 72 miles to go.

Cruising through Summit County, I gained another five miles which we promptly lost on the climb up to the Eisenhower Tunnel that separates Summit and Clear Creek Counties. But most of what remained of the drive was downhill – 57 miles with 70 miles on the charge. I treaded lightly on the accelerator and we reached Denver at 4 pm with 31 miles to spare. Through a nap and the use of many toys, our daughter kept herself busy throughout the drive.

This drive happened on an interstate highway with ample chargers available if we’d needed them. We did see drivers at a few of them, but most were open. We’ve also put the Bolt EUV to the test on two-lane highway road trips of similar distances, and not once has there been a problem finding a charger when needed. After almost 18 months with the EV, we’ve never had a single issue with range, either locally or when headed out of town.

These experiences, and the strategizing they required to execute, happened in 2023 and early 2024. Range anxiety will only become increasingly obsolete in the coming years due to the increased battery technology and growing commonplace of charging infrastructure. Apps like Chargely, which offers user-sourced information about EV chargers around the country, and company-specific apps like ChargePoint, make it easy not only to find chargers, but to know whether they are functional and available. Good riddance, range anxiety, you won’t be missed.