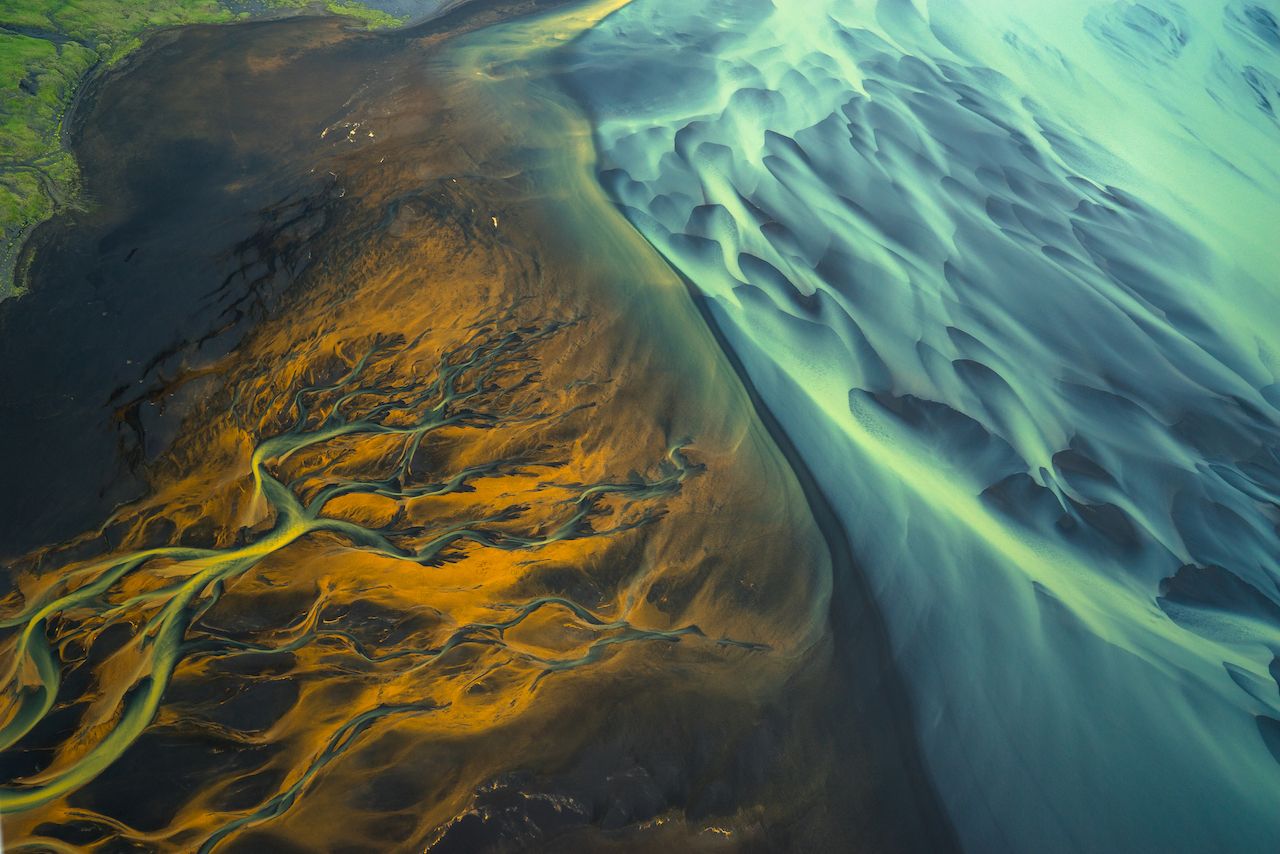

Iceland’s glacial rivers flow from the edges of the country’s Highlands, often spanning 100 miles or more before spilling into the frigid waters of the North Atlantic. At Glacier’s End is an anthem to these glacial rivers and those working to protect them, a stunning book uniting the work of renowned surf and adventure photographer Chris Burkard and writer Matt McDonald.

The coffee-table-perfect collection showcases Burkard’s photographs of the Icelandic Highlands over the span of more than seven years. McDonald’s words tell the stories behind the photos and give us background on the urgent need to protect these rivers and the glaciers that spawned them through the creation of a conservation area under the name Highlands National Park.

Matador spoke with Burkard and McDonald and learned that the goal of the book, like the goal of the park itself, is to both protect the sacredness of the Icelandic Highlands and simultaneously provide an economic driver to the country’s small coastal towns. And for all of us, a new reason to visit Iceland.