Until just a few decades ago, simply stepping outside of the male-dominated household was an act of rebellion. Yet women still chased freedom in faraway places, writing about their experiences in order to challenge restrictive cultural norms. These weren’t just wealthy European spinsters but mothers, scientists, and alpinists from diverse global cultures. Biruté Galdikas studied orangutans in the jungles of Borneo, bringing conservation and eco-advocacy to the public with her memoir Reflections of Eden. In Isabelle Eberhardt’s diary, The Nomad, she describes dressing like a man to find acceptance with indigenous North African tribes. And Zora Neale Hurston initiated herself into the voodoo practices of Caribbean islands though her anthropological travelogue, Tell My Horse, didn’t gain attention until after her death.

In pushing the limitations of their own locations, ladies also campaigned against the status quo. So no matter how challenging your own travel restrictions might feel right now, these books will remind you that women have a history of traveling beyond stereotypical boundaries — both through their movements and their words.

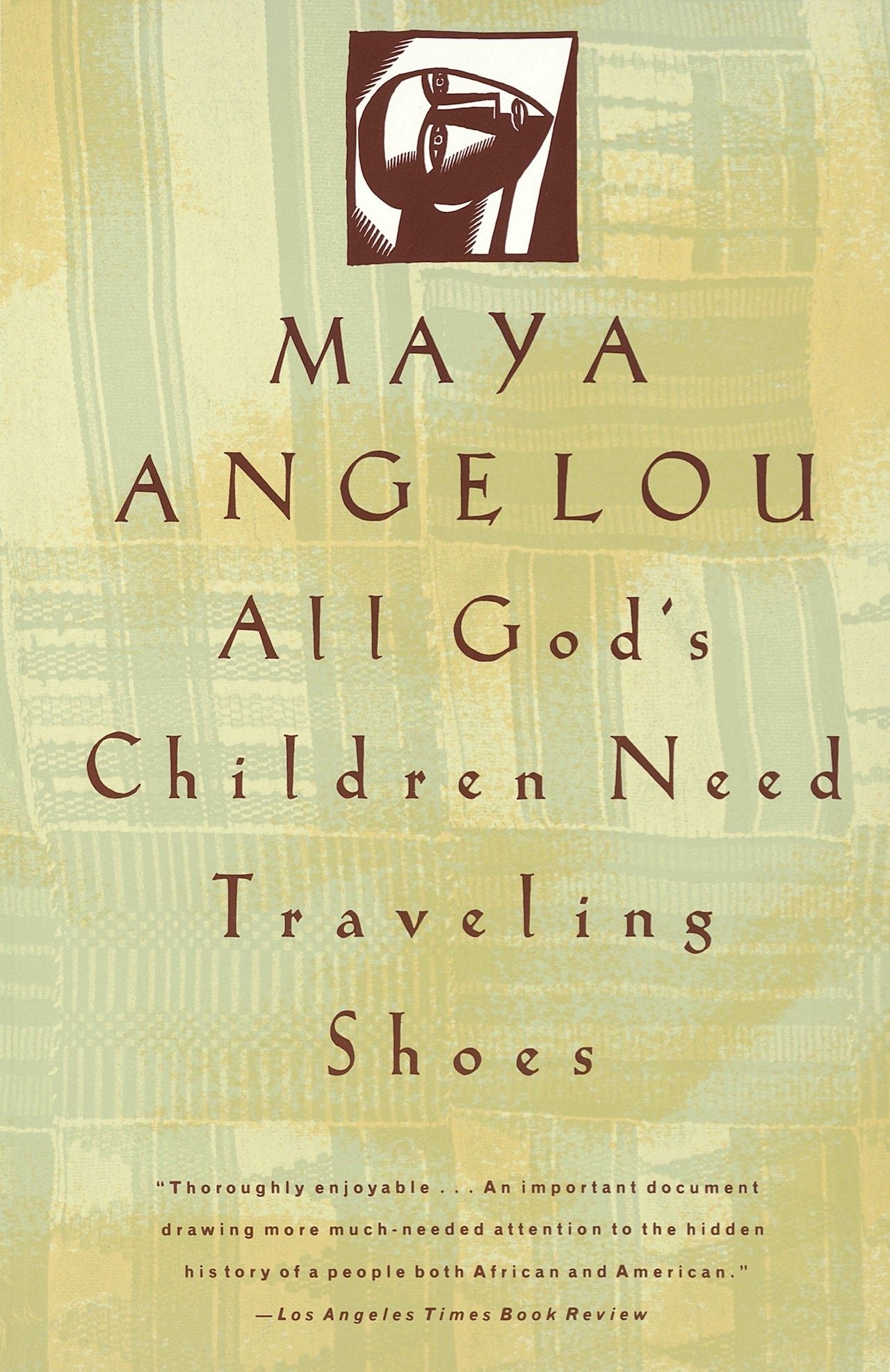

1. All God’s Children Need Traveling Shoes by Maya Angelou

Photo: Penguin Random House

Angelou only intended to help settle her son into university in Accra, Ghana. But after he survives a harrowing car accident (not a spoiler!) during his first days in the capital city, the worried mother decides to stay put for his full recovery. What follows is Angelou’s own version of settling in, exploring West African culture, and connecting her family’s history of enforced slavery in the American South to their roots in the Mother Continent.

While many readers meet Angelou through her first autobiographical work, I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings, this is the fifth title in her self-reflective series. The American poet and Civil Rights activist was one of the first Black female writers to discuss her personal life through literature, portraying both the positive and negative spectrum of human experiences.

Much of her time in Traveling Shoes is spent seeking belonging in a place where skin color doesn’t draw attention, yet Angelou’s Americanness still sets her apart in ways she struggles to accept. Written in 1963, the book proves Angelou’s idea that “home is the place where one is created” — an absorbing sentiment regardless of your heritage.

