The Mercedes belonging to John Lee Spencer didn’t seem to concern itself with actual “roads.” It bounced over the uneven lawn between Highway 17 and the LeJeune Memorial Gardens in Jacksonville, North Carolina, like an angry humvee, running the opposite direction of oncoming traffic. When it finally jerked to a stop on the grass in front of the Montford Point Marine Memorial, the window slid down, and a patch of silver hair popped out.

The Story of the First Black Marines Lives on in This North Carolina Town

“I went down there to the end, but the gate was closed,” the 92-year-old World War II veteran said. “So I had to go back.”

His version of “going back” would get most people, at best, a hefty traffic violation. At worst, most people would be investigated by the Department of Homeland Security. But when the memorial you’re illegally off-roading toward was erected in your honor, people tend to let things slide.

John Lee Spencer isn’t just a World War II veteran. He is also one of the few remaining Montford Point Marines, which was the group that broke the Marine Corps color barrier in the early 1940s. And though their story is a great one, it is somehow an often overlooked part of American history.

The Marine Corps was a whites-only institution for more than 150 years.

I served in the Marine Corps in the early 2000s, and I’d always thought of it as a place that felt truly color blind. It wasn’t a kumbaya, buy-the-world-a-Coke harmony by any stretch, but more like the scene in Full Metal Jacket where the sadistic drill instructor rattles off a long list of racial slurs and finishes by saying, “There is no racial bigotry here … You are all equally worthless.”

But this was not always the case.

The Marine Corps has been around since 1775, but it didn’t admit any Black recruits until 1941. That year, President Franklin Roosevelt signed an executive order outlawing racial discrimination in the military. Then-Commandant Thomas Holcomb (the highest-ranking Marine Corps officer) made his feelings on the matter known at the time, saying publicly, “If it were a question of having a Marine Corps of 5,000 whites or 250,000 negroes, I’d rather have the whites.”

This was the Marine Corps that the Montford Point Marines elected to join.

Photo: Visit Jacksonville NC

Undeterred, they began their training in a fully segregated boot camp at Montford Point near Jacksonville, North Carolina. White recruits still trained at Parris Island, South Carolina, and San Diego, California, but Spencer insists training at Montford Point was tougher.

“It was hell on Earth,” Spencer says while seated in front of the memorial, which stands outside of the former site of the Black boot camp. “It degraded you completely.”

The first set of recruits had to build many of Montford Point’s facilities in addition to completing their regular basic training. Because there were no Black Marines, all of the drill instructors were white, and many weren’t especially thrilled at the prospect of allowing Black people into the Corps. Black Marines were never allowed on base without a white Marine escort. And because Black recruits weren’t permitted to ride through town, they had to get on boats at 4 AM and travel to the rifle range over water rather than the more direct route by land.

“We had it hard,” Spencer remembers. “We had harder training than any of them. We had to prove that we could stand up to all the white Marines. But we survived because we was used to the segregation. All those demons from down South, it wasn’t nothing new to us.”

Spencer is from North Carolina’s outer banks and maintains that had he and his fellow recruits been sent to train with their white counterparts, they never would have survived.

“The Marine Corps was one of the most prejudiced, bigoted outfits in the world,” he says. “And training at Parris Island, you were in the middle of the Klu Klux Klan. There would have been a war or revolution — we’d have never survived. They had to put us somewhere you could prove yourself, by yourself.”

The first Black Marines had to fight harder, prove more

Photo: Montford Point Memorial Project/Facebook

Spencer, and over 20,000 other Black recruits, proved themselves up to the task. Still, the Marine Corps initially wouldn’t let Black Marines fight on the front lines.

“Primarily, they were ammo carriers,” Houston Shinal, a member of the National Montford Point Marines Association, tells me as he tours me around the memorial. “They’d bring ammo to the white Marines on the front line. But at some point, the [Gunnery Sergeant] is gonna say, ‘Pick up a rifle and fill that hole,’ which is how they ended up fighting in World War II.”

