Imagine traveling to Egypt, walking into a temple or pyramid, and actually being able to translate the ancient hieroglyphics on the wall — that would be a crazy cool skill that would deeply enrich your trip and blow your traveling companions away. The early form of writing is complex, but it’s actually within reach to learn the rudiments of the “Language of the Gods” with a little planning and studying. Here’s how you can master at least the basics before your excursion to the land of the pharaohs.

How to Interpret Hieroglyphics on Your Next Egypt Trip

-

- What are hieroglyphics?

- Where to see hieroglyphics in Egypt

- Learning hieroglyphics

- Common hieroglyphs and how to recognize them

What are hieroglyphics?

Hieroglyphics is an ancient Egyptian system of writing composed of individual shapes called hieroglyphs. Hieros translates to “sacred” in Greek, and glyphos means “signs.” The writing is ancestral to Latin, Cyrillic, Arabic, and Brahmin scripts.

There are more than 1,000 letters, syllables, numbers, and representative hieroglyphs in the set of characters. The system was invented in about 3000 BC; however, new finds are pushing that date back up to 2,000 years earlier. They were used for about 3,600 years (or 5,600 years if those new finds are proven true).

Scribes carved hieroglyphics pretty much all over Ancient Egypt. They etched them in stone on the walls of tombs and public monuments. They wrote them on papyrus and used them to decorate artifacts. They recorded everyday life, told complicated stories, labeled goods, and honored pharaohs’ regal deeds. The Egyptians used a cursive, squiggler form of hieroglyphics for religious texts, mostly inscribing them on wood and papyrus. They included specific dates, entailing the day, month, year, and season.

Photo: Viiviien/Shutterstock

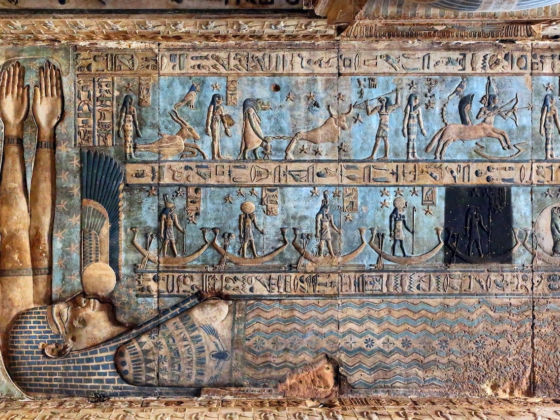

It was the French who, in 1799, discovered the artifact that would serve as a decoder for hieroglyphs, and it was Frenchman Jean-François Champollion who deciphered hieroglyphics in 1822. To do so, he used the Rosetta Stone, a slab of rock carved in 196 BC that’s currently displayed at the British Museum in London. The Rosetta Stone had the same message written in the two languages the Egyptians used at the time (Egyptian and Greek) and in three scripts (hieroglyphs; demotic, the native Egyptian script used for daily purposes; and Greek). Upon translating the stone and mastering hieroglyphics, endless details about the ancient Egyptians’ lives were revealed.

Where to see hieroglyphics in Egypt

While well-preserved hieroglyphics are to be found both in museums and pretty much everywhere you go in Egypt, here are three places that feature more than others.

