IN THE EARLY STIRRINGS OF THE SECOND IVORIAN CIVIL WAR in February 2011, Aboudia Abdoulaye Diarrassouba escaped from his apartment in Abobo to the home of his agent Stefan Meisel in the Abidjan neighborhood of Riviera Golf. On March 30, 2011, the battle for Abidjan erupted. The young Ivorian painter was confined to the workshop at Stefan’s house for 10 days.

During the day, Aboudia worked in the garage only 12 meters from the havoc in the streets of Abidjan. In between lulls in the fighting, he would look over the walls. He saw bodies scattered in the streets. The bodies were given a few days’ grace, and then tires were placed atop them and set alight. When wood and garbage were added, the thick, pungent smoke would eventually dissipate. The remaining ashes were scattered into the bushes or swept into the drain.

He painted what he saw: “the everyday, my environment, my context.”

When Aboudia ran out of supplies, he mixed his remaining paints or scavenged for materials. When he ventured outside 10 days later, he had completed 30 paintings.

After ten years of civil war, expats become patrons of the arts in Côte d’Ivoire

My boyfriend Manu and I live in Riviera Golf, around the corner from Aboudia. We moved here from Toronto in January to pursue new careers: He works for an organization that assists entrepreneurs in building sustainable businesses; I am focusing on freelance writing.

When we first arrived, I could only see the remnants of war: the blackened buildings, the armed soldiers, the iron grids on doors.

A month later, I made an effort to pay more attention to my environment and less attention to the context I had read so much about. I could see the half-finished frames of houses were acquiring bricks and mortar; fences had sprung up and next to them, rickety tables teeming with mangoes, pineapples, and cloudy bottles of kola nuts.

And yet what Aboudia saw last year happened only five minutes from where we live.

In the years following independence in 1960, Côte d’Ivoire was a model of stability for West Africa under the presidency of Félix Houphouët-Boigny, who reigned for 33 years in relative peace. Houphouët-Boigny was instrumental in campaigning for the country’s independence, but encouraged French technicians to stay and develop Côte d’Ivoire.

By 1978, Côte d’Ivoire had succeeded Ghana as the world’s top cocoa producer and exporter. President Houphouët-Boigny encouraged immigration to fulfill the global demand for cocoa. Citizens from neighboring countries like Mali, Burkina Faso, and Guinea were lured by Côte d’Ivoire’s economic prosperity; by 1980, 26% of the of the population was foreign. Two years later, the income from exports doubled.

But the economic boon was short lived — a world recession, drought, and a drop in international cocoa and coffee prices sunk the country into economic crisis. Tensions increased in part because of the millions of Burknabés living in Côte d’Ivoire seeking jobs. “Native” Ivorians resented the immigrants whom they now accused of stealing their livelihoods. Following Houphouët-Boigny’s death in 1993, the country began to degenerate into chaos.

Tensions between Ivorians and immigrants erupted into the first Ivorian Civil War in 2002. The war broke out between the forces of President Laurent Gbagbo — who fanned the country’s xenophobic flames against his rival, Alassane Ouattara, a Muslim from the country’s north whose Ivorian heritage was being questioned — and the Forces Nouvelles de Côte D’Ivoire, representing Muslim northerners who supported Ouattara and felt they’d been marginalized by the Christian southerners.

The war ended in 2004, but French and UN peacekeepers continued to patrol the zone that separated the rebel-held north from the government-controlled south. Elections were continually delayed by Gbagbo and the country’s general unsettledness, and weren’t held until 2010, five years after Gbagbo’s term should have ended. Then, Gbagbo refused to concede defeat to Ouattara, and the Second Ivorian Civil War began, killing more than 3,000 people.

During this decade of conflict, many companies closed or relocated, leading to massive job losses. As of November 30, 2011, the World Bank said that four million young men were unemployed in a country of 21 million.

For the artists of Côte d’Ivoire, the civil war damaged an infrastructure that had few support mechanisms for them to begin with; even in less volatile times, artists were hard-pressed to earn a living with the twin burdens of ten years of conflict and dwindling foreign investment (in the form of tourists and patrons).

Last July, the Minister of Culture and Francophonie, Maurice Bandama, said the government’s upcoming projects, which included festivals and a centralized database of arts and culture venues, would ignite a cultural renaissance in Côte d’Ivoire: “[It’s about] deploying all artists, filmmakers, painters to help healing and social cohesion,” he said. “Our work [is to make] this sector profitable.”

