I’m standing across the street from Fenua Ma Tema’e, the prettiest public dump on the dreamy Tahitian island of Moorea. The dump, on the inland side of the island’s ring road, is surrounded by coconut palms and tucked into the deep green folds of a steep mountain. I’m on the other side of the street, in the parking lot of Golden Lake, a nondescript restaurant and “snack,” or fast-food vendor, staring at a display case to decide whether I really want to try a local specialty: the chow mein sandwich.

Chow Mein Sandwiches, Mustard Wontons, and Fruit: a Tour of French Polynesian Street Food

I inspect the pre-packaged sandwiches. They look okay, but I’m still not convinced. Chow mein, most people know, is a noodle dish. Noodles, most people know, don’t fit well into sandwiches. Unorthodox sandwiches, most people know, are usually not recommended. But what do I know?

“Whoever came up with this must have been drunk or stoned, because who thinks of putting noodles in a sandwich?” says Heimata Hall, founder of Tahiti Food Tours, who is taking me and a couple of friends on a tour to sample Tahitian street food. My traveling companions and I contemplate skipping the noodles-on-a-roll altogether. “Look,” says Hall, trying to persuade us, ”I had to try all the chow mein sandwiches on Moorea and this one is the best. A lot of places are mostly noodles, but this one is a nice blend of chicken and noodles on a fresh baguette. And the sauce [a plum sauce similar to the duck sauce in packets offered at US Chinese restaurants] brings it all together.”

Photo: Mark Orwoll

Hall is never going to win the salesperson of the year award. Nevertheless, I take a deep breath and say, “What the hell…” The sandwich turns out to be a treat. The taste is rich, a little gooey, and there’s a good amount of chicken (and noodles) in the mixture. But there’s no getting around the mess they make, as the noodles and sauce tend to squirt out at one end or the other. People generally stand at a 45-degree angle when they eat a chow mein sandwich.

Hall watches our reactions and smiles. “I told you! Pretty good, right?”

Yes, pretty good indeed — an eye-opener. And opening our eyes was the point of eating here and the other holes-in-the-wall we were about to visit.

Wontons and walkie-talkies

Photo: Mark Orwoll

Hall had picked us up at our hotel, Moorea Beach Lodge, in his comfortable minivan at 8:30 AM, ready to introduce us to local culture, a fair amount of weirdness, and more food than anyone should be expected to gobble down between wake-up and 1:00 PM, whether in Moorea or anywhere else. The personable Hall grew up in Moorea and knows its cafes and roadside stands better than most, thanks to his almost academic devotion to the subject. He’s also trained in the culinary arts, having studied at the Pacific Culinary Institute in Honolulu, Hawaii.

On the agenda were several cafes and snacks — informal eateries, often with outdoor seating, that specialize in local home-style meals: cheap, filling, and, often, international.

“You don’t need my help to find fancy restaurants,” Hall says as we drive onto the island’s ring road for our first destination. “But I’m going to show you the street food that we locals eat.”

Photo: Mark Orwoll

Our first stop: Snack Rotui. The locals know it as Atignon, but no one seems to remember why. The tables and benches are outside, sort of like an A&W Root Beer stand you might have found off the highway between San Bernardino and Barstow in 1962. Except, here, there are lapis waters offshore, curving palm trunks line the beach, and volcanic peaks surround us on three sides. We order wontons filled with minced chicken and topped with carrots and scallions, but the spicy mustard is what makes them unique and memorable.

When Atignon runs out of any dish, the counter people get on their walkie-talkies and radio home, just down the road, where the food is prepared. Then someone brings over whatever is needed. After we finish our wontons, I notice a teenager in a van delivering several metal boxes of freshly prepared food. Not exactly cutting-edge, but it’s effective.

Fruit at the ferry dock

Photo: Mark Orwoll

Next on the agenda: Supermarche Pao Pao, a small, nondescript country grocery store. “We’re going to see if they still have some rēti’a,” Hall says, adding, “they usually run out of it pretty early.”

We walk swiftly inside — apparently, speed is required to beat the crowds — and find our target on a tray by the breakfast cereals and soft drinks. The rēti’a looks like raw fish packaged in Saran Wrap by your well-meaning but hungover aunt. It’s a paste made of coconut water (the natural liquid inside the nut), coconut milk (squeezed from the shredded white pulp), sugar, and tapioca starch, which is then baked until it gels enough to cut in strips. But Hall wants to hold these for later, along with a couple of pineapple turnovers, and hustles us back into the van.

As we drive to the next place on the list (we’re basically sampling one or two dishes at each stop), I notice what appears to be homemade stalls on the roadside, each with a crude table and sometimes a shade covering. Hall sees me looking at them.

