Snow-capped mountains, sweeping vistas, and rangers in broad-brimmed flat hats — these are the typical images conjured by the United States National Park Service. Rainbows may occasionally make the cut, but not the LGBTQ kind. Queer folx aren’t poster children for the federal agency presiding over the country’s parks, monuments, and other historical properties.

7 LGBTQ Heritage Sites in the National Park Service to Visit

Shocking? Not exactly. Although the National Park Service (NPS) was created in 1916 to protect sites of both ecological and historical significance, it took nearly one hundred years before any LGBTQ-associated sites were deemed worthy of preservation. Today, there are over 90,000 locations listed as National Historic Landmarks and featured on the National Register of Historic Places. Less than forty NPS-featured destinations currently connect to LGBTQ heritage.

But excluding queer people and places from the NPS is like watching Drag Race and skipping Untucked — you’re only getting half the story.

There is no Union victory in the Civil War without the trans soldier who fought forty of its battles. June’s Pride parades would not take place without the Stonewall Uprising. Proud LGBTQ politicians like Pete Buttigieg and Sarah McBride might not openly serve the country if the Cherry Grove Community House wasn’t constructed decades prior. LGBTQ Americans are an integral part of US culture. Their stories are the seedlings of life as we know it today.

Luckily, the NPS is beginning to cultivate those seedlings. Thanks to a 2014 initiative to increase queer visibility in the US, there have been new LGBTQ sites added to the NPS almost every year. By including these perspectives on US history, the NPS is finally recognizing what LGBTQ folx have always known: we’ve always been here, we’ve always been queer, and our historical significance has always been national-park worthy.

Here are seven influential LGBTQ sites listed by the NPS that reframe American life with a Gilbert Baker-style rainbow.

1. Stonewall National Monument — New York, New York

Photo: PeskyMonkey/Shutterstock

There’s much uncertainty surrounding the mythic uprising that erupted after police raided the Stonewall Inn in the early hours of June 28th, 1969. Why did officers show up on this particular date? Why, on this night, did the patrons respond with resistance? Who threw the first brick? When did activists Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera arrive? Still, one statement about this night remains unimpeachable: the Stonewall Uprising was a turning point for the modern LGBTQ rights movement.

According to gay rights activist Frank Kameny, “By the time of Stonewall…we had fifty to sixty gay groups in the country. A year later, there were at least fifteen hundred. By two years later, to the extent that counts could be made, it was twenty-five hundred.”

Had it not been for the events of 1969, this Christopher Street dive would be an unlikely choice for New York’s LGBTQ epicenter. The bar is an unassuming queer haunt located in Greenwich Village with a simple brick facade and a cozy wood-panel interior. But Stonewall isn’t just a bar — it’s a cornerstone of queer culture, a call to action, and an idea that continues to ignite change around the world.

In 2000, the Stonewall Inn became the first National Historic Landmark commemorated for its importance to LGBTQ history. In 2016, it became the National Park System’s first LGBTQ monument.

2. Cherry Grove Community House and Theater — Fire Island, New York

Cherry Grove, a tiny town tucked in between Fire Island’s rolling dunes and maritime forests, is well known as one of the world’s hottest seasonal destinations for LGBTQ travelers; it also happens to be one of the most important. In the 1930s and 1940s, queer folx found sanctuary on this isolated sandbar and began building the first gay and lesbian enclave in the US. Although there were occasional police raids for “lewd behavior” and same-sex sexual activity, Cherry Grove essentially provided what the country’s forefathers promised nearly two centuries prior: freedom.

Cherry Grove Community House and Theatre, a site that has served as both civic center and performance space since opening in 1944, is integral to understanding queerness in the US. Unlike the gayborhoods forming in major metropoles in San Francisco and Chicago at the time, LGBTQ residents in bucolic Cherry Grove were openly integrated with straight residents and helped govern local life. The Community House and Theatre became a place where LGBTQ people safely experienced what it’s like to live without hiding their identities — a vital precursor to the gay liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s. The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2013.

Throughout summer, locals can still enjoy a roster of community-oriented events in the historic building, including live performances, yoga classes, Al-Anon meetings, and church services.

3. Vicksburg National Military Park — Vicksburg, Mississippi

Photo: Chris Higgins Photography/Shutterstock

After introducing anti-trans legislation in March, the “Hospitality State” might not seem so hospitable to trans people, but in 1906, Mississippi erected a national monument honoring a man who would likely identify as trans today.

In the summer of 1863, Union forces defeated Confederate soldiers in Vicksburg after starving them out during a 47-day siege — a victory seen as a decisive turning point in the Civil War. Vicksburg National Military Park commemorates the events with 1,325 markers, including the Illinois Monument — a marble fortress bearing the names of 36,325 participating soldiers from Illinois.