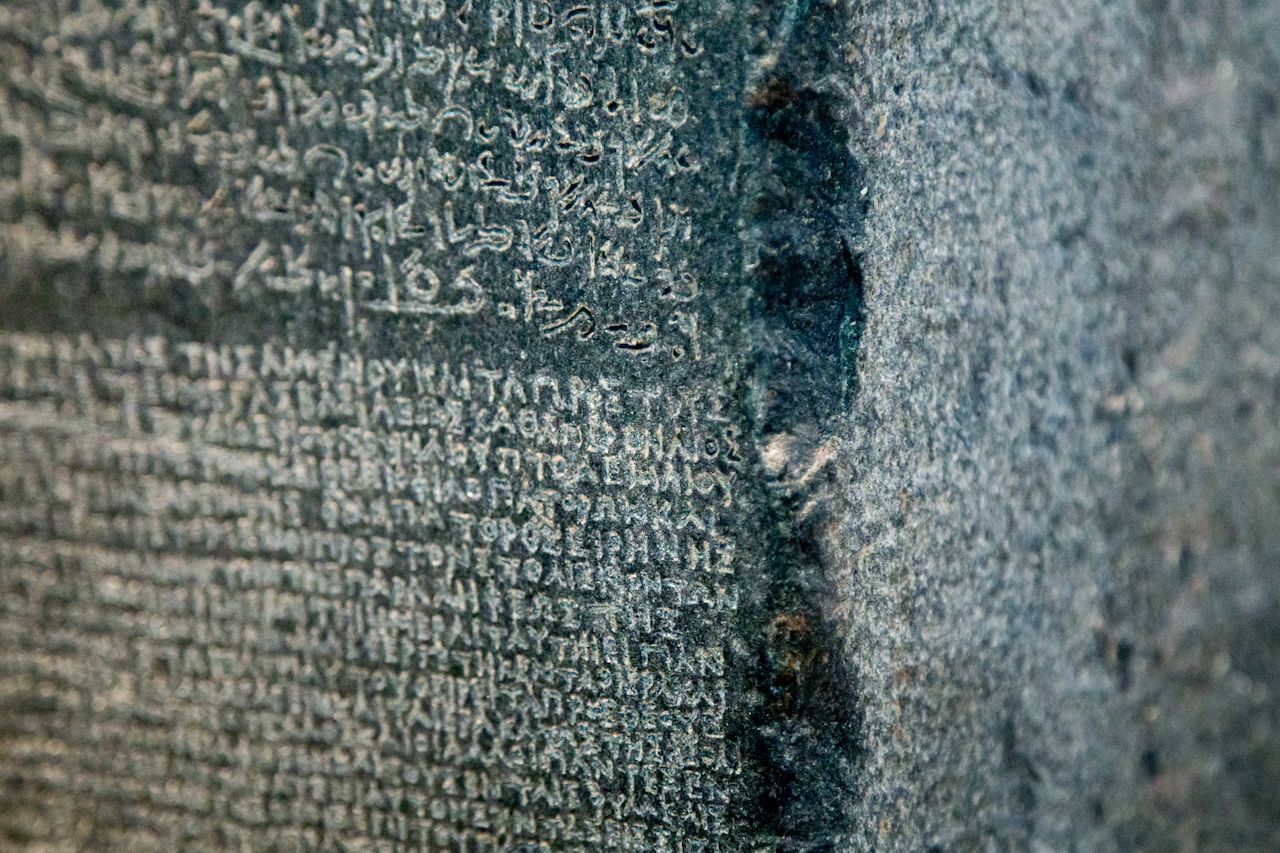

Abu Simbel temples

Photo: Anton_Ivanov/Shutterstock

The Abu Simbel temples are located on the western bank of Lake Nasser near the border with Sudan. They were carved out of a mountain in the 13th century BC to honor Queen Nefertari. Archaeologists relocated the entire temple complex in 1968 to a site high atop the Aswan Dam in order to protect them from the Nile’s imminent flooding. Hieroglyphics occur throughout the temples.