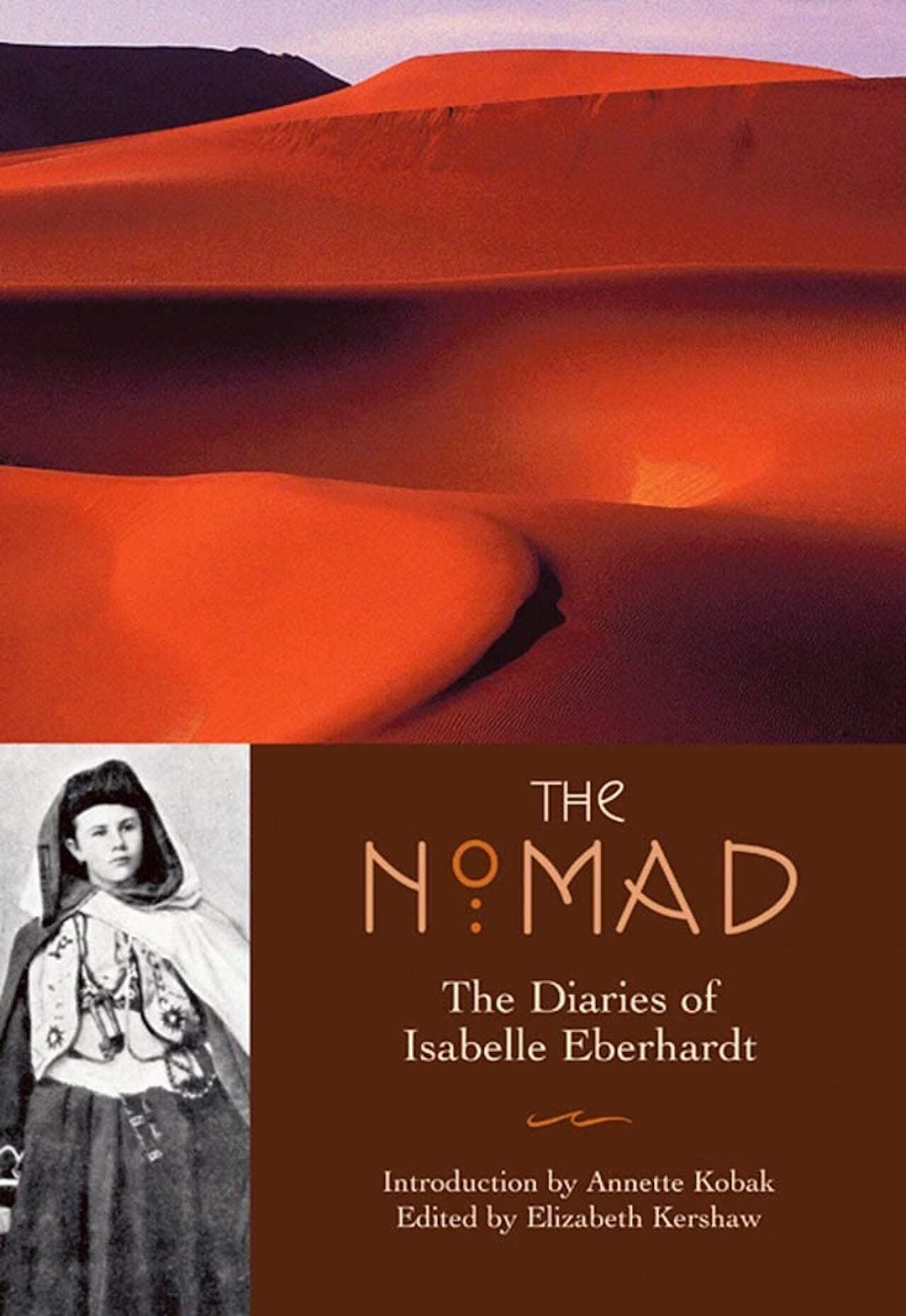

2. The Nomad: The Diaries of Isabelle Eberhardt by Isabelle Eberhardt

Photo: Interlink Books

Eberhardt could be called an escapist, in every sense of the word. Born illegitimately into a Swiss-Russian family, the 20-year-old fled Europe’s middle-class society in 1897 in search of nomadic culture in Northern Africa. Disgusted by the attitudes of French colonial settlers in Morocco and Algeria, she sought out indigenous tribes, and when femininity threatened to limit her explorations, the young adult dressed in male clothing and traveled under the name Si Mahmoud.

Her diaries are an intense emotional journey, full of acute observations on the landscape and a developing sense of self. You may or may not be shocked by her experiments in drugs, sex, Sufi spiritualism, and whatever else disconnected her from the physical world.

While Eberhardt never openly voiced a specific gender identity, she’s championed as an early pioneer in gender fluidity and one of the first LGBTQ+ travelers. Also not addressed in this book: her shocking death at age 28 in a flash flood that some believe was not an accident.

