Born into wealth in 1830 as the eldest daughter of an English member of parliament, like many upper class women of the time, Marianne North devoted herself to painting flowers. Unlike other Victorian women, though, North could not be satiated by roses. At age 40, she set off alone to travel the world, braving rough ship and living conditions to document over 900 plant species in just 14 years. She has four plant species named after her.

Marianne North: The Victorian Gentlewoman Who Documented 900 Plant Species

It helped, of course, that she was both rich and single. Financially independent following the death of her father, North used her spinster status and the freedom it allowed her to her advantage when she embarked on the first of many far-flung trips to paint the world’s flowers. “Marriage? A terrible experiment,” she once wrote.

North’s great journey started in 1871 with a trip to Canada, the US, and Jamaica. She then moved on to Brazil where she bushwhacked through the Amazon for eight months to paint its as yet undiscovered flora. Over the next 13 years of travel—an odyssey that would take her around the world twice over—North would discover numerous plants.

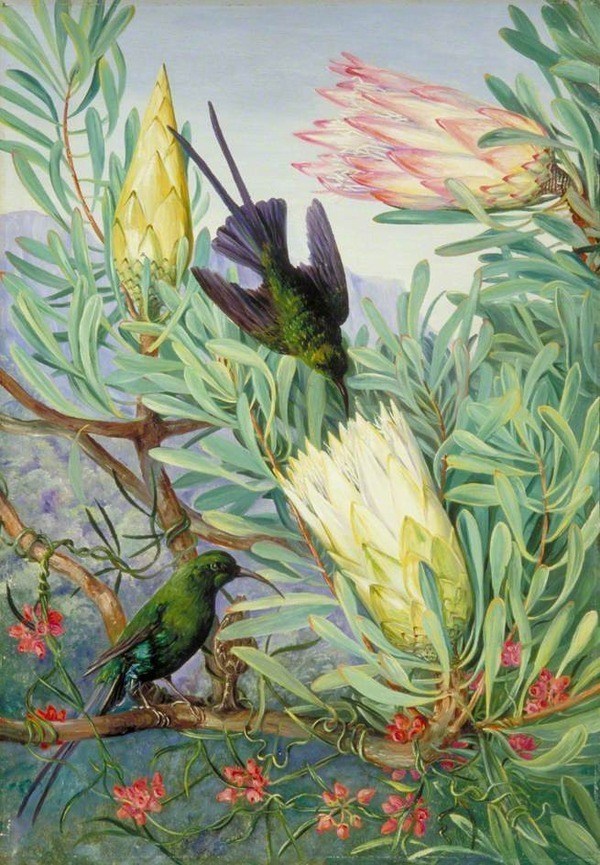

“Honeyflowers and Honeysuckers” (1882), South Africa (via WikiPaintings)

