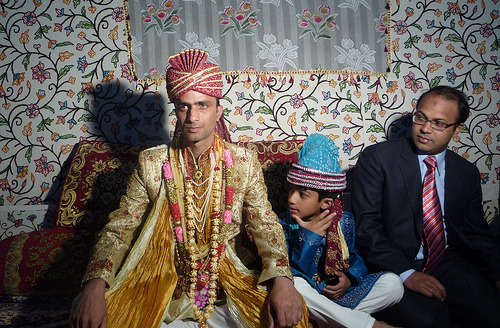

All photos by author

SRINAGAR IS THE MUSLIM-dominated capital of Kashmir, India’s northernmost state. Resting in a valley between snow-capped Himalayas whose peaks are visible even on cloudy days, local tourist paraphernalia boasts that the city is “Paradise on Earth.”

Kashmir has been the center of periodic fighting between Pakistan and India since the 1947 partition, as both countries claim ownership over the state. Beautiful as it is, it is also highly volatile and prone to civil tensions that range from localized to crippling.