He points to a map on the Montford Point Memorial to all of the places the Marines who trained here fought. Most locations were in the Pacific, including Guadalcanal where Spencer had been. Also at the memorial stands a bronze statue of a Black Marine charging up a hill, rifle in hand. An ammo can sits at the base of his feet.

“It was always an uphill struggle for them to stay in the Marine Corps,” Shinal says.

After the war, the struggle didn’t end. Spencer, like many Black service members, faced the harsh realities of racism and segregation after returning home — including in the Marine Corps, which didn’t integrate its units until 1948.

“It dawned on us that it hadn’t changed all that much,” Spencer says. “But a lot of us died for the freedom of the United States, so we felt we should have just as much rights as anybody. Enemies that you’d been fighting against — German prisoners, the Japanese — they could ride in the front. We had to ride in the back. So it made you kind of wonder, why’d you do it?”

A search for the lost Marines and a fitting memorial

Photo: Visit Jacksonville NC

That bitter taste of resentment, along with a Navy yard fire that destroyed many of Montford Point’s records, is a big reason why the story of these groundbreaking Marines gets glossed over. Many Montford Point veterans just don’t want to talk about it.

“A lot of the Montford Pointers did not have a great time,” Shinal says. “To their families, they’d say ‘Marine Corps,’ and they’d wave their hand off, and that would be the extent of the conversation.”

With the help of the City of Jacksonville, the Montford Point Marine Association — a sort of Alumni club of Montford Pointers that’s now open to anyone who’s served — set out to find them.

“Many of these guys, they came back and didn’t tell anyone they were in the service,” says Jacksonville’s assistant city manager Glenn Hargett. “There are a lot of African American family reunions that occur in July. We put out a campaign that said, ‘If you’re gathering with family, ask your grandfather if he served in the Marines.’ And we got a surge in reports that went and called the Montford Point Marine Association after that.”

To date, they’ve identified about 20,000 people, but Shinal admits the record is incomplete.

In 2008, the association began to design and fundraise for a memorial to honor the men who broke the Marine Corps color barrier. They commissioned architect Liam Wright, whose uncle had been a Montford Pointer, to design the memorial. Recognition was starting to come in elsewhere, too. The Montford Point Marines were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2011. In 2016, the Montford Point Marines Memorial was dedicated. It’s the only memorial in the gardens fully visible from the highway.

Photo: Visit Jacksonville NC

The memorial consists of three concentric circles, which represent the Montford Point Marines, the Marine Corps, and society. The first is a restored, 90-mm M1A1 anti-aircraft gun, which the association found online from a collector in Tennessee. It represents the gun that combat units from Montford Point used in World War II.