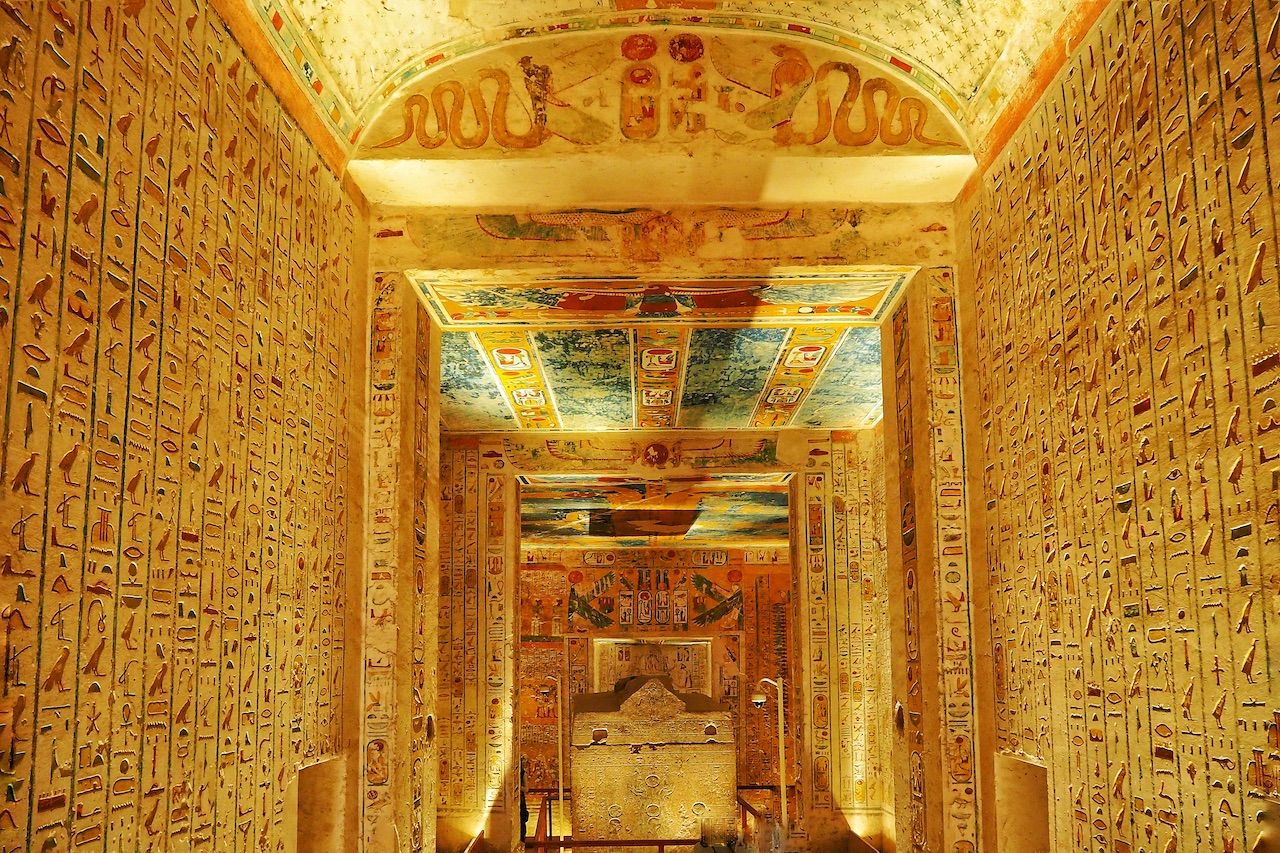

Valley of the Kings

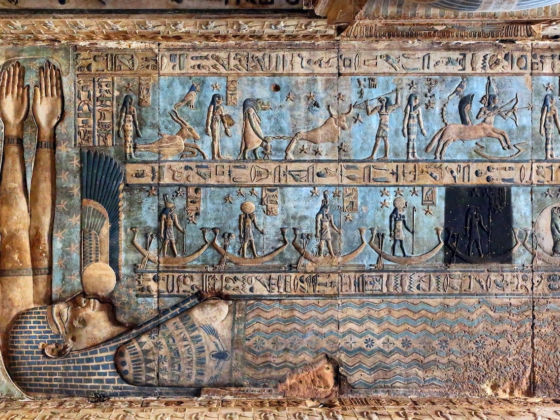

Photo: kritsadap/Shutterstock

Hieroglyphics in the tombs of the Valley of the Kings helped Egyptologists unravel the chronology of the pharaohs’ rulership. Most of the tombs are elaborately decorated with each pharaoh’s accomplishments and day-to-day doings.

Saqqara

Photo: NiarKrad/Shutterstock

Saqqara is a vast, 4,400-year-old necropolis about 20 miles south of Cairo. While many, if not most, tombs feature hieroglyphs, one in particular is absolutely covered with them. It belongs to Wahtye, a royal priest who served King Neferirkare.

Learning hieroglyphics

Photo: akimov konstantin/Shutterstock

To learn the elements of the script before you go to Egypt, you could take courses in Egyptology at a university or, better yet, take free (or donation-based) online lessons from a site like Egyptianhieroglyphs.net. Alternatively, you could check out a book from your local library. There is no shortage of introductory texts, such as Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs: A Practical Guide.

The basics

Aesthetics are prioritized over writing direction — hieroglyphics were supposed to be beautiful — which can make things challengings for beginners. Hieroglyphs can be read left to right or vice versa and are arranged in both rows and columns. To begin, it’s vital to determine which direction to read the writing. You can tell which direction to read by finding a human figure or animal and seeing which way its head is turned. Figures face the beginning of the line of “text.” Thankfully, the upper glyphs are always read before the lower ones, so you don’t have to figure out whether to read from the bottom up or the top down.

