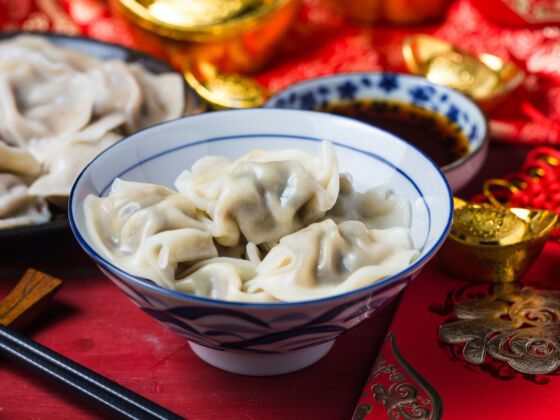

For most Chinese families, jiaozi, or Chinese dumplings, are as essential to the Chinese New Year as roast turkeys are to Americans on Thanksgiving. In the modern era, most Chinese families prepare platters of jiaozi as part of their celebrations, but the tradition can likely be traced back to the imperial court of the Ming Dynasty.

“People get up early on new year’s day […] drink herbal liqueur, and eat dumplings,” wrote a once-powerful eunuch in his memoir. “A coin was sometimes hidden in a dumpling as a lucky token.”