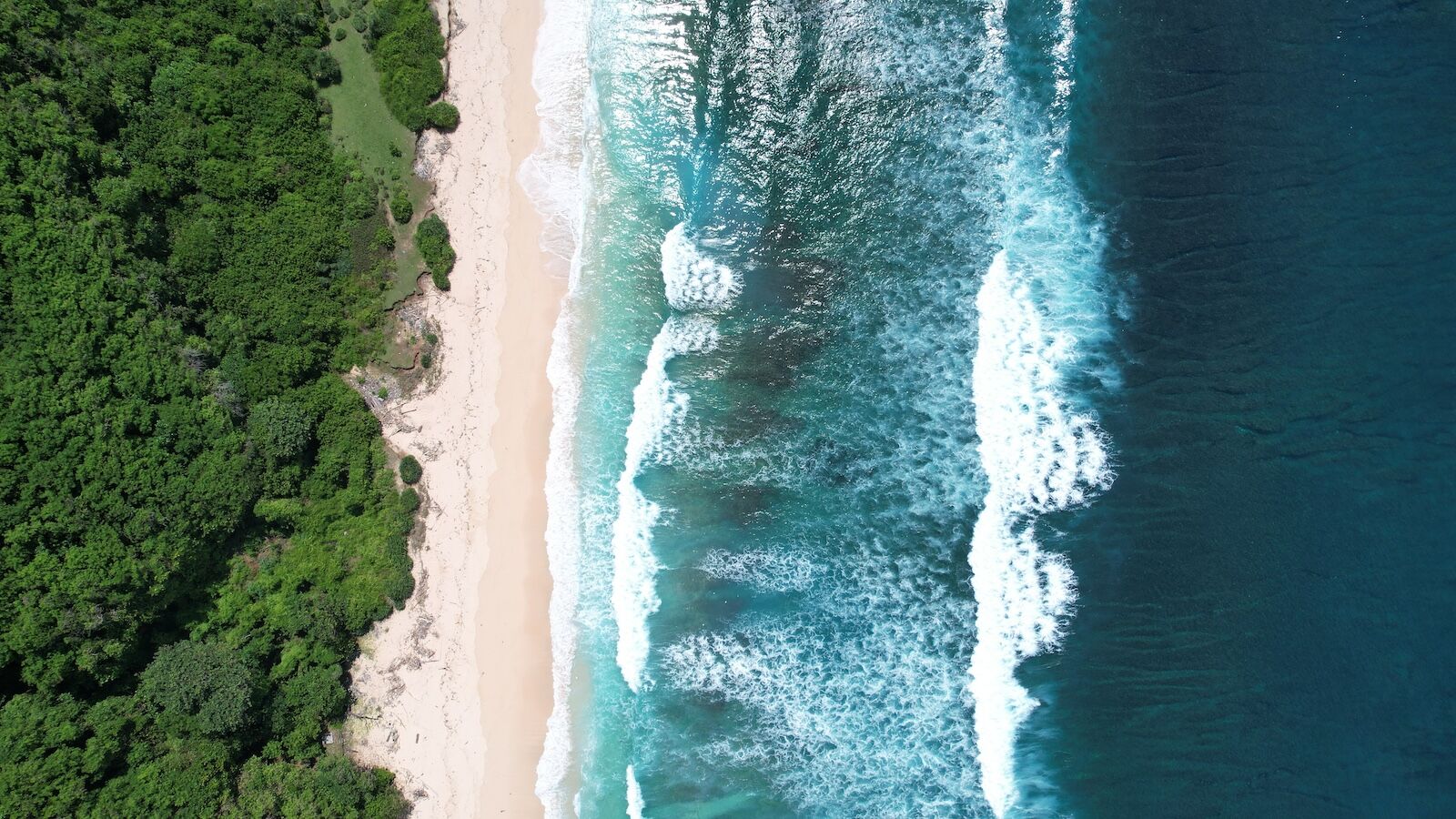

To reach the wave at Uluwatu on the Indonesian island of Bali, you trek down a steep, pale limestone cliff, surfboard tucked under your arm, until you come upon a cave. If the tide is high, the cave will be full of sloshing water. At low and medium tide, the cavity is easier to traverse. You exit onto a sandy cove and look out onto the pulsing azure waves.

Rushed Construction, a Seawall, and a 'Road to Nowhere': How One of Bali's Most Famous Surf Breaks May Change Forever

“Walking down the cliff and through the beautiful cave is very spiritual,” says Rizal Tandjung, a Bali local and one of Indonesia’s best known surfers. Add to the scene the Uluwatu Temple, which reigns over the waves from atop a 230-foot-high promontory, and the vibe is serene.

