Strategically placed by a bend in the Niger River along the main trade route through the Sahara desert, Timbuktu was a hub for merchants and travelers between the 11th and 16th centuries. This constant flow of people brought with them ideas and experiences, and Timbuktu slowly became a center for Islamic culture and intellectualism. The hundreds of resultant mosques and libraries have been drawing tourists, scholars, pilgrims, and admirers to Timbuktu for nearly a thousand years, yet in 2012, the remaining artifacts of this legacy were nearly destroyed in a handful of months.

Timbuktu’s Legacy as the Center of Muslim Culture Is in Danger of Being Lost Forever

The perpetrators were Ansar Dine, an extremist group with ties to al-Qaeda. Among them, the man who served as their chief of police and de facto head enforcer, Al Hassan Ag Abdoul Aziz Ag Mohamed Ag Mahmoud, is currently being tried in Den Haag, Netherlands, by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for both crimes against humanity and war crimes.

Al Hassan’s lawyers are arguing that he is unfit to stand trial. At preliminary proceedings, when presented with each separate charge against him, he has refused even to enter a plea, simply stating, “I cannot answer this question.”

One of the primary beliefs of Ansar Dine surrounds the sanctity of the teachings of Islam, and that secular literature is considered idolatrous. In an effort to remove such “threats” as part of their occupation of Timbuktu and the rest of Northern Mali, Al Hassan headed the intention to completely destroy a thousand years of teachings, mostly handwritten in Arabic, that had been carefully stored in the hundreds of libraries throughout Timbuktu.

Although Al Hassan’s efforts were largely thwarted by a handful of librarians and laypeople, many manuscripts were publicly burned or otherwise destroyed. The cultural artifacts that were saved were either taken away from the city or hidden.

But now the relics they managed to stow in Mali’s capital, Bamako, face a greater threat to their destruction: natural decomposition.

The race to preserve the intellectual history of Northern Mali from the climate of its capital is being treated just as seriously as the unlawful actions of Ansar Dine. Today in Bamako an international restoration and digitization project is still underway, but it is only 20 percent complete. The ultimate goals are threefold: to restore the manuscripts and devise methods to prevent further harm, remove the threat of insurgency in Northern Mali, and return these artifacts to their rightful home in Timbuktu.

The insurgency

In 2012, taking advantage of an already-occurring anti-government rebellion of the local Tuareg people, Ansar Dine managed to wrestle a terrifying, strict control over Northern Mali. Their goals included installing a hyper-conservative sect of Islam, this being in direct conflict with the region’s reverence for the secular pursuits of literature and science.

Their methods of control were extreme. They recruited soldiers from the population, offering small stipends, thus tempering resistance. They patrolled the streets, swiftly enforcing new laws they had implemented without trial or process. They were particularly strict with women who frequently suffered severe physical punishments for the smallest misdemeanors.

To many citizens of Timbuktu, its libraries and books are indivisible from the city itself — Timbuktu would simply cease to exist as it has for the last millennia without them. But to Ansar Dine, these manuscripts were considered haram — forbidden — and among their other campaigns of control, they sought to destroy them all.

So important is the literature of Timbuktu that destroying it, the ICC believes, should be considered a war crime. Their first precedent-setting case that argued this was in 2016, when Al Hassan’s cohort, Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi was tried in Den Haag. He was charged with attacking religious buildings and historical monuments in Northern Mali. Nine mausoleums and a mosque were cited in court as being targets of his destruction for which he was ultimately convicted. Al Mahdi was sentenced to nine years in prison, and the ICC likely seeks to use this legal precedent to similarly convict Al Hassan.

While the Insurgency was largely quelled in 2013 with the help of French troops, the threat has not dissipated completely. Even though Al Hassan is currently imprisoned in Den Haag, Timbuktu has not yet fully recovered, and the relics still require additional measures of protection for safekeeping.

Today, commercial flights to Timbuktu have ceased altogether, and tourism, long a booming industry for the ancient city, is almost non-existent. Once an influential oasis, Timbuktu now sits effectively more isolated than ever.

The preservation

Photo: Teo Tarras/Shutterstock

When Ansar Dine began to burn books and destroy libraries, many feared that a thousand-year legacy would be lost forever. But Abdel Kader Haidara, himself owner of a library, refused to let the history of Timbuktu go up in smoke.

Through a translator, Haidara shared with PBS how they managed to save some of the artifacts: “We smuggled the manuscripts out very slowly, little by little, over a period of six months. We took them out of Timbuktu in 4×4 SUVs. We brought them to Bamako. We also stockpiled them in small boats about five miles outside of Timbuktu and took them 375 miles away.”

Haidara, other booksellers, and members of the resistance in Timbuktu were presented with the massive challenge of saving the written history of a nation on the fly. Via a clandestine system that involved methodically transporting a few books at a time, Haidara and other librarians, historians, and laypeople were able to save about 200,000 manuscripts in total.

“We formed several committees: one in Bamako, one in Timbuktu and another at an intermediate point on the route,” Haidara explained. “Some took care to make sure that the material was accommodated and remained intact inside the car. Others accompanied me to Bamako, and there the manuscripts were removed from the third reception committee and placed in houses where they would be safe.”

“We couldn’t take the manuscripts with us,” said Haoua Toure, owner of a private library in Timbuktu. “The occupation took us by surprise, but people had to decide what to do. So people started to find ways of hiding their manuscripts before leaving.”

Many were forced to bury their precious books in the Saharan sands, taking with them only a list of the precise coordinates where they lie and the hope that they could one day be unearthed intact.