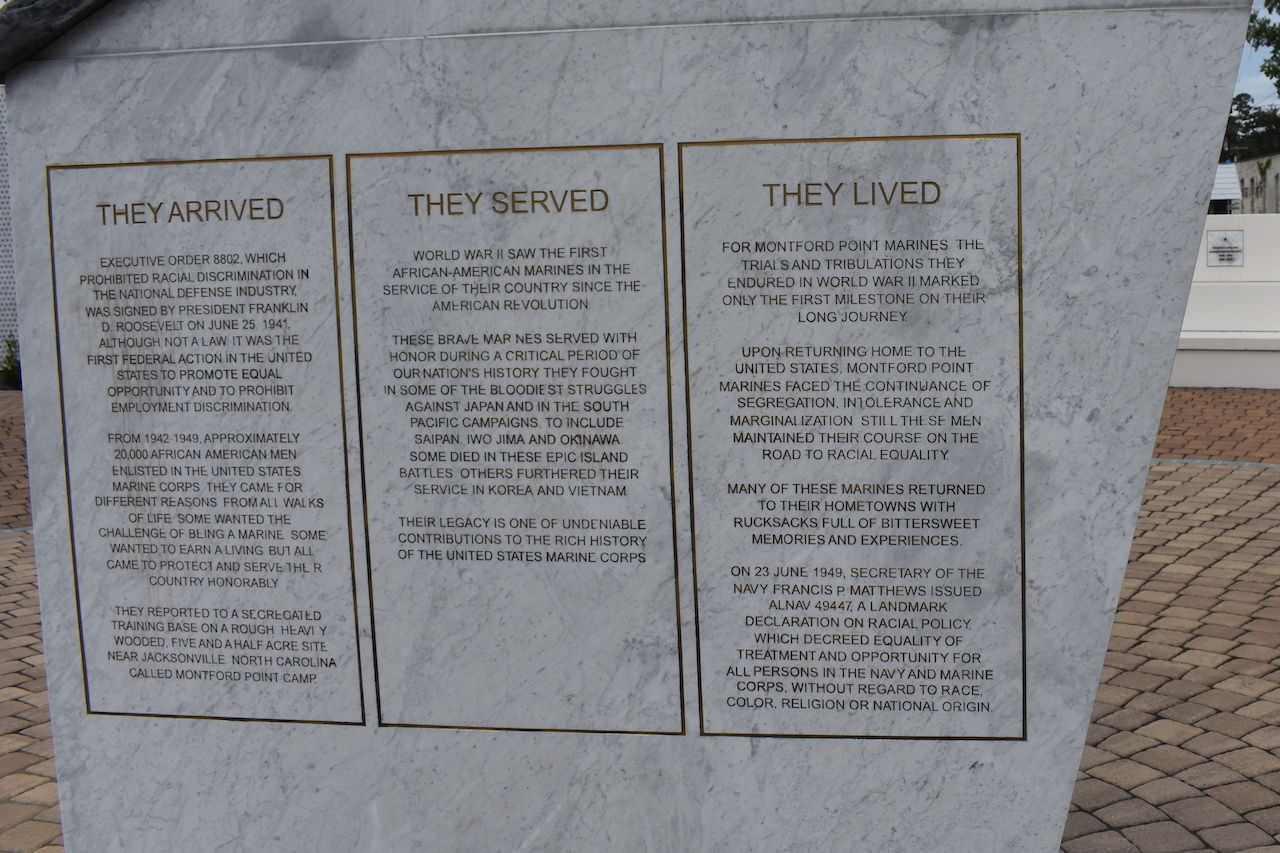

The second circle is the statue of the Marine advancing uphill with an ammo can at his feet. It’s representative of Black Marines’ transition from support staff to combat fighters. It’s also inscribed with a map of all the places the Montford Point Marines fought, and the words, “They Arrived. They Served. They Lived.”

Photo: Visit Jacksonville NC

The third circle contains a bench and several trees intended for reflection and meditation. It represents the continued struggle of war and segregation that Marines found when they returned home.

All the circles intersect in the middle of the Memorial, which, Shinal tells me, is the overlying message of the project.

“The only place that any change took place was where all the circles crossed,” he says. “Those folks where the circles cross had enough communication and worked hard enough at it that change happened.”

A wall of 20,000 stars sits outside the circles, which represent the 20,000 or so men who trained here between 1942 and 1948. If you look closely at the bottom of the wall, you’ll see a few rows of stars rotated in a different angle than the rest. They are almost impossible to notice.

“That symbolizes that once you put Marines all in formation, you can’t tell one from the other,” Shinal says. “The differences become insignificant once you look at the whole.”

Every August 26, it hosts an anniversary celebration where as many surviving Montford Pointers as possible return. According to Hargett, there’s not a dry eye in the house.

A legacy that continues today

Photo: Visit Jacksonville NC

Montford Point was renamed Camp Johnson in 1974, after Sgt. Major Gilbert “Hashmark” Johnson, who was the first African American Marine to earn that rank. Since then, generations of Marines, like myself, have trained at the Combat Service Support Schools now located on the camp. Few, if any, know its role in American history. Aside from instances like a platoon sergeant casually saying, “This used to be the Black boot camp,” when we passed the entrance to the Montford Point Museum, it was never mentioned.

Today, the memorial is open to the public, and it’s one of the more striking features of this coastal Carolina base town. While it would be easy to zip through on a road trip to the Outer Banks or down to Wrightsville Beach, it’s worth a stop to understand how close we are to an era the Marine Corps would like to forget. And how, thanks to men like John Lee Spencer and his devil-may-care Mercedes, no one will ever again forget the Marines of Montford Point.