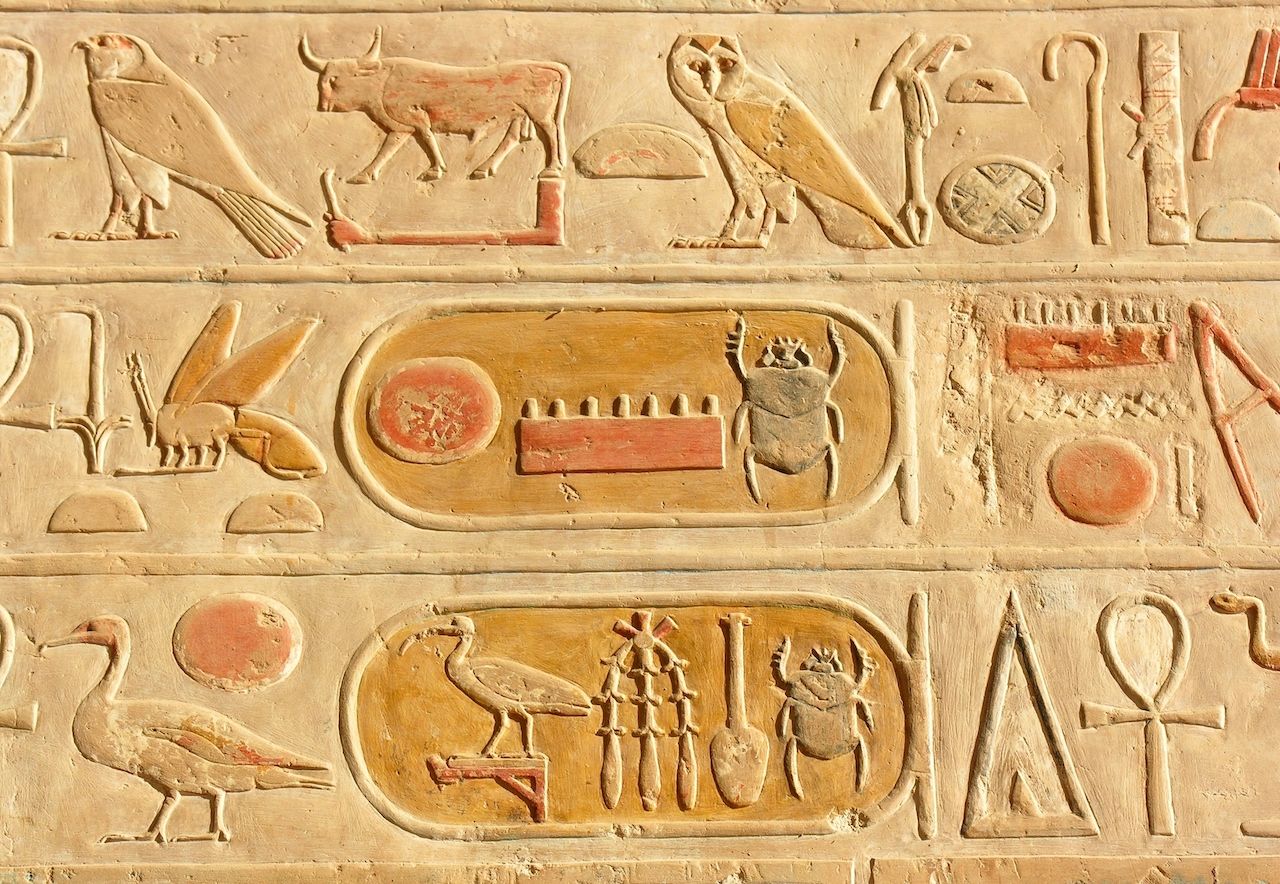

The names of royals are encircled in an oval with a horizontal line at the end called a cartouche. Keep your eyes peeled for those — they are easy to spot.

Photo: Bildagentur Zoonar GmbH/Shutterstock

Some glyphs can be turned into letters or converted into sounds. There are fewer of these “letters” than in the Latin alphabet, but it’s a start for writing your name in hieroglyphs, for example. The following video from the Royal Ontario Museum teaches that skill.

First, you have to sound your name out phonetically. You’ll also need a hieroglyph key, and you’ll find that the letters and the sounds don’t match up intuitively. You can write your name either left to right or right to left and vertically or horizontally.