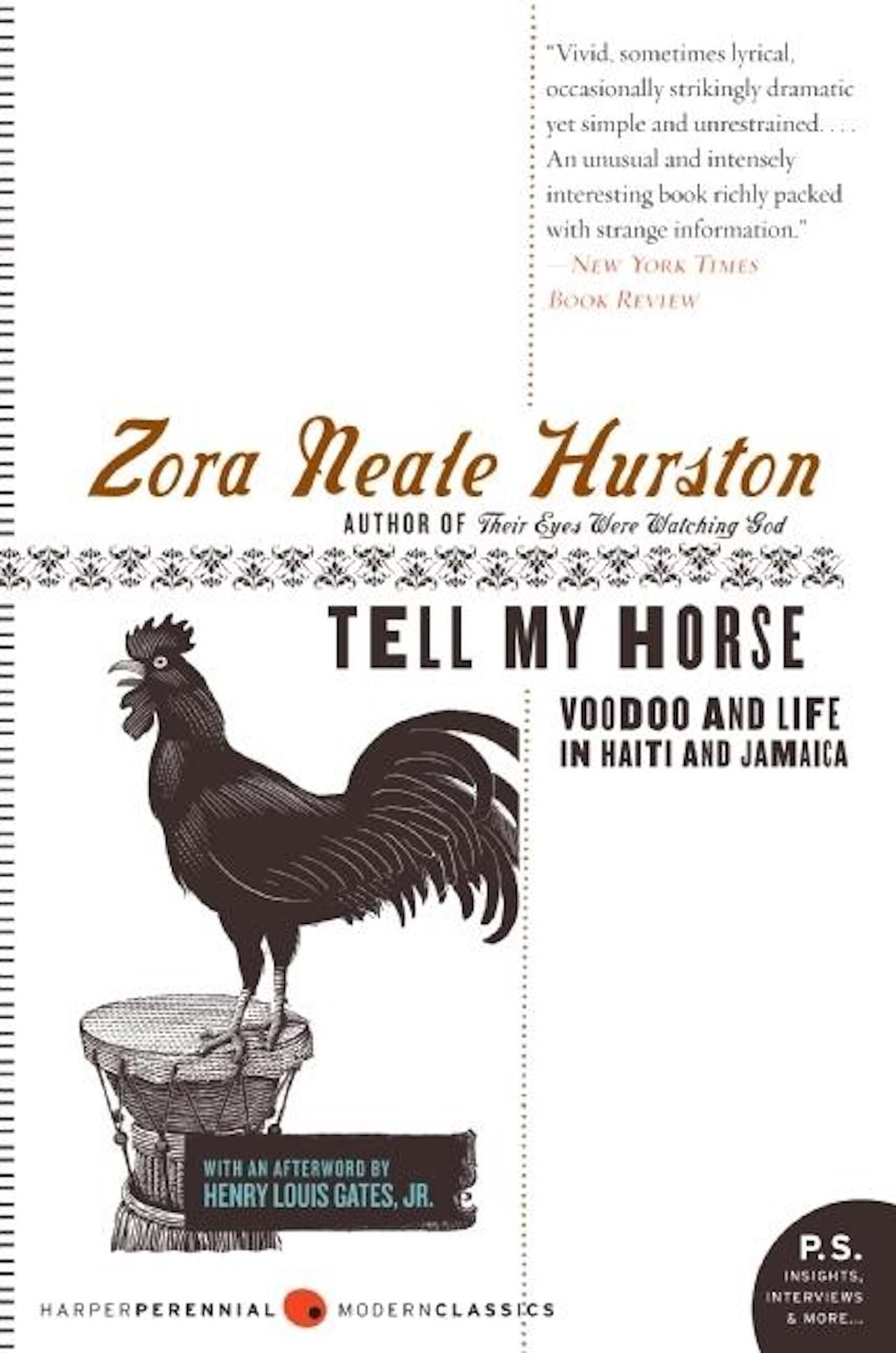

3. Tell My Horse by Zora Neale Hurston

Photo: Harper Collins

In an era when women were expected to be teachers or nurses, Hurston traveled to Haiti and Jamaica on a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship to study Afro-Caribbean religion. Using folklore as a lens to better understand culture, the American writer and anthropologist initiated herself into the voodoo practices of these islands.

Tell My Horse has been described as dark and strange, and it received mixed responses when it was published in 1938. Hurston doesn’t waste too many words explaining local vocabulary or backstories, which forces you to jump straight into her sensory environment. This makes for an unsettling and slightly confusing read; the book feels like a vintage folktale — all the more spooky because it’s real.

Keep in mind that Hurston — who also wrote the modern classic Their Eyes Were Watching God — never found financial success for her writings on Black culture. At her death in 1960, she did not have enough money saved for a headstone, and her grave went unmarked for 13 years.