Thanks to their efforts, the majority of Timbuktu’s literary artifacts were saved, though sadly, much of what could not be secreted away or buried for safekeeping was burned by insurgents and lost forever.

The restoration

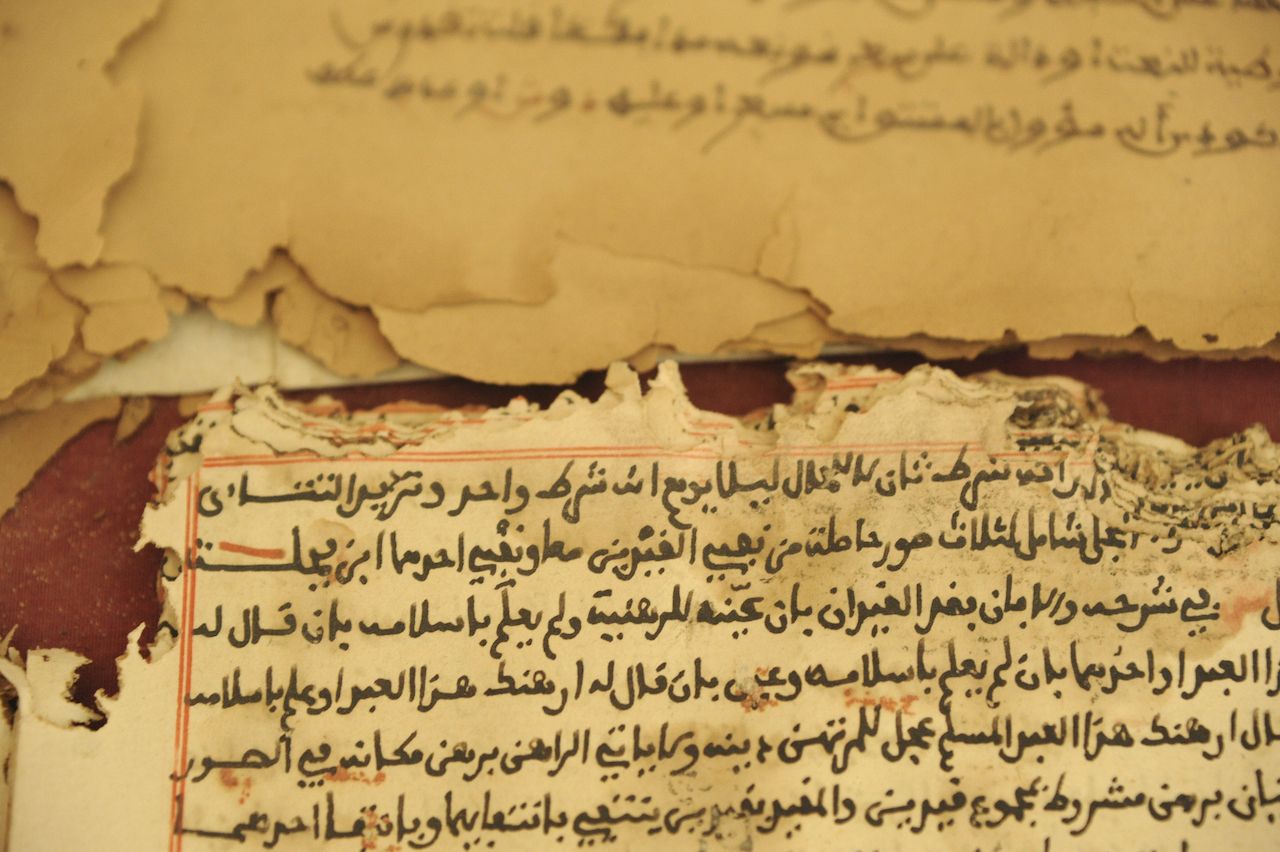

Both public and private libraries in Timbuktu have accumulated hundreds of thousands of manuscripts — some dating as far back as the 12th century — that collectively form what some believe is the single most important collection of literature in the world.

The fragile papers that were naturally preserved for hundreds of years by Timbuktu’s arid Saharan climate are now vulnerable in Bamako’s humidity. This means that what began as an effort of mere transportation quickly became a full-scale restoration and digitization project that is still ongoing.

Each book must be carefully cataloged. The manuscripts that are in good shape must be read and summarized, photographed, then placed in boxes that are specially designed to ward off further deterioration.

One of the restorers on the project, Eva Brozowsky told DW, “if one person did this, we would have more than a century of work. The more people who can collaborate, the greater the financial need but the faster the result.”

The books themselves cover such a wide range of topics: astronomy, medicine, music, and much more. The wealth of knowledge at stake is enormous. They are a link between the nation’s past and present and are inextricably tied to their history of Timbuktu.

Meanwhile, the manuscripts that failed to make it out of the city remain largely buried. Again, Haoua Toure said of her own buried cache, “We know the exact coordinates of every one of our manuscripts, but we can’t unearth many of them because it’s still dangerous here, so we can’t start organizing them yet. They will remain in hiding. It’s really a problem, and it’s much better that it remains a secret, for the security of all of us.”

In parallel to the manuscript restoration project in Bamako, Timbuktu is getting a facelift. The damage to their mosques and libraries is being repaired, the city being readied for when the threat of violence subsides, and their treasured manuscripts can be returned to their rightful home in the Sahara.

But COVID-19 has brought a new threat. A rise in extremism has been noted around the world, and groups operating in the east of Africa like Boko Haram, al-Qaeda, and even Ansar Dine have become more active in 2020. Meanwhile, in Bamako, social-distancing protocols have thrown a wrench into restoration efforts, slowing their progress.

Al Hassan’s trial is currently on hiatus but is scheduled to resume on August 25, 2020.