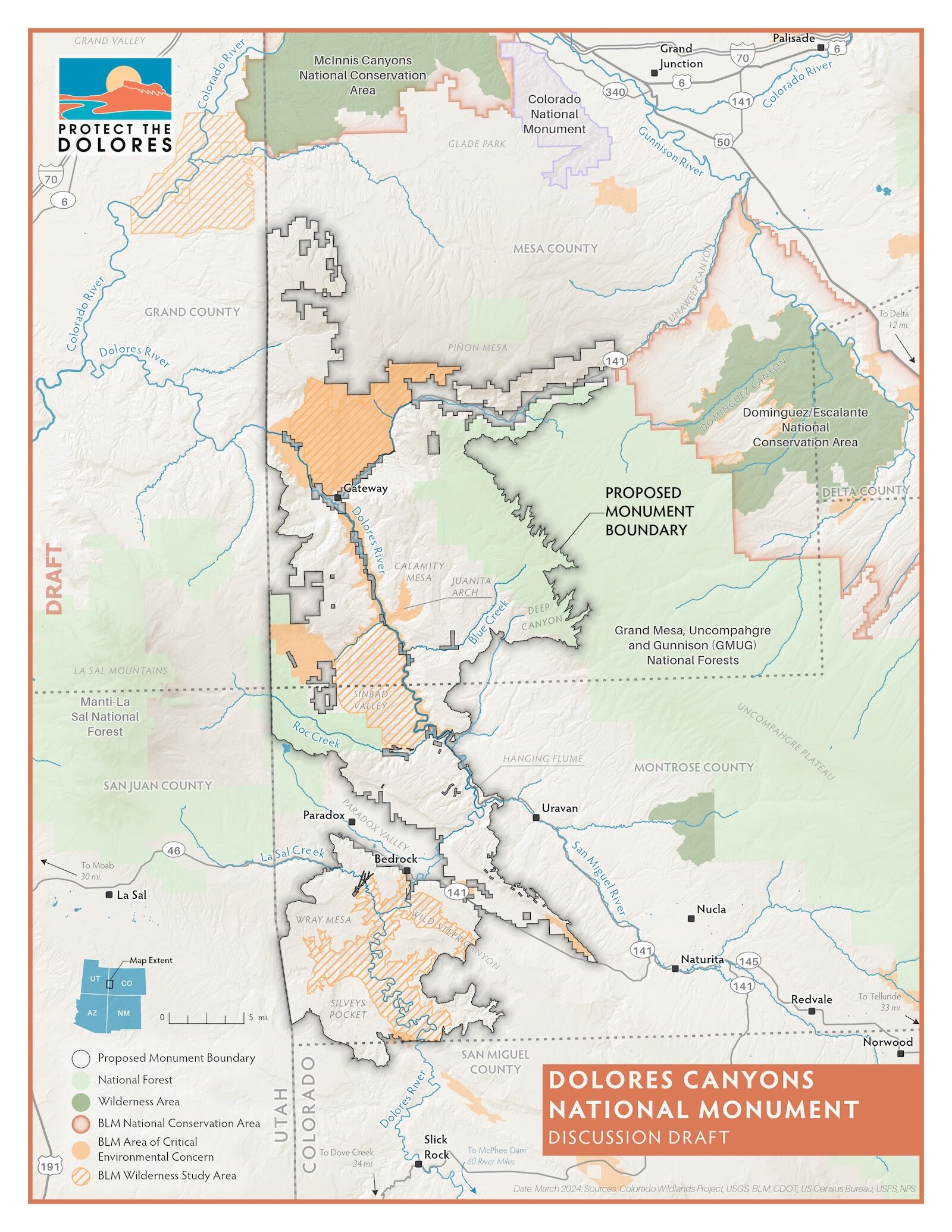

I first saw a “Protect The Dolores” sign in a neighbor’s yard in 2023. Before that, I’d heard rumor that a movement to establish the Dolores Canyons National Monument around the Dolores River in Colorado’s Mesa and Montrose counties was taking hold. I’m typically an adamant supporter of conservation efforts like this, but opponents to the national monument plan included many people I know who live near or in Colorado’s Grand Valley, which is the largest population center near the proposed monument. I hesitated to voice support because some of these concerns spoke to me as a local resident: Do we want more people coming through? Will federal management result in tighter restrictions on access to outdoor recreation?

I’ve since come around to support the designation efforts. The movement to protect the area has laid bare how it will or won’t impact the things that matter to the outdoor community. Intense scrutiny and controversy, in fact, is ultimately why it will be successful.