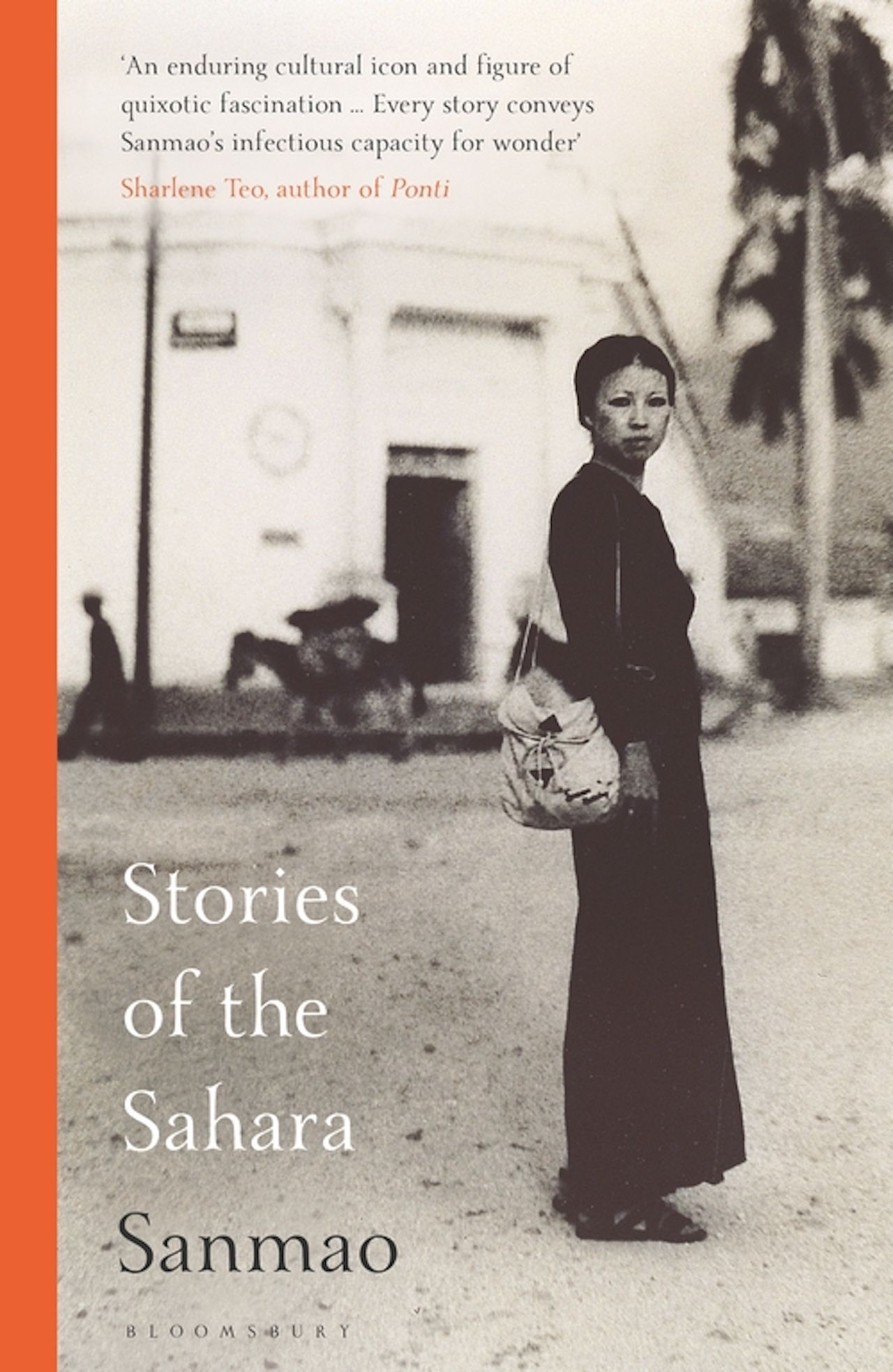

4. Stories of the Sahara by Sanmao (translation by Mike Fu)

Photo: Bloomsbury

As a kid, Echo Chen Ping revealed in National Geographic’s multicultural images and stories. Though conservative Chinese culture did not endorse independent female travel — and the post-Mao region felt isolated from foreign influence — Echo used education as her ticket out.

After studying in Europe, she decided to become the first female explorer to cross the Spanish territory of El Aaiún, which is now part of Western Sahara. Echo took up the pen name Sanmao and wrote with a youthful curiosity of the indigenous Sahrawi, desert domesticity with her Spanish husband, and the traveler’s eternally frustrating wish to be somewhere else.

Stories was released in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan in 1974, instantly inspiring a generation of Asian women to reconsider their world views. Yet the travel memoir did not receive an English translation until 2020 — just in time to motivate a new generation of women, trapped at home by a global pandemic.