The tagline for the ministry is, “Art and culture will reconcile us.”

But Bandama admitted there had been challenges in restoring the infrastructure due to pillaging — even the Palace of Culture closed for weeks in the wake of the 2010 election. Its rehabilitation was symbolic of the country’s desire to move forward.

Still, a contemporary art scene needs more than a revamped venue to thrive — it must establish an industry to market its works, a place with galleries and collectors, critics and a devoted public. Above all, a burgeoning contemporary art scene needs continuity.

There are some Ivorians championing the cause of contemporary artists in Côte d’Ivoire: Simone Guirandou-N’Diaye, the commissioner of the first International Exhibition of Visual Arts, held at the Palace of Culture last December, in which 50 local artists and 15 foreign artists participated; Augustin Kassi, born in Abidjan, who founded the Biennial of Naive Art in 1998, and uses the festival as a platform for promoting other West African artist; and Illa Donwahi, who created the Charles Donwahi Foundation of the Arts in 2008 to respond to the inadequate (or absent) distribution channels, museums, and galleries for up-and-coming artists. The foundation includes three villas, two apartments, and an artists’ residence.

There are also local art collectives, but these groups do not generate the funds necessary to make the artists self-sustaining, although they do provide a support system and a sense of solidarity. Uniting them with other like-minded groups outside of the country is a Herculean task in itself. The dearth of centralized databases and the remote locations of some of the artists can make meetings impossible. A public database would enable artists to easily reach interested buyers, peers, and gallery owners and would facilitate get-togethers for exhibitions, gallery openings, and festivals.

Indeed, most emerging artists in Côte d’Ivoire lack the connections with the global art community that might allow them to monetize their talents. And so expatriates have become invested in revitalizing the country’s contemporary art scene by aligning themselves with Ivorian art collectors, critics, and aficionados in order to become patrons of the arts.

The rise of an Ivorian artist

A gaunt rabbit scrabbled behind Aboudia’s latest canvas, which sat under a corrugated roof in agent Stefan Meisel’s garage. When Aboudia moved in with Stefan, he brought two white rabbits — now Stefan considers them to be “our pets in our workspace.”

Stefan and I were sitting on the terrace. The rabbit nipped at my fingers when I reached for my glass of water. Its eyes were glossy and pink-rimmed; a clump of blue acrylic paint was embedded in its fur.

Five years ago, Stefan “met a girl” and followed her to Abidjan from Berlin. The city suits him, with his relaxed attire and even more relaxed demeanor. His pinstriped shirt was untucked, his hair in a loose ponytail. He was smoking his third cigarette of the day.

Once, Stefan was an artist in his own right, but as he candidly put it, he quit because he realized he would never be a “high-level artist.” Among his other professions, he has held the coveted position of photographer for Côte d’Ivoire’s football team, Les Éléphants, and overseen the production of the country’s telephone book. He is now the agent of several up-and-coming Ivorian artists.

“After the first revolution in the end of the nineties and then the second last year, the Ivory Coast became a little bit of a culture vacuum,” said Stefan. “But it has changed right now with the Internet and influences from outside.”

Stefan discovered Aboudia through Facebook when he saw Aboudia’s paintings on a friend’s page. He visited Aboudia’s studio in the district of Abobo and agreed to pay Aboudia a monthly sum of 300,000 CFA ($570 USD) — half for his painting materials, the other half for his living expenses. (Stefan told me that Aboudia spent most of the money on the materials.)

Aboudia was born in Abengourou, a small town about 240km from Abidjan. When he told his parents he wanted to become an artist, his father threw him out of the house, but his mother gave him her savings (15,000 CFA, about $30 USD) to compete for a scholarship in Abidjan. He secured the scholarship, but had to sleep in his classroom because he had nowhere to live. In the mornings, he would pretend that he had just come “from a home I did not have.”

In December 2010, as tensions were flaring and there were sporadic outbursts of violence in Abidjan, Aboudia moved into a 10m2 studio without a shower or toilet, with only four paintings to his name.

He lived near Abobogare, the railway station in one of Abidjan’s most densely populated neighborhoods. The area has long been a refuge for migrants and other impoverished people. He became inspired by children’s graffiti on public walls, how the children used charcoal to scrawl pictures of cars, televisions, and other status symbols.