Numbers are on a base-10 system using everything from simple strokes (for one) to frogs (for 100,000). Three frogs would be 300,000. That’s also how the ancient Egyptians pluralized nouns. Three bird symbols meant there were three birds.

Grammar is more advanced. Hieroglyphics are crafted in blocks. Each block represents a word, phrase, or idea. Some glyphs represent entire concepts unto themselves. These are logograms (the glyph for “sun” looks somewhat like the sun) and determinatives, glyphs that tell the reader what the logogram is doing or its qualities (for example, the sun is setting).

Common hieroglyphs and how to recognize them

Photo: Stephen Chung/Shutterstock

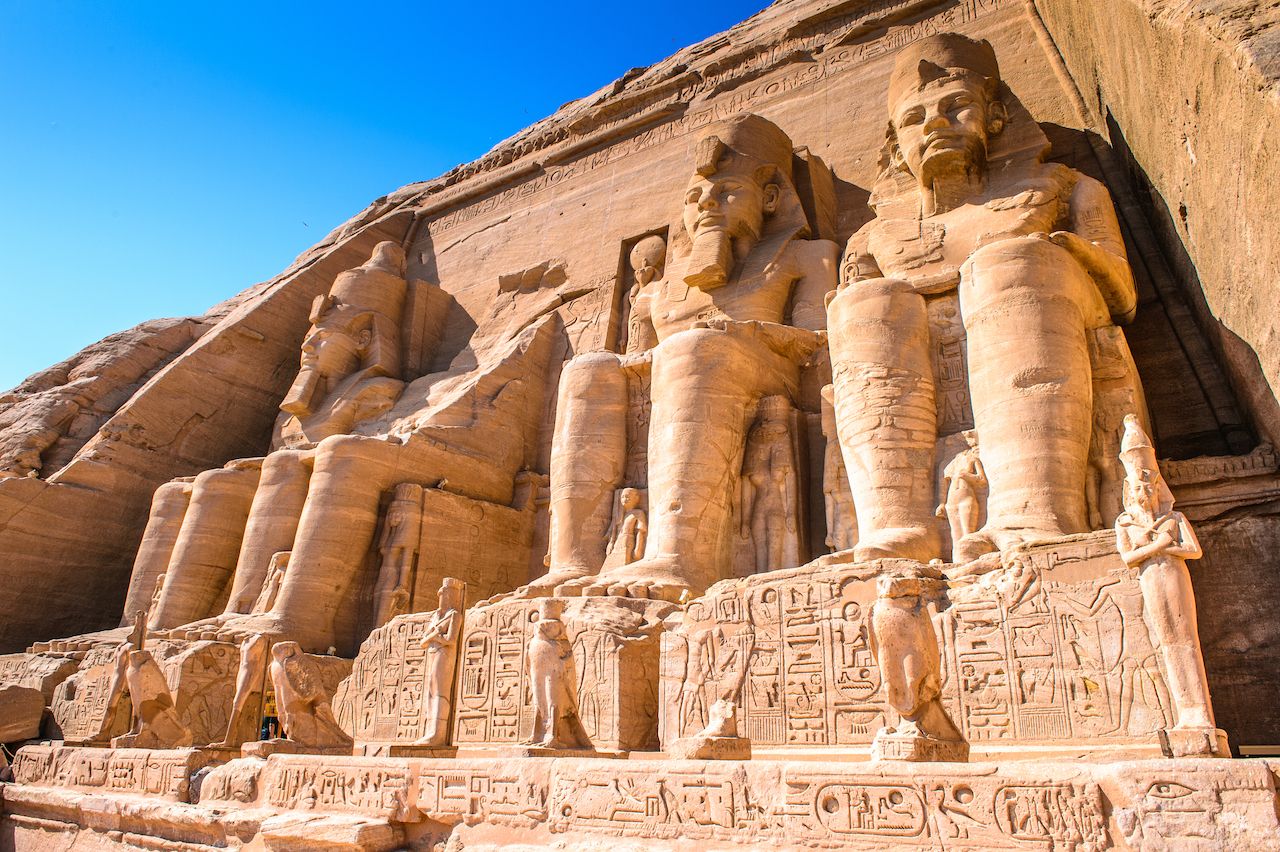

The most common hieroglyphs reflect the ancient Egyptians’ deeply held values, like their individual gods, such as Horus, the sky god, depicted as a falcon or a man with a falcon head, or Athor, the goddess of fertility and motherhood, represented with cow horns between which she holds the Sun.