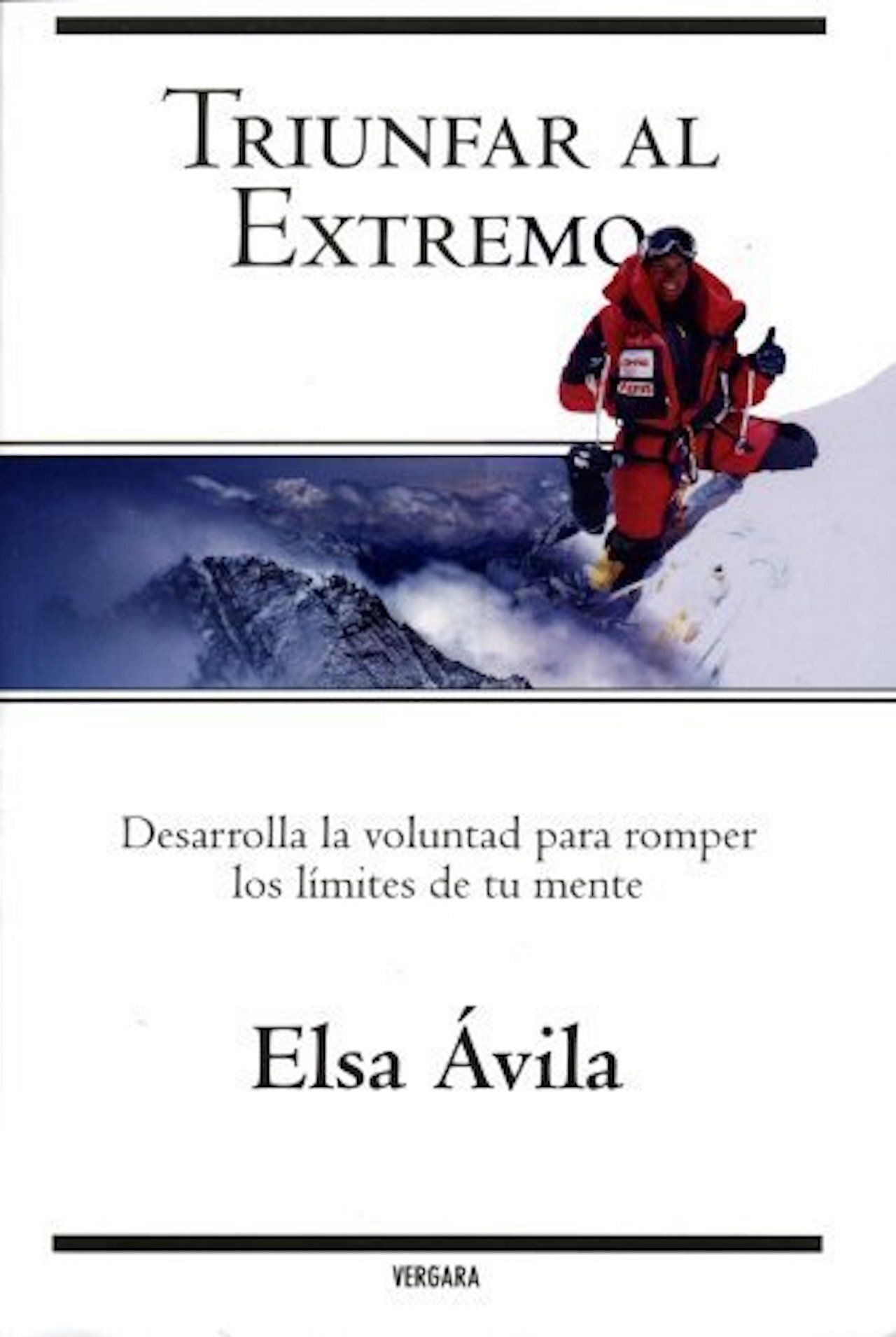

5. Triunfar al Extremo by Elsa Ávila

Photo: Elsa Avila

English speakers are still waiting on a translation of this travel memoir from Mexican climber Elsa Ávila. Or, as she’s also known, the “first Latin American female to summit Everest.”

What’s more incredible than this world ranking is the story behind the historic 1999 summit effort. Ávila began rock climbing at age 15, scaling multiple famous rock faces and then climbing into the elite “eight-thousander” list of mountains over 8,000 meters. While climbing Everest’s southeast route in 1989, she showed signs of potential respiratory failure, and the expedition turned around, just 302 feet from the top.

Her refusal to give up on this goal finds a powerful voice in Triunfar. Ávila returned 10 years later, this time finishing the climb and gaining international renown for her courage and commitment. You’ll need to read the book to learn more; Ávila gained international status, but only the male members of her earlier expedition have Wikipedia pages.