“Children became my role model: the weakest, not taken seriously, shunned, alone in their world,” Aboudia said.

Aboudia refers to his artistic style as “nouchi,” the urban slang spoken by young people in Abidjan.

“It’s a children’s style — like graffiti that you find in the street. It’s like it’s them passing a message through me.”

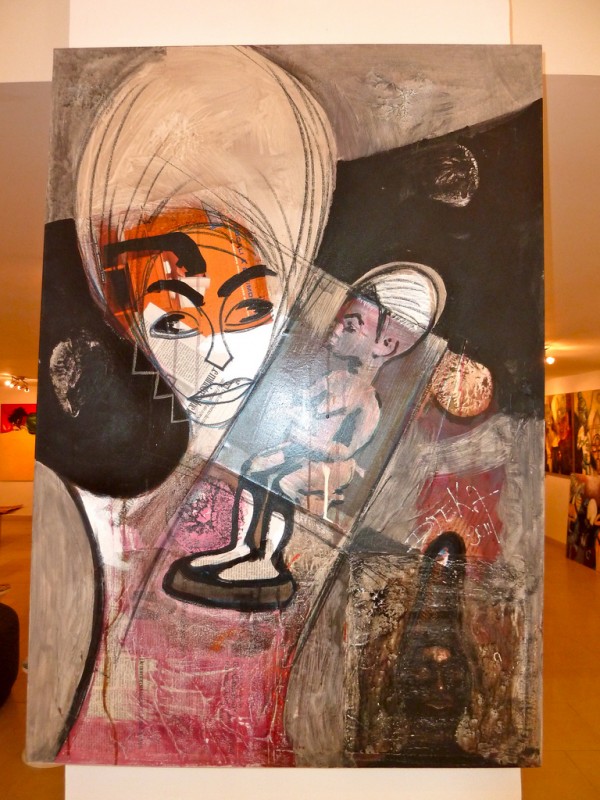

Aboudia layers meaning into his paintings by using recycled items such as cigarette papers, empty cement sacks, and flattened “Afrika” matchstick boxes. In the open garage, there is a bookcase packed with found objects: comics, cigarette papers, picture books, magazine covers, dictionaries…

The first step in the artistic process is to layer a collage on canvas. In one painting, a Moulin Rouge poster peeks from beneath smudges of gray chalk: “Discover…the most famous cabaret in the world.” In another, the photograph of an African warrior is outlined in black acrylic, his features erased by paint.

In the second step, Aboudia adds acrylic paints and then finishes off the canvas with pigment crayons and Kaolin, soft clay rubbed on the skin of participants in traditional ceremonies. He has even used instant coffee to get the right shade of brown. The final step is the addition of text or numbers. The title is usually incorporated into his artwork: “Election poison,” “ONUCI” (the UN mission in Cote d’Ivoire), “Interdit d’uriner” (Urinating is forbidden here.)

The early paintings are mostly in earth tones and pastels. The children are stick figures, surrounded by the reassuring words of family figures — “A kiss, Maman” — and the faces have a softness to them, the oval heads and rounded eyes and mouths suggesting innocence.

The painting “Don’t piss – gets you in trouble” was made in 2010 before children were under the threat of civil war. The words “fine” and “palabre” (another word for a quarrel) hang in the air. The painting recalls an era when police had the time to deal with petty misdeeds.

Aboudia did not have the $0.95 USD to take the train, so he would walk 30km into downtown Abidjan to show his paintings to the gallery owners. His work was often rejected because it did not reflect traditional African art in terms of technique or content.

Historically, Westerners have insisted on ethnic identification for African art; they believe it should reflect “traditional culture”: an association with magic or witchcraft, the depiction of African animals like lions and antelopes, the use of natural colors and indigenous materials (like the gold sculptures in Ghana or the wood carvings made by the Baulé people from the trees that line the Ivorian coastline).

With the Internet and increasing globalization, Ivorian art is starting to incorporate Western techniques and ideas. Tradition is being imagined in different ways, and classic uses of form and color are being cast aside. Ivorian artists are striving to be recognized as individuals rather than entities that represent regions — or the whole continent — of Africa.