Photo: FlavoredPixels/Shutterstock

Others, like the sun and water glyphs, were, and remain, vital parts of the extreme desert environment. These tend to be glyphs that look at least somewhat like what they represent. The sun is a circle with rays coming off it. The symbol for water is a zigzag, denoting waves on the Nile, or on the bordering Mediterranean and Red Seas.

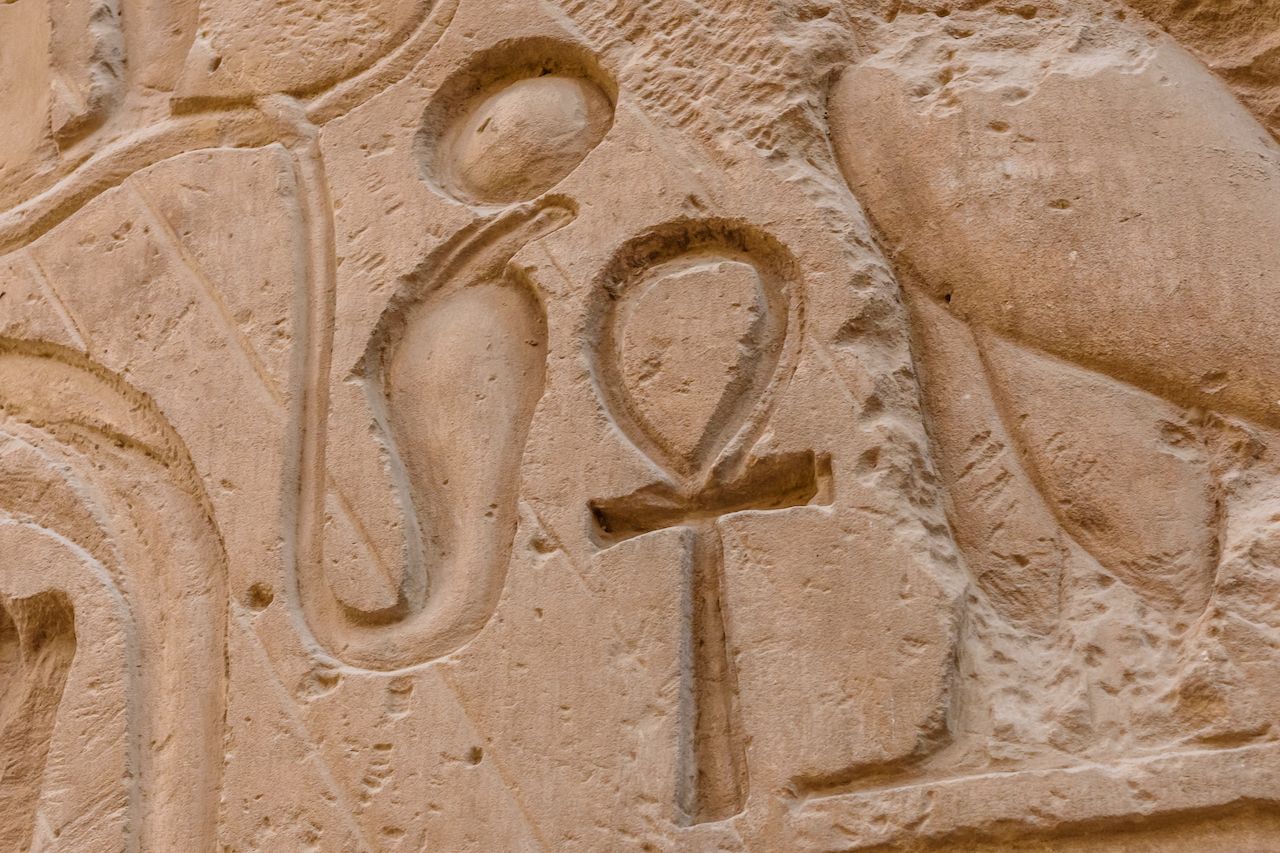

Photo: Ihor Bondarenko/Shutterstock

Some glyphs remain part of the international zeitgeist today, for example, the ankh, the hieroglyph for life, which is actually representative of a biological yin yang. The loop at the top represents the female womb, and the bottom part represents the phallus.