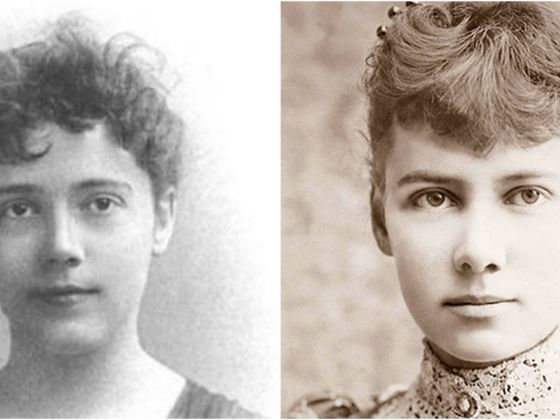

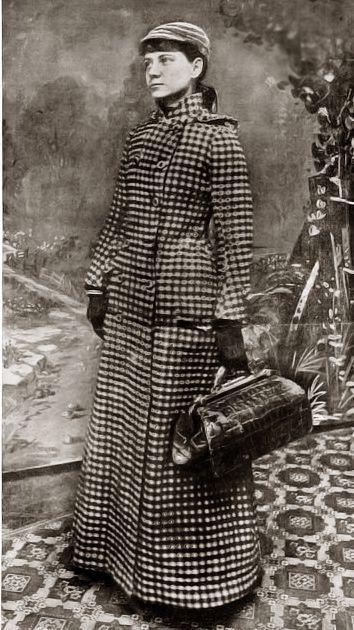

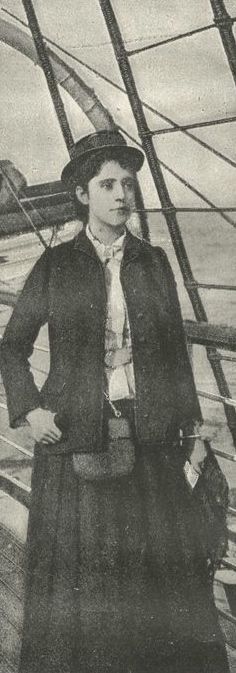

Today’s solo female travel movement — the subject of so many articles, books, and blogs, the inspiration for so many trips and lifestyles — can trace its roots in America back to two people: Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland.

Bly and Bisland were New York-based reporters in the late 1880s, at a time when American women had still not been granted the right to vote. Women in the field of journalism in this era had a particularly difficult time — most publications would not hire them unless it was to write about “women’s issues,” like housekeeping and fashion. They were paid substantially less than men and were rarely given good assignments. They were certainly not sent out on location or into potentially fraught reporting situations, as editors rationalized that it would be irresponsible to put women in harm’s way.

Out of this muck rose Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland. Both, in the span of a few short months, would become nationally famous as travelers — or, to be more specific, as “globe-girdlers”: circumnavigators of the planet.