“There are a lot of artists working in a traditional African style and some who are copying famous Western styles and giving them an ‘African touch.’ But there are only a few who have an identity, an individual style,” Aboudia said. “You know, we know each other, we are doing sometimes one of the few group exhibitions the year over together, but that’s it. I’m used to being alone, working alone…that most other artists don’t like or don’t understand my work.”

When Aboudia eventually sold his first paintings, he said his customers were “the whites, ambassadors [and] gallery owners in other countries.”

Last February, Aboudia’s canvases became bigger, busier, and darker, with ghostly and skeletal bodies and scarlet paint. They have a nightmarish aspect to them with mouths that gape, teeth resembling headstones, and harsh, right-angled jaw lines and temples.

Aboudia has been compared to Jean-Michel Basquiat, the Haiti-born painter who began his career as a graffiti artist in New York City. Aboudia has adopted some of Basquiat’s techniques: the spontaneous brushstrokes, the boxy skulls and bared teeth, the combination of text, media, and codes — logos, words, letters, numbers, pictograms. (Aboudia painted “Hommage to Basquiat” in which a silhouette of the New Yorker’s iconic dreadlocks takes center stage.)

One of Aboudia’s most famous paintings of the civil war was “Invisible Commando,” in which a soldier is shown shooting a policeman. Stefan said it was dangerous to show this picture during the conflict.

The “Invisible Commando” was the nickname of staff sergeant Ibrahim Coulibaly. In January 2011, Coulibaly was the head of a militia group that supported President-elect Ouattara. He lived in Aboudia’s former neighborhood, Abobo, where his militia led a series of surprise raids against pro-Gbagbo forces. When Gbagbo was deposed, President Ouattara began operations to disarm militias on both sides, but Coulibaly refused to abandon his arms and was killed in a shootout on April 27, 2011.

Camouflage colors dominate the painting, except for an incandescent United Nations Operations in Cote d’Ivoire (ONUCI) vehicle in the background. A “Vote Gbagbo” poster bleeds through the right-hand corner of the canvas, showing the confident former president saluting the public.

The darkness of the period is palpable in all of Aboudia’s paintings during the war. The layering of torn images mimics the brutality of Aboudia’s environment, ripped asunder by soldiers and shelling. The flurry of numbers and letters in the background add to the confusion; people become distorted through the lens of civil war. One glimpses bandaged heads and faces with the eyes gouged out.

The paintings inspired by the civil war brought Aboudia to the public’s attention. After considerable international media coverage, gallery owner Jack Bell held the Ivorian painter’s first exhibition last summer in London. Now Aboudia is able to live comfortably off his earnings.

“[The conflict] is what people are interested in — and it opens the door. But because he was recognized in the world for his war paintings, that doesn’t mean that the paintings before that were…less,” Stefan said. “But he was the first artist to paint the documentary on the conflict.”

And Aboudia does not see himself as just a “war painter.”

“Conflicts are a part of life, like other positive things as well. My role is to observe and paint. If I can’t do that, then I’m lost,” he said. “If it can help people remember what happened these past months, that’s good, but above all I painted these works for myself.”

As Stefan said, “He paints because he has to paint.”

Ivorian artists resent being defined by the conflict — they just want to put it behind them. Western media tends to concentrate on the most miserable aspects of West Africa: civil war, poverty, AIDS. Ivorian artists want their artwork to be appreciated for its own merits rather than the circumstances in which it was made.

“The war and the crisis preceding it were an episode that I documented, no more and no less. Today I [have] put away my war paint brushes, and I’m once again painting people’s small, everyday joys,” he said. “I’ve started going back to see the children of Abobogare.”

And Stefan is in the process of launching the first online gallery of Ivorian contemporary art in October 2012; it represents his current roster of clients, including Aboudia and the sculptor Camara Demba. He has named the website Abobogare.com.

Traveling between the shores of Europe and Africa

Virginia Ryan and Yubah Sanogo work in the Cocody neighbourhood of Abidjan. Virginia is an Australian-born artist married to the Italian Ambassador to Côte d’Ivoire; her residence houses an art studio, where Yubah, a native Ivorian of Senufo (an ethnic group in northern Côte d’Ivoire) descent, has been her assistant for three years. Yubah commutes between his home in the city of Bingerville and Abidjan.

