Before every match, the men of New Zealand’s national rugby team, the All Blacks, have a ritual: They assemble on the pitch facing their opponents; assume a low, squat-like stance; and perform a haka, or traditional Māori dance.

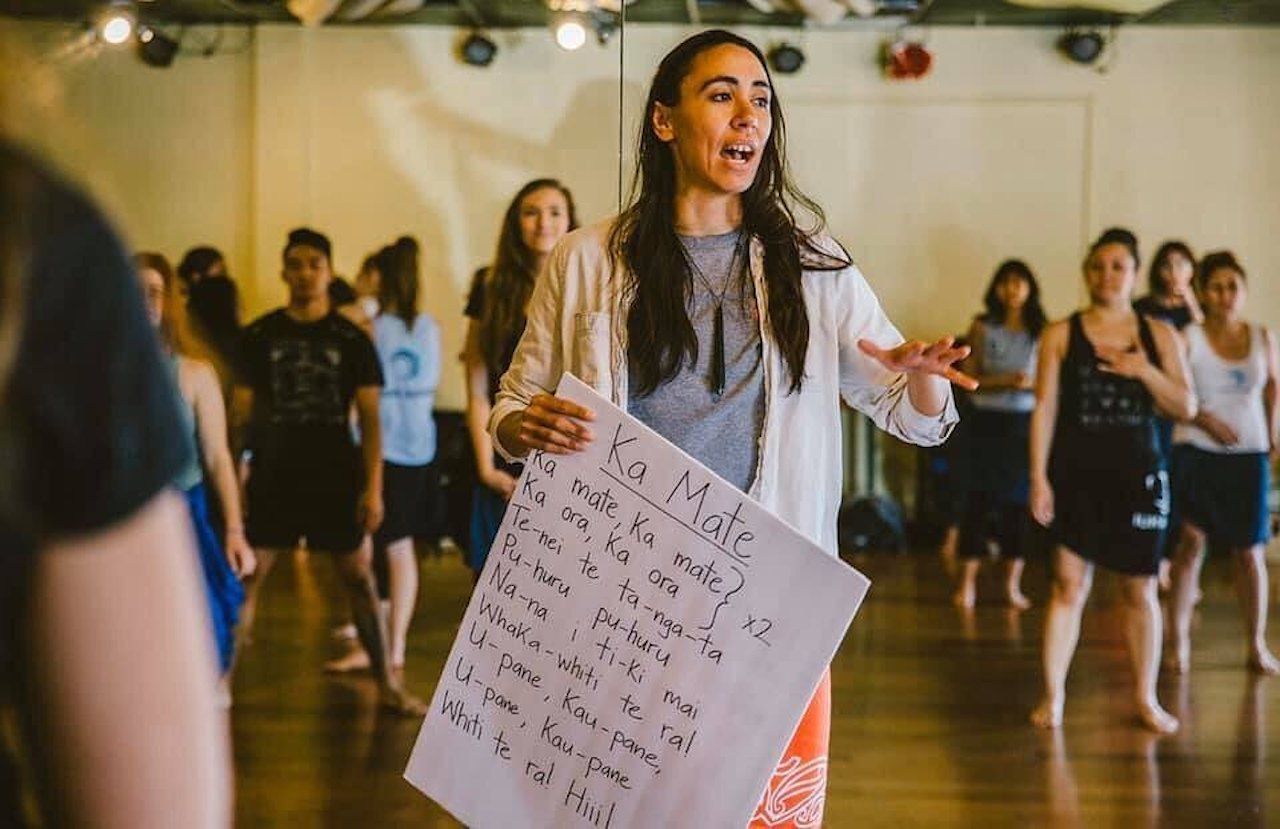

It’s a scene spectators around the world have witnessed, rugby fans or not. Recordings of the All Blacks performing the “Ka Mate” or “Kapa o Pango” haka have racked up millions of views on YouTube and social media. Videos of schoolboys, wedding guests, and even actor Jason Momoa performing a haka with members of Auckland’s Ultimate Fighting Championship team at the premiere of his Aquaman film have also gone viral. Yet despite the growing global awareness of the Māori custom, those less familiar with New Zealand’s indigenous culture or national sport may be surprised to learn that the Black Ferns, the women’s rugby union team, also perform a pre-game haka, or that Māori women traditionally participated in the practice at all.