Then there’s the wave itself: a consistently peeling left that seems to go on forever, followed by another and then another. During the April to October dry season, multiple take-off points work in every type of tide.

“Uluwatu is one of the most perfect waves in the world. From 6:30 [AM] to 6:30 [PM], the trade winds are blowing offshore all day,” Tandjung says while describing ideal conditions. Offshore winds hold waves open and allow for a longer ride on the wave face. The wave works whether the swell measures two feet or 20, adds Tandjung. “It’s a big playground … if you travel from all over the world, guaranteed you’re going to score waves.”

The Uluwatu surf break is so magical that it became a “right of passage” for international surfers arriving in Indonesia, says Jason Childs, an Indonesia-based photographer who’s snapped images for dozens of major publications. That wave’s global renown explains why recent events in Uluwatu have shaken the surf community not just in Bali – but well beyond.

“There’s been so much reaction from surfers around the world because it’s such an important wave,” Childs says.

In August, surfers at Uluwatu were shocked to discover bulldozers rasping into the cliffside below the temple, causing massive chunks of limestone to fall into the ocean below, endangering the delicate inner reef.

“They just started working on this project so fast,” Tandjung says. “The surf community freaked out. We started posting stories.”

The Badung Regency government responded to the uproar with a video forecasting the construction of a massive seawall that it says is needed to shore up the cliff and protect Uluwatu Temple. Also known as Para Luhur, the temple has seemed threatened since a crack first appeared in the cliff in 1992.

The temple, which is sacred to the Balinese people, is also a major tourist draw. Three to five thousand people a day visit Para Luhur, drawn by not only the graceful 11th century structure, but also the sweeping ocean vista, plucky monkeys scurrying about, and fire dancers who perform nightly in an adjacent amphitheater.

Everyone I spoke to, from local surfers to international organizers committed to preserving waves, respected the need to preserve the temple. But none could see how the current work would achieve that aim. To build the seawall, a broad road wide enough for trucks has been carved – bizarrely eroding the bluff it’s meant to save. Currently the road quickly ends, leading some who have commented on the construction to call it the “road to nowhere.”

Photo: Cocos.Bounty/Shutterstock

All that surfers can see at the moment is the damage. Englebert Tomasouw, a representative for Chilli Surfboards who lives in Bali, says he and fellow surfers were stunned to see machines “destroying the cliff,” leaving the water murky with limestone dust and driving away the local wildlife like the dugong (a marine mammal related to manatees).

“Dugong are vegan, they eat seaweed. So they just swim close to the temple and even the cave. It’s like a garden for them,” Tomasouw says. “It’s sad. I never saw them anymore after this happened. It just makes all these creatures of the ocean run away.”

Tomasouw also says that the normally sweet scent of offshore wind has been replaced with dust. “In the dry season, it’s fresh, you smell the ocean, it’s beautiful. But now it’s just dusty, everyone’s coughing.”

Waves break – that is, the swell turns into a curl with a lip of whitewater – when they hit a surface, and the nature of that surface affects the kind of wave you get. Sandy bottoms are constantly shifting, so the peak of the wave can change from season to season or even day to day. Reefs offer consistent waves with predictable takeoff points. And an ideal reef can produce an ideal wave, like the one at Uluwatu — so far.

Construction that allows rocks to fall into the ocean changes the surface and impacts the wave. It also endangers wildlife, which damages the reef and alters when and how the wave breaks. The erection of a seawall is also likely to disrupt the natural flow of sand, which can also disturb the waves.

Should the Uluwatu wave, or the waves just south of it, be irreversibly damaged, it wouldn’t be the first time a wave is destroyed with surfers helpless to do anything about it.

In the early 2000s, William Henry was surfing one of his favorite waves on the Portuguese island of Madeira, a place he’d been visiting annually for over a decade, when he saw some construction and learned that a harbor would be built there.

Stunned, Henry campaigned to stop construction. “There was a total ignorance on the island of what made the surfing wave special,’” Henry says. “There was a widespread lack of knowledge from the general public about surfing, and not only what makes a good wave, but the potential economic benefits of having good surf right nearby.”

Henry’s frustration at seeing wave after wave ruined on Madeira inspired him to start the Save the Waves Coalition in 2003 and head it for its first six years. “We were dealing with things in a reactive manner, for the most part, because these types of issues were popping up all over the world,” says Henry of the early days.