When I arrived at the Italian Embassy, the guards requested a piece of identification, gave me a quick once-over, and opened the gate. I was early and Yubah had stepped out for lunch. One of the servants took me to the back veranda where I had a view of a terraced, verdant garden and an azure pool, where two bodyguards were sunbathing.

When Yubah rounded the corner of the house, he was wearing the iconic painter’s jeans and a striped golf shirt. We descended the steps of the veranda and headed left to the workspace.

The studio had two covered areas. One was carpeted in artificial turf for sculptures, like the giant mermaid’s tail made of black hair extensions. There was also a smaller version of the mermaid tail, made of wire, twists of plastic thread, and plastic dolls’ heads, bleached white — they looked like sun-battered shells. Virginia and Yubah retrieved these items from the shoreline of the Ébrié Lagoon, where Abidjan is situated.

During last year’s war, Yubah commuted between his own workspace in Bingerville and the workspace he shares with Virginia at the Italian Embassy residence. At the height of the crisis in April 2011, he was unable to leave the embassy residence, but this allowed him to work continuously. He told me that he painted images that were “dark and full of sadness and peace” as gunfire rattled around him. To illustrate the point, he showed me a crack in one of the walls, where a bullet had ricocheted.

The situation in Bingerville was worse. While Yubah was painting there, blood spattered onto his canvas when a bullet grazed a woman who was walking by with her child.

“I left the wound [on the canvas] to say ‘never again,’” he said. “It pushed me to work harder; it pushes who I am and what I paint.”

He carefully peeled the plastic from an intricate set of mermaid heads he had made with Virginia for The Spirit of the Water exhibition in November, 2011. He unearthed papier-mâché objects adorned with detritus from the shore — shells, dolls’ limbs, and toy soldiers. They had a tangle of hair extensions and marbles for eyes. Abandoned items that wash ashore are a recurring theme in Virginia’s artwork and have seeped into Yubah’s work, too.

The Spirit of the Water, Virginia’s exhibition, was inspired by the idea that mythologies travel between countries and are literally swept ashore. Virginia identified the mermaid as a key “mythology-carrier” between Europeans and Africans for centuries.

In January 2010, Virginia asked artists in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana to create works inspired by this mermaid theme. With the support of the Charles Donwahi Foundation for Contemporary Art, the exhibition opened on November 25, 2011, with 50 works, as the crisis was starting to escalate. The artists had realized the mermaid theme in everything from traditional batik to bronze and plaster.

Yubah produced a cube called “La Mère de la Mer” (The Mother of the Sea). Each side of the cube is awash in pale blues; on one side, rope has been stitched into the canvas to create a mermaid’s tail and flowing locks of hair. It now sits in Virginia’s living room — one of many pieces she has purchased since she arrived in Côte d’Ivoire in January, 2010.

One of Stefan’s clients, Camara Demba, created a sculpture entitled “Mamiwata meets Manga”; his mermaid has a garish, yellow crown, gray tail, and dark green torso. Abidjan-born Salif Youssouf Diabagaté painted a tragic, entrapped mermaid onto the surface of re-used postal bags, entitled “Vision of Mami Wata.” Dramane Quattara, a sculptor from Grand-Bassam, Côte d’Ivoire, created two writhing mermaids cast in bronze, each head bound to the other’s tail.

There was also a blank papier-mâché mermaid’s tail with the word “peace” on it suspended from the ceiling. The artists invited attendees to write their comments on it in any language. It became the ultimate collective work — a piece of art that was conceived in the venue and could only be completed by other people’s words.

By early December, 2010, the exhibition was cancelled due to the war. Virginia marveled at how hopeful people were at The Spirit of Water exhibition — only a few months before the city fell apart.

But these were not unfamiliar circumstances. The conflict in Côte d’Ivoire triggered memories of the trauma Virginia had experienced “thirdhand” in Belgrade in the early 1990s. During that civil war, she devised ways to “move out of her own skin as an artist and imagine other ways of making art with people during or after situations like that.”

Constant movement has characterized much of Virginia’s life. She has lived in Ghana, Egypt, Brazil, and ex-Yugoslavia.

“But rather than that becoming a kind of misplacement…the experience of displacement feeds into my work totally,” she said. “I am always trying to create some kind of stability amidst experiences of movement.”