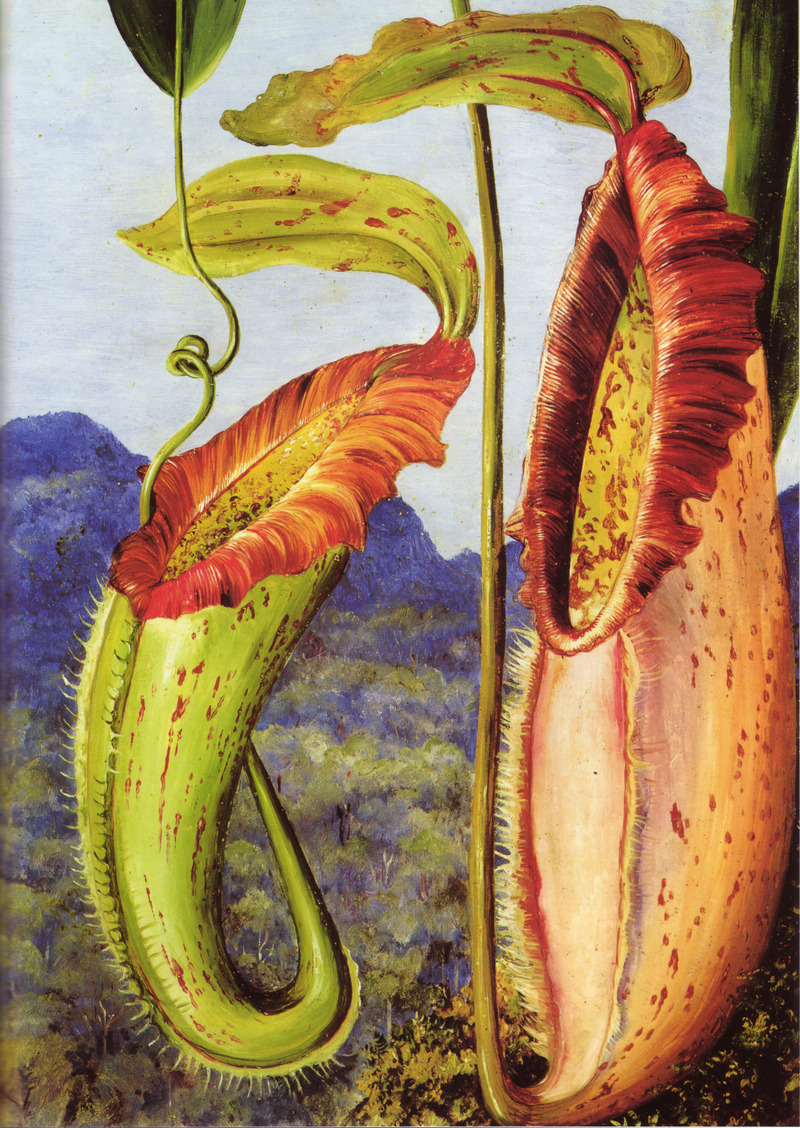

But unlike most male naturalists of the time, she didn’t stuff rare flowers in her suitcase to show off back home. She simply painted what she saw with a scientific accuracy that would make her paintings vital botanical records. And by eschewing ‘ladylike’ watercolors for oil paints — all the better for capturing the rich colors of the tropics with — and painting flora in their immediate environment rather than as individual plants against a white background, North’s style was unique.

Marianne North knew how to live: Wherever she was in the world, her days would begin at dawn when she would take her tea outside to watch the world awaken. She would then paint frantically outdoors till noon, consumed in what to her was “a vice like dram-drinking, almost impossible to leave off once it gets possession of one.”

Rainy afternoons were spent painting indoors, while evenings were given over to exploring outdoors and returning home well after dark. Her life, as she described it, was one of “wander and wonder and paint!”

North may have been privileged — her family name granted her letters of introduction to ambassadors, viceroys, and rajahs all over the world; she even traveled to Australia on the personal recommendation of Charles Darwin — but by traveling mostly alone (she found company tiresome) and battling her way through hostile terrain, often on rickety transport, there’s no doubt that Marianne was an adventurer.

Marianne North (courtesy A McRobb/RBG Kew)

Despite her connections, North preferred a simple life: Rather than travel with trunks full of clothes to serve her well at colonial soirees, North’s entire wardrobe could be contained in one small suitcase. In fact, the thought of having to appear at formal dinners in sticky evening dress was akin to torture for her, and she wrote to her sister from Jamaica: “These unthinking croqueting-badminton young ladies always aggravated me and I could hardly be civil to them.”

In 1882, a gallery of North’s work opened at England’s Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. Funded by North at a time when photos were still in black and white, North’s paintings provided the scientists at Kew and the general public an intriguing glimpse of the world beyond Europe.

With her health failing, no doubt as a result of the harsh conditions she endured during her travels, North died at home in Gloucestershire in 1890. She was 59.

Over 130 years later, North’s 832 paintings are still on show in the same tightly packed formation—like a giant postage stamp album—as when the gallery first opened. The only permanent space dedicated to a single female artist’s works in Britain, the Marianne North Gallery is also one of the most important collections of botanical art in the world.

The Marianne North Gallery at Kew Gardens. (Photograph via Wikipedia Commons)

Pitcher plants of Borneo (1876) (via Wikimedia)

As first published in Atlas Obscura