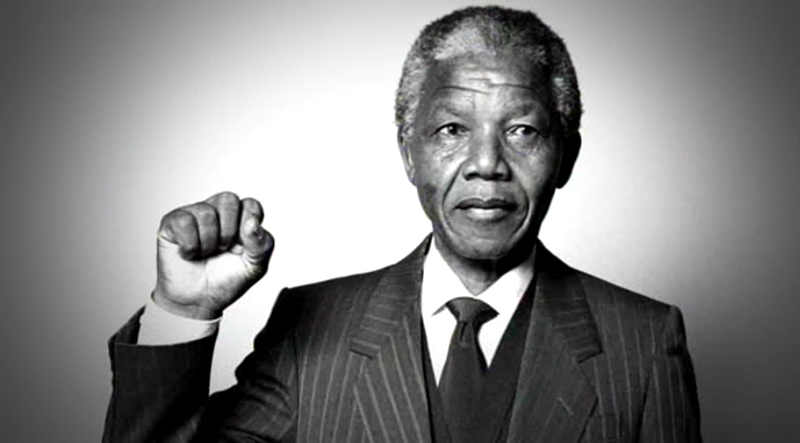

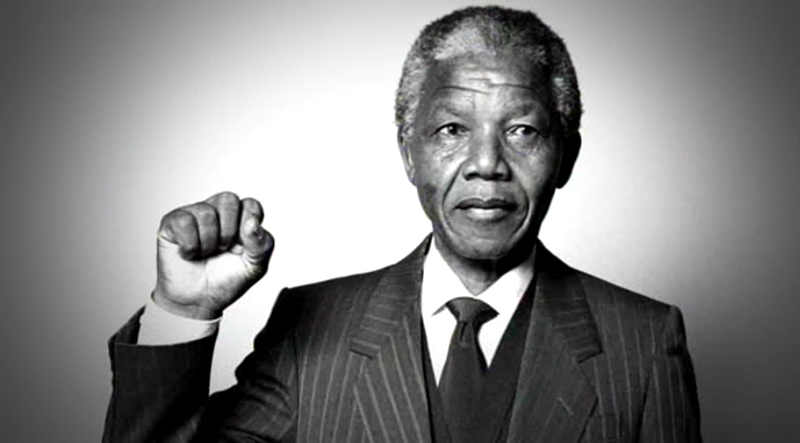

LIVING AWAY from the place you call home, where your family is, where your culture lives, can be most difficult when you miss significant events. Birthdays, weddings, births, and deaths are most difficult. Today, South Africans around the world are feeling the pang of being away from home on one of the most important days in South African — and indeed world — history.

Hearing the news as I woke this morning, I began to weep at the tragedy of his passing. A tragedy that lies not in the death of a great man, as most South Africans have wished a peaceful end to his very long life. Rather, it lies in the death of the great hope that his presence inspired. Who can we look to now, to lead us through the many difficulties ahead in the development of our young democracy? Who can we trust to embody the ethics written in our constitution? Today we mourn not the man, but the lack of the ideals and philosophies he came to symbolise.

The greater tragedy is that the potential to mirror his actions and the commitment to his beliefs are within us all. While his actions were revolutionary, his ideas were not. They were simple tenets, reminders of that which a child already knows. We are all born humanitarians, taught only by our cultures and politics to fear and despise each other, to see invented differences between us. In truth, though, we share much more than we admit.

Mandela’s greatness is rooted in a basic principle: integrity despite great adversity. Learning about his life, we see no discrepancy between appearance and reality. He had an unfailing commitment to his beliefs, without exception and despite the consequent sacrifices. To live as Madiba did, we need only do this: acknowledge our common humanity and act on our beliefs.

For South Africans, the potential lives in us and yet we often turn from it, afraid. What stops many of us is fear and resentment. More than many of the acts of oppression and discrimination during apartheid, a high rate of violent crime has deformed the nation in ways that even Mandela’s attempts to bind us together cannot combat. Our fear of crime leads to fear of unfamiliar spaces, of unfamiliar faces, and a distrust for the unknown. We do not talk to strangers.

But today, there will be a connection between all South Africans that no one will ignore. There will be a grief shared by all races and classes that will manifest on the streets in unpredictable ways. Strangers might greet each other without fear; they may even share a moment of acknowledgment — a nod, handshake, conversation. And while there is potential for great resentment, or an abandonment of all hope, there may also be a new bridge to communication and community.

Walking down the street in a country across the globe, I search the faces of those catching the bus or eating in a restaurant for acknowledgment of this great moment. Met with only indifference or obliviousness, I turn to online media for messages of tribute and devotion. I fly a flag at half-mast from my balcony, and suspect that its presence confounds most residents in this block. I want to educate my students about this great leader, to talk to people about how his life’s work was a manifestation of his humanitarian philosophies. But I have not the foreign tongue to express my sorrow. I refuse to reduce Madiba’s story to the animated, comical string of nouns and verbs I use to communicate in this place that feels even more alien today.

So I will quietly remember his life, pen these words, and long for home.

This post was originally on The Culture Muncher and is reprinted here with permission.