When she and her husband moved to Edinburgh, Scotland, she completed a diploma in art therapy. It reinforced her desire to connect with other groups of artists. For her, this gathering of people is part of the process of healing and also a way to help emerging artists. Indeed, what kept her “artist friends” in Abidjan going during last year’s war was the knowledge that their fellow artists also continued working.

“I think that it’s extremely valuable that artists keep on doing their work…it is a sign that there is some sort of social cohesion,” she said.

“Art [is always] connected to social action. Even if I’m in my own room doing something that seems divorced from the rest of the world, it’s not…. On that level, I think that [art] is valuable in itself — you do not need [it] for other reasons.”

Virginia would like to establish a foundation similar to the one she founded in Ghana in 2004, created to provide an active network for artists and to develop the contemporary art in Ghana. It has grown to 100 members.

It has been a little harder to create that social cohesion in Abidjan, but Virginia has had some success in promoting Ivorian artists. She spearheaded a group called Abidjan Anglophone Art Safaris. It is described as being “for lovers of West African art — in English” and gives expatriates the opportunity to learn about contemporary art and engage with young Ivorian artists.

The art safaris are about double exposure: Art aficionados are exposed to West African art and the artists to a wider audience and potential buyers. Indeed, duality often crops up in the contemporary art scene in Côte d’Ivoire, whether it is about the fusion of two cultures or of classic and modern techniques.

The relationship between expatriate and artist is not one-sided. Interacting with West African artists has altered Virginia’s art, from its themes to the recycled materials she uses. In many ways, Virginia is who she purports to be studying — a woman who travels between the shores of Europe and Africa.

When discarded items are rescued, they become multi-faceted: practical and environmentally friendly, because the rubbish becomes art; timeless, because they get a second life as they migrate from one shore to another, then from their found environments to the artist’s canvas. They also become artifacts imbued with history each time they are retrieved from the shore.

When Virginia went to Accra, she lugged all of her expensive art supplies, but she felt guilty using them when nobody else could afford them. She observed how creative Ghanaian artists were in using what was around them and adopted their philosophy.

In the traditional art of Côte d’Ivoire, function is prized over form. It is not so much about the beauty of the object, but the purpose it serves. Although Westerners tend to appreciate art for its own sake, West African art has historically been bound to its variable uses rather than its aesthetic value. For example, a mask may represent ancestors or powerful spirits, and it facilitates communication between people and supernatural beings. Other objects are made in the form of human and animal figures; they are used to ward off the evils of disease, natural disasters, or infertility.

Historically, the object must be useful before it can be rendered beautiful; its beauty is simply part of its function. For this reason, discarded items had little value and were perceived as useless or obsolete. But Virginia has helped remove that stigmatization for Yubah, who now uses them regularly in his art.

“If you recycle an object and breathe new life into it, in a sense it’s about hope and regeneration — and that is what people need to feel after a big slashing wound like a war,” Virginia said.

Yubah’s use of recycled materials not only reflects a contemporary art movement, but also encourages other artists to use readily available, cost-effective items for their art — and to imagine different uses for these objects: Chicken wire can be molded into jewelry; butterfly wings are sewn to make a tapestry; empty canisters become a drum set. And they become, in effect, symbols of the country’s renewal post civil war.

In 2010, Yubah started working with Terre des Hommes, an organization that runs an informal education program for slum children in southeastern Côte d’Ivoire. He collaborated with these children on a sculpture made from recycled farm materials. They also helped him recover bags of water from the streets, and tattered leaves and discarded necklaces and shoes from the shore. The final product was coated in white paint and decorated with a smattering of black stars. The purpose of the sculpture was to prove to these children that being an artist was not outside their means.

Yubah is also the president of a local collective, the Young Artists Association in Bingerville, which provides young artists with support and mentoring after they finish school.

“[Before] when artists finished school, they had no direction,” he said. “So we decided to work together to bring these students back into contact with [more experienced artists] to improve their technical and professional skills. We want to work with all the visual artists in Côte d’Ivoire and other artists [in Africa].”

There is no membership fee; instead, each of the 50 artists must contribute a painting for an exhibition that they hope will generate funds for the association’s needs, which range from painting materials to workspace.

During last year’s war, the artists of Bingerville collaborated to ensure they were able to continue making art by sharing workspaces and supplies — and showed their solidarity by continuing to work during the crisis.