“You see the tables on the street?” he asks. “People who live on these roads just pull the fruits off their trees and sell them. You can find pumpkins, mangoes, bananas, avocados, all fresh and good.” Other local produce includes eggplants, zucchinis, bok choy, radishes, carrots, cucumbers, and sweet potatoes.

Hall drives the van into the parking area of the main ferry terminal, where most visitors arrive for day trips or longer stays from Papeete, which is across the channel on Tahiti. It’s an unlikely place to find local foods, but Hall wants to show us the fruit stand here. He says there are always five or six varieties of bananas, along with passionfruit, soursop, huge avocados, and our next taste sensation, mangue bonbon chinois, or more simply, “crunchy mangoes.” This special sort of local mango is called “bent butt,” named for its peculiar, less-than-attractive shape. It is indeed crunchy, like biting into a Red Delicious apple. What makes it even more special is the plum powder that the woman who sells the fruit sprinkles on the slices.

Photo: Mark Orwoll

“This is definitely one of the local snacks that most tourists never know about,” Hall says. The plum powder, also called li hing mui in Chinese, is tangy, salty, sweet, pinkish-orange in color, and adds a zest to the experience. But it’s the sharp crunch of the mango that I most remember.

At the fruit stand, we also try mape (pronounced mah-pay), a large nut cooked for three to four hours in a hot pot. Think of mape as a Polynesian chestnut. To prepare it, the shell is cracked and the nut boiled in water. The preparation calls for a little sugar in the cooking water, but not too much.

“We love to just buy a bag of mape and snack on them,” Hall says. I found them to be bland, but far healthier than biting into a Mars chocolate bar, which has a similar consistency.

Everybody knows Moz

Photo: Mark Orwoll

“Next stop: fish!” Hall cries, gunning the van down the ring road as we pull away from the aforementioned Golden Lake. We pull into a parking lot next to a real estate office in Moorea’s “downtown,” which is a short strip of retail buildings. “This is Moz Café,” he says, pronouncing the name like one of the Three Stooges and pointing to the second floor of a small commercial building. “It’s one of my favorite places on the island.”

Seated in the unpretentious cafe, we have raw marinated tuna, or poisson cru (“our national dish,” says Hall), with coconut milk, onions, cucumber, and carrots. The poisson cru is like tasting Tahiti on a fork: rich with the flavor of oceans and fresh vegetables, a marriage of land and sea. On the side, we’re served a Chinese-immigrant-inspired (despite its name) mille-feuille du tartare, a crispy, flat wonton topped with avocado, marinated tuna, and alfalfa sprouts and eaten like a tostada. Two kinds of banana po’e round out the deliciousness. Po’e stems from a money-saving way to avoid wasting food. If you have over-ripened fruit, you don’t throw it away; you mush it into a puree, put it in a banana leaf, and bake it in an underground oven. You want street-food dessert? Ask for po’e.

