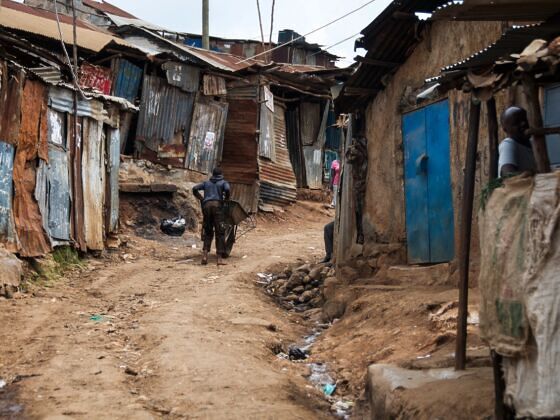

HUNDREDS OF MILES AWAY FROM THE SLUM OF KIBERA, in a small village in Western Kenya, as everyone else in the village closes their doors for the evening, a group of fishermen are preparing for their evening’s work.

With minimal electricity for miles, the night air is black as soot. As they walk, their arms swing below them, dropping off into the night, their hands obscured even to themselves by the darkness.