In Yubah’s case, his artwork affirmed another fact: In embracing Ivorian and European techniques, he effectively becomes a conduit linking the contemporary Ivorian art scene to the global one.

“I make a mixture [of the art forms], because as I become more familiar with the world, I want each person to find themselves in my work, in my paintings,” he said.

Feet in tradition, head in modernism

Galerie LeLab is an artists’ collective in the Abidjan expat district of Zone 3, run by a Frenchman, Thierry Fieux. Fieux launched LeLab to promote and sell the work of contemporary Ivorian artists. He also is invested in training them about current practices in the visual arts to make them more competitive on the world stage. Currently, LeLab is exhibiting the works of six artists.

Taking to heart the Minister of Culture and Francophonie’s assertion that festivals are the bedrock of any culture, Thierry launched the International Visual Arts Festival of Abidjan in 2007.

It is a multidisciplinary festival, which features paintings, sculpture, photography, and a symposium, among other things. Its goal is to unite artists from Europe, America, Asia, and Africa around the topic of art and development. It also highlights emerging artists who display their artwork for viewing and sale at Galerie LeLab. The festival occurs over three weeks at the gallery, the Charles DONWAHI Foundation for Contemporary Art, and other artistic venues in Côte d’Ivoire.

Like Stefan’s roster of artists, most of Thierry’s artists are young Ivorian men seeking to make a living from their art. There is a distinct lack of female Ivorian artists. Historically, women have been excluded from the fine art world; gender bias is still strong today in Côte d’Ivoire and the idea persists that a woman’s place is in the home, where they can rear children and tend to housework.

One of Thierry’s emerging artists is Djeka Kouadio Jean-Baptiste, who exhibits regularly at Galerie Lelab and was Aboudia’s assistant for the art workshop this February. Like Yubah, Djeka works out of his home in Bingerville.

The thirty-year-old painter was born in Bouaké, the second largest city in Côte d’Ivoire. He has a strong connection to his Ivorian heritage and laments the fact that his ancestors are “intellectuals who have been forgotten.” In his compositions, he draws out symbols of three-dimensional objects like masks, statues, figurines, and scales for weighing Akan gold.

Djeka has distinguished himself as an artist by using an impasto technique to represent the links between people, their cultural values, and the universe. The technique is called “couler,” where he lets several colors flow together on his canvas. His brushstrokes create movement and tension in his paintings. The thickness of the paint and his use of geometric symbols and patterns make the paintings appear three-dimensional. He sometimes layers images over newsprint — a technique also used by Aboudia. He re-imagines traditional images and uses modern techniques to translate them to his canvas.

Djeka said that he focuses on esoteric, African heritage in his artwork. He wants the observer to ponder the spiritual and historical dimensions of his paintings. He pays tribute to his ancestors (“because we are the present people of a past generation”), but also wants to challenge their concept of Ivorian art.

Djeka remained in Abidjan and painted during the conflict. Like Yubah, he worked continuously out of his studio at home in Bingerville. He does not deny that the conflict influenced his work, but it is not specific to last year’s civil war.

“What theme is more confrontational [than the African heritage] between us?” he asked. “Since my first steps into the arts, conflict is a daily word…especially when we want to [herald the return] of culture in Africa and especially [in Côte d’Ivoire].”

Djeka told me that he has his feet in tradition, but his head in modernism.

One of Stefan Meisel’s clients, Camara Demba, has exhibited at Galerie Lelab and shares a similar artistic process with Djeka in terms of melding the traditional and the modern.

Camara was born into the trade of sculpting and began working in this art form in his childhood. From an early age, he acquired a profound knowledge of materials and older traditions in Ivorian sculpture. Ancestral masks inspired his early works — he carved statues out of wood and embedded shells, metal studs, and nails in the artwork to mimic scarification marks.

In his twenties, Camera put a modern twist on his art. He was able to access Western media and the Internet and became heavily influenced by Manga comics and Western sculptors.

In 2000, he achieved some success and found an agent, who facilitated the sale of his works in Europe; unfortunately, the agent took most of his earnings. The sculptor returned to traditional forms of art to make a living, but a chance meeting with Stefan in 2011 ignited his desire to re-enter the contemporary art world.

Last year, he produced a collection called Demba Manga. In Camara’s 30 creations, ancestral objects and animals like birds, elephants, antelopes, and crocodiles mingle with this world of science fiction and video games. Other sculpted robots have traditional African bodies, but the vibrant colors and heads of Manga superheroes with abnormally large eyes and green or blue hair.