Beans, macaroni, and rice

Photo: Mark Orwoll

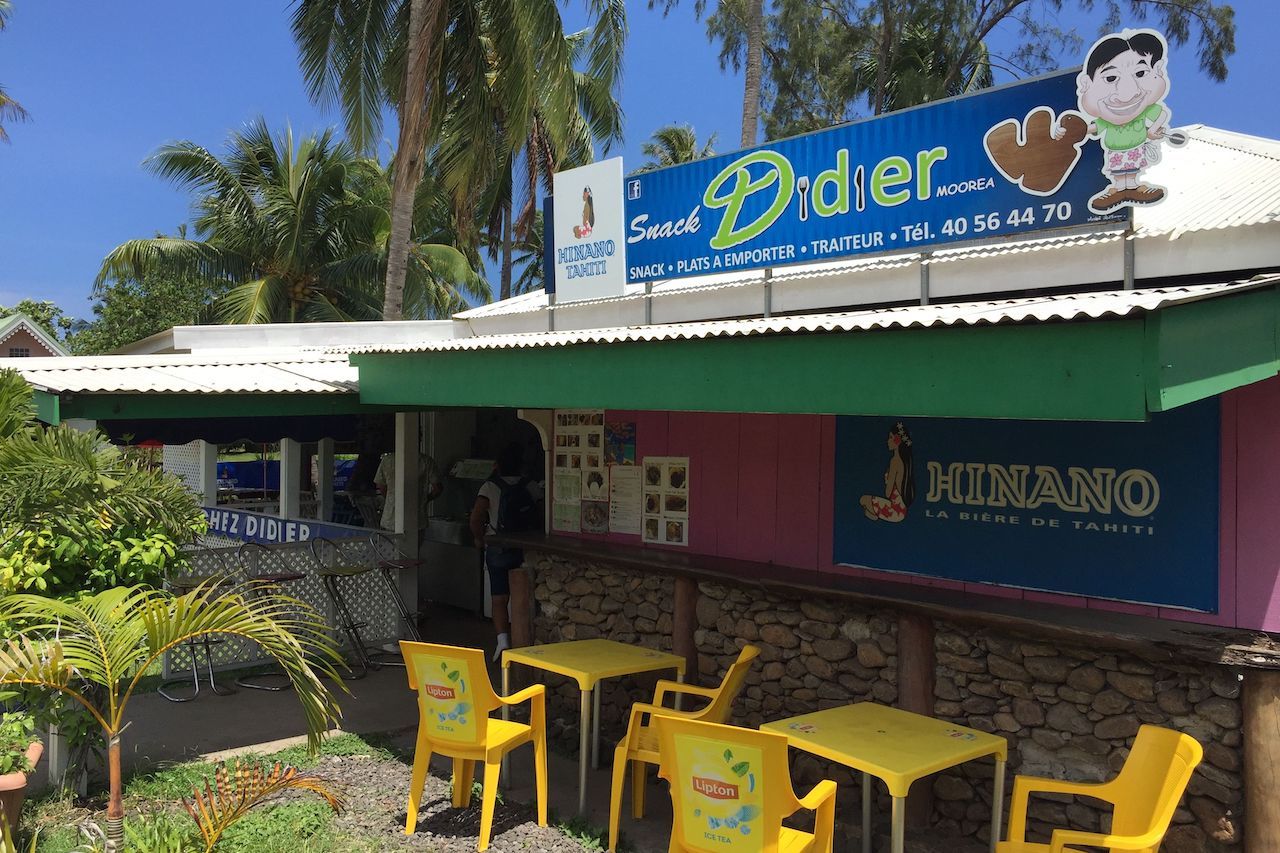

By this point, we are seriously full — slogging, can’t-bend-over-to-tie-my-shoelaces, loosen-the-belt stuffed. And so, of course, we walk next door to Snack Didier for a plate of ma’a tinito: red beans, macaroni, bite-size chunks of pork, bok choy, and carrots, all poured over rice. Yes, that’s right — beans and macaroni and rice in the same dish. I gained five pounds just reading the menu. The concoction, inexpensive and hearty, was brought here by Chinese immigrants 150 years ago. Now it’s a staple throughout French Polynesia. “If there’s one dish besides poisson cru that resonates through all the islands,” Hall says, “this is it.”

Diners at Snack Didier sit on a covered patio at picnic tables and on wooden or plastic chairs. To call it down-home would be like calling a TGI Friday’s upscale. “This is definitely a local favorite,” Hall says, looking around the tables with a huge smile. “A typical local lunch spot.” There is something Caribbean-like about the place and the food, especially with the red beans and pork, but the rice and store-bought macaroni give it a whole new sensation.

A fried fish truck turned into a seaside cafe

Photo: Mark Orwoll

Our penultimate stop is Snack Mahana, which began as a food truck parked in front of the owner’s house and now is a popular 60-seat outdoor cafe on a lagoon. The owner built a deck over the water, and we take a seat there. Schools of fish swim past our feet. Deep-fried mahi-mahi with fresh coconut milk made the truck’s reputation. We order it. Ribbons of fresh tuna carpaccio are called for. Done. Thick french fries, mountains of white rice, and Hinano beers soon follow.

It’s just past noon and the place is packed, including some adventurous tourists. “I tell people they better come here by noon or they won’t be able to get a table,” Hall says.

Dessert under the palms

Photo: Mark Orwoll

We waddle back to the van and our final stop: a pretty public beach lightly shaded by palms. Three twenty-something men with a radio are bopping to Tahitian reggae and drinking beer. Some school kids giggle their way past us. The sunshine and aqua water and palms make me delirious — or is it everything I’ve consumed in the past few hours? A Tahitian food coma?

Hall, who recently opened a similar tour operation in Papeete and hopes to start a restaurant in the near future, opens a cooler and brings out the rēti’a and pineapple turnovers we purchased earlier that morning. The grayish-brown, fishlike consistency of the rēti’a is less than appealing. But in for a penny, in for a pound. So when Hall asks who wants some, I feebly raise my hand, weak from surfeit. “…I…do…”

The rēti’a’s texture is gelatinous, almost gummy. It tastes only slightly sweet, and just a little coconutty. I’m not sure I’d end every feast with rēti’a, but right here, right now, on a gorgeous beach in Tahiti, it turns out to be exactly what I want.

Tahiti Food Tours offers street-food tours by appointment. The price is $125 per person for a roughly four-hour excursion, including all meals, snacks, and transportation.