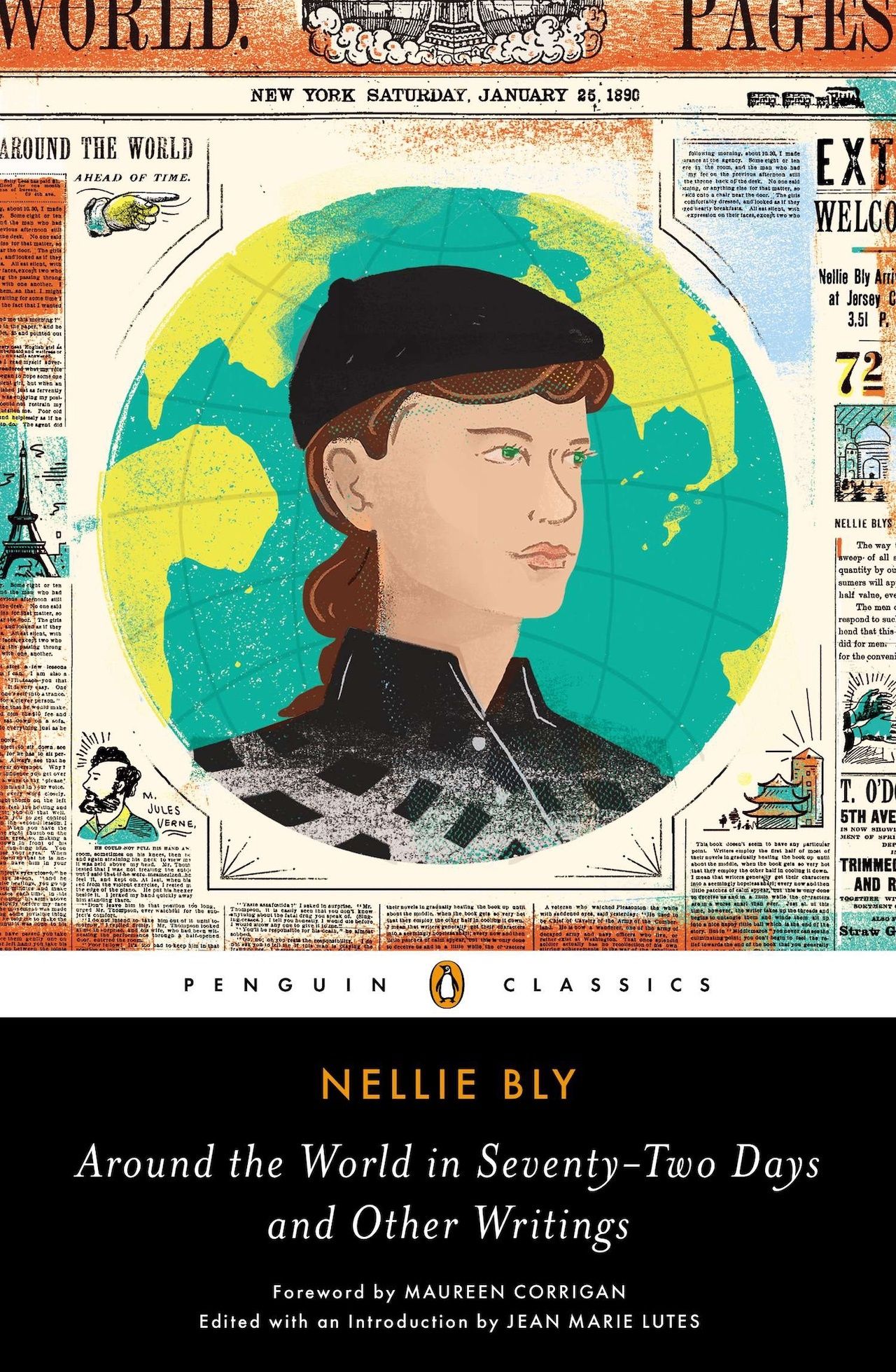

6. Around The World in Seventy-Two Days by Nellie Bly

Photo: Penguin Random House

Bly was no stranger to immersive writing. In her early 20s, she traveled through Mexico as a foreign news correspondent nearly deported for her critical coverage of the government. Back in the States, the journalist went undercover in a mental asylum to document the horrible conditions of patients.

Then in 1888, Bly took on an assignment for the New York World newspaper that would prove her mettle in the male-dominated industry: Mimicking Jules Verne’s adventure in the book Around The World in 80 Days, she would circumnavigate the globe in fewer than 75 days. Allowed to carry only a small bag, Bly journeyed some 24,890 miles and arrived in New York City in just 72 days — a world record at that time.

While Bly’s reports from the trip may seem a bit sensationalized to modern readers, they fit the expressive reporting style of her era. She is not afraid to question colonial authority in the countries she passes through, and it’s clear that Bly believes in speaking out for the downtrodden. Her refusal to write about typical female topics made her one of the most memorable journalists of that era.