In Stefan’s home, I saw a few of Camara’s sculptures, made of heavy painted wood. The density of the wood and luster of the paints made them look as though they were made of plastic or metal.

One of the sculptures looked like an astronaut; a bicycle pedal jutted out of its head and the left hand was a recycled part from a broken printer or refrigerator. But the sculpture had the emblems of traditional Ivorian culture: the scarification of the body, the mask-like face, the rotund legs.

Stefan described Camara as an artist who was part of the “in-between generation” after Côte d’Ivoire’s independence in 1960.

“He has not yet really detached from his family tradition, but also not yet arrived in an independent, own style. But Camara Demba is a real representation of his time and his generation — a forerunner for African contemporary art, not copying, but influenced in both ways. If he [continues like this], he’ll be the [point of] reference for an upcoming generation.”

An artist, not a beggar

The first time I saw artist Adamo Traoré, he was installed next to the entrance of the shopping mall, Hypermarche Sococé, almost blotted out by dust and smoke. A large umbrella was impaled on the pointed rods of the gate to the shopping mall. Under this, Adamo would sit and paint or run through his inventory.

The 32-year-old artist paints with a pen between his chin and the tip of his remaining arm. He was born with no lower limbs or arms, but is able to walk with a crutch. Before he arrives, a security guard sets up his paintings along the painted bars of the gates; then, when Adamo gets in by taxi from Adjamé, a neighbourhood in Abidjan, the guard helps him organize his papers and canvases as well as his gouache (opaque watercolor) palettes.

I paid Adamo a visit at the end of May. He arrived at Sococé just before noon, wearing a satchel across his body to hold the money he receives.

I crouched under his umbrella to avoid the midday sun. It was hard to believe he had been here since 2007; although Sococé’s owners have been generous in sharing the outdoor space with him, the environment is hardly ideal. Still, he is able to produce fifteen drawings a day — although the painting he must do afterwards takes much longer.

His paintings displayed the landscapes of Côte d’Ivoire: lush, equatorial forests and limpid lakes full of fish (“enough fish for everyone,” he told me). His children’s paintings featured Dora the Explorer in various exotic settings. Religion also figured quite prominently: In one painting, Jesus raised a flame in supplication, his face framed by a wreath of roses; in another, palm fronds and a teal sky framed a mosque.

Although people are appreciative of his art, he admitted it can take months to make a sale and the sun and rain degrade his paintings. He has hopes of getting a workspace indoors; even after five years at Sococé, his optimism seemed undiminished.

When Adamo was nine years old, he met the director of Providence, a center for physically disabled children; its primary goal was to make the 200 children at the center independent. French-born Marie Odile Bilberon welcomed Adamo to the center and taught him how to walk, speak French, and brush his teeth. She also introduced him to drawing and taught him how to set and harmonize colors. He participated in exhibitions and produced greeting cards that were sold by Providence to raise funds for the institution.

One day, his mother came to Marie Odile to ask her for money and Marie Odile refused. Adamo could not believe that they could not spare a few francs for his mother after everything he had given to the organization. In 2000, he left and moved in with friends in the district of Abobo, where he begged in the streets to survive.

But in 2005, he made the decision to return to painting and eventually took up residence at Sococé. He has had few absences except during last year’s crisis, when he was forced to take refuge in his home in Abobo.

I told Adamo that this was my first West African art purchase and asked him to pick which painting he wanted me to have. First, he showed me a muted painting in browns and beiges. At first glance, it looked like an amorphous object that had been buried in the ground. Adamo told me it was a picture of a womb and the baby was physically disabled. Above the baby were the words “Abortion is not right.”

“You should not destroy what God gave you,” he said before moving on to the next painting; in that one, Jesus was holding a candle.

“He gives me courage,” he said. “I am an artist. I am not a beggar.” He repeated that sentence several times that day.

“I’ll take this one,” I said. As I reached forward to put the money in his satchel, a woman tossed 5,000 CFA ($10 USD) out her car window. Adamo smiled just long enough to catch her eye, then returned to his sheaf of papers and struck his latest sale off the list.

[Note: This story was produced by the Glimpse Correspondents Program, in which writers and photographers develop long-form narratives for Matador.]