Eventually, Save the Waves began working proactively with local communities to set up Surf Protected Area Networks, which use legal measures to protect waves, and World Surfing Reserves. The impetus for the reserves, says Henry, was a conversation with Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard, who asked why there wasn’t a “World Heritage” designation for waves.

“Uluwatu was the first surf discovery in Indonesia. Without Uluwatu, Bali wouldn’t have become the tourist destination that it is today.”

The selling point of wave protection, says Henry, who remains a Save the Waves board member, is the economic benefit that surfing brings. Save the Waves produces financial impact statements to explain to local communities that surfing is good for their economies.

Ericeira, Portugal, for example, became Europe’s first World Surfing Reserve in 2011. At several of the surf breaks, signage about ability levels, shoreside rentals and lessons, restaurants, and other businesses are on par with the amenities found at mountain ski resorts. As Ericeira has become one of Europe’s top surfing destinations, the economic benefits of conserving its surf breaks have been immeasurable.

“You can talk to them about conservation, and most of these political leaders and business leaders … their eyes just glass over,” Henry says. “They don’t really care about conservation. They care about money. And, unfortunately, that’s kind of the language you have to put it in. That’s why we did economic studies.”

Given that Bali’s modern economy grew up with surfing, protecting its most famous wave should be self-evident.

“So now there’s an awful lot of proof that a wave is worth money, and there should be an awful lot of proof on the island of Bali too,” Henry adds. “Uluwatu was the first surf discovery in Indonesia. Without Uluwatu, Bali wouldn’t have become the tourist destination that it is today.”

Echoing the frustration that Henry felt in Madeira, surfboard rep Tomasouw says, “In Bali, we live by tourism … like, a thousand percent is from surfing.” Despite that, however, he’s seen other surf breaks marred by development, like the Nikko, which was wrecked by a seawall built for a new hotel. “They must understand the water movement … so they don’t destroy the wave, the break for surfing.”

It may be that other revenue sources are trying to outcompete surfing. Tandjung has seen his island change profoundly since he was a young surfer walking 45 minutes through roadless jungle just to reach the cliffs of Uluwatu three decades ago. Most recently, he says that expats who were based in Ubud – the ones he says “come to Bali to find themselves in a lost world” – have been taken with Uluwatu. These expats aren’t surfers, but they love the ocean view, and they’ve helped fuel a building boom.

The absence of clear communication from the local government about the Uluwatu project has gotten the rumor mill spinning – with surfers fearing new hotels, roads along the coast, and even a road down to Uluwatu Beach itself, where beachgoers would be charged per visit.

“Everybody [is] kind of guessing what it actually is, because there hasn’t been official plans released besides that one video,” says Emmet Balassone, who coordinates the endangered waves campaign for Save the Waves. “There just hasn’t been a lot of transparency at all around this project.”

Frustration about the lack of information caused local surfers to contact Save the Waves, says Balassone. The foundation has filed a request for an Environmental Impact Assessment, which he says should have been undertaken before beginning construction. “You can do these projects without an [environmental] assessment in Indonesia if it’s for an emergency purpose, but there is no state of emergency that was declared,” says Balassone.

At least the outcry has been somewhat effective, says Balassone, since the Bali Attorney General’s Office is now investigating the Badung Regency and its Building and Public Works Agency to assess potential construction permit and license violations.

Photo: EnthusiasticPhotographers/Shutterstock

That doesn’t halt the construction that has already begun. “What they’re doing now is kind of the worst case scenario. It seems a little overkill with how big the seawall is in that CGI video that the government released, and how far out it goes into the reef,” he says.

At a minimum, whatever construction is going on could be better managed. When Bali was less wealthy, limestone was saved and resold. The construction company should at least be forced to stop the limestone going into the water, says Tomasouw.

“You can’t just go pushing debris and rocks and stuff off of a cliff into the water where, literally, one of Indonesia’s most famous premier surf spots is,” Save the Waves founder Henry says. “It’s nuts.”

For now, surfers remained concerned. Tomasouw says that the old days of palling around with your friends out on the water and commenting on the waves have been replaced with worry. The buzz of the machinery is a constant reminder. “Every time we go there, we just talk about it,” he says. “We surf a few waves, and then we look back at the cliff. We just talk about it.”

William Henry has some advice for the local government. “I guess I would say be careful, because this is a pivotal point in your history. You know, you have decisions to make about how future development is handled on your island, and you need to protect your resources. And surfing is one of your greatest resources.”