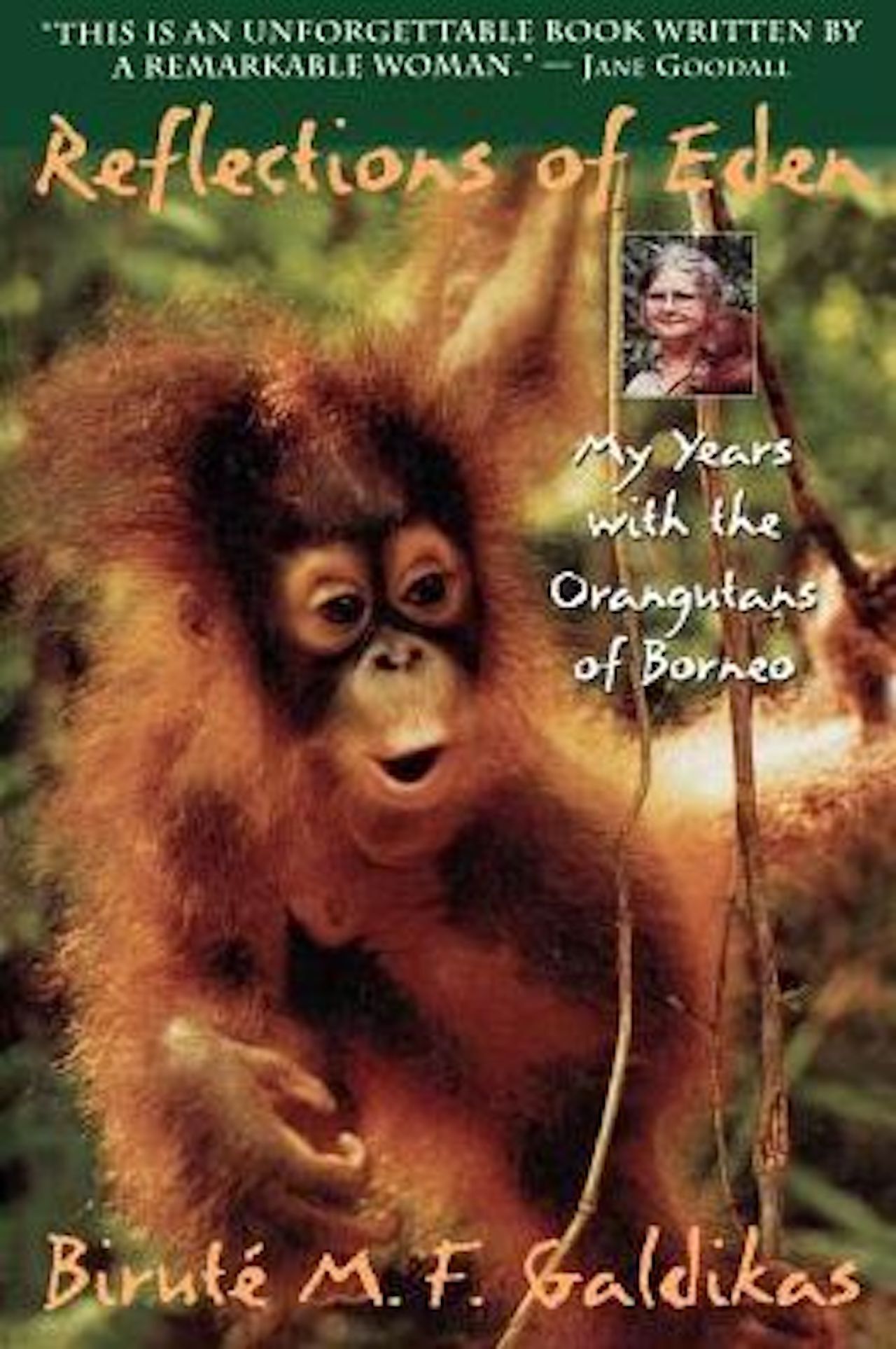

7. Reflections of Eden: My Years With The Orangutans of Borneo by Birtué Galdikas

Photo: Hachette Book Group

Borneo’s rainforests — the only natural habitat of the orangutan — have changed dramatically since Goldikas first arrived in 1971 to study and rescue captured primates. Establishing a base in Indonesia’s Tanjung Puting National Park, Goldikas sets out to study and save orangutans from capture for zoos and private homes.

Her book begins with those first days in the field when she was just a protégé of Louis Leaky (along with famed primatologists Jane Goodall and Diane Fossey) and not yet the world’s recognized authority on orangutans.

Reflections is scientific yet personal, portraying an intense motherly devotion to the creatures she shares an environment with. When writing of her own human relationships, Goldikas demonstrates why she chose her orange-haired neighbors over more traditional family obligations.

It’s a radical example of dedication and brought a powerful voice to conservation advocacy.