One of these names is Albert Cashier — the shortest Private enrolled in the 95th Illinois Infantry. Cashier, born Jennie Hodgers and assigned female at birth, enlisted in the Union army as a male in 1862 and served in upwards of forty Civil War battles. After the war, Cashier continued identifying as a man and enjoyed privileges denied to women at the time. He held various jobs in manual labor, collected a veteran’s pension, and even voted in elections.

After admittance to a veteran’s hospital following an injury, Cashier’s secret was made public. Although members from the 95th came to his defense, he was sent to a mental institution and forced to wear women’s clothing until he died in 1915.

Albert Cashier is one of roughly 400 people who were assigned female at birth and enlisted as a man to fight in the Civil War. His legacy laughs in the face of both Mississippi’s recent legislation and the draconian trans military ban repealed by the Biden administration in early 2021.

4. Edificio Comunidad de Orgullo Gay de Puerto Rico — San Juan, Puerto Rico

The gray facade of 3 Saldaña Street in San Juan, Puerto Rico, might seem drab from the outside, but inside the Mediterranean-style apartment complex, a colorful history unfolded. Between 1974 and 1976, Edificio Comunidad de Orgullo Gay de Puerto Rico, commonly known as Casa Orgulllo, used the apartment complex as the site of Puerto Rico’s first gay liberation organization. Inspired by the 1969 Stonewall Uprising, Casa Orgullo fought for LGBTQ rights through a mix of political lobbying, educational programming, and social outreach. Although the group disbanded in 1976, its impact on the local LGBTQ community was long-lasting. The National Register of Historic Places added Casa Orgullo to its list in 2016.

Today, travelers will find that San Juan’s LGBTQ community is enjoying a real-estate upgrade. In the past fifty years, queer folx migrated far from the dull house in Santa Rita to colorful beachfront properties in Condado — a trendy destination next to Old San Juan favored by tourists and locals alike.

5. Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument — Crow Agency, Montana

Photo: Don Mammoser/Shutterstock

In June 1876, 263 American soldiers, led by Lt. Col. George A. Custer, lost their lives while fighting an army of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors in the Battle of Little Bighorn. The decisive Indigenous victory was one of the last times Native people successfully fought to preserve their way of life in the US.

The site was named a national cemetery in 1879. Two years later, the government added a memorial for Custer and his men. “Custer’s Last Stand” is a popular nickname for the battle, and most historic literature focuses on his leadership and loss instead of the Indigenous lives he threatened.

It wasn’t until 1991 that the US Congress proposed a similar memorial for Indigenous tribes, and today, reclamation efforts highlight a powerful piece of LGBTQ+ history. Cheyenne male Two-Spirits, known as he’emane’o, played essential roles in celebrating battle victories and likely led their tribe in honoring the events of 1876.

Two-Spirit refers to an Indigenous person who embodies both masculine and feminine qualities. It’s a revered spiritual and societal role held by queer tribe members. Now, while examining the ravines and bluffs around this national monument, visitors can imagine an America that praised people outside the male-female gender binary — a way of life that queer communities are currently trying to restore.

6. The Clubhouse — Washington, DC

DuPont Circle emerged as Washington DCs go-to gayborhood in the mid 20th century with gay-centric bookstores, activist organizations, and bars. But because of racist attitudes and discrimination, there’s something the neighborhood lacked — queer people of color.

As a result, a social club for Black queer locals known as the Metropolitan Capitolites began throwing inclusive parties in their homes in the 1960s. By 1974, the group outgrew their house parties and opened two bars — both too small to capacitate the clamoring crowds — and were on the lookout for a bigger space. That’s when they found a single-story, L-shaped building at 1296 Upshur St, NW–20-minutes north of White-dominated DuPont Circle. For the next 15 years, this building became a nationally-renowned dance hall and community center for Black LGBTQ folx. It was dubbed ClubHouse.

Legends like Patti Labelle, the Weather Girls, and Sylvester graced the venue’s stage. Ballet icon Rudolf Nureyev purportedly spent a night dancing with patrons until dawn. The same engineers behind Studio 54 set up the sound system, and for nearly a decade, this after-hours nightclub enjoyed an equally glamorous reputation.

In the 1980s, as the AIDS epidemic devastated queer communities, ClubHouse became a site for activism and support. Us Helping Us — a group providing holistic health assistance to people living with HIV/AIDS — met at the ClubHouse until the establishment closed in 1990. The group is still one of DC’s most important Black-centered HIV/AIDS education and support organizations; the Historic American Buildings Survey added ClubHouse to its roster in 2016.

Although the dance floor is currently empty and the building in disrepair, its legacy lives on in events like DC Black Pride — a modern reminder that if someone doesn’t make space for you at their party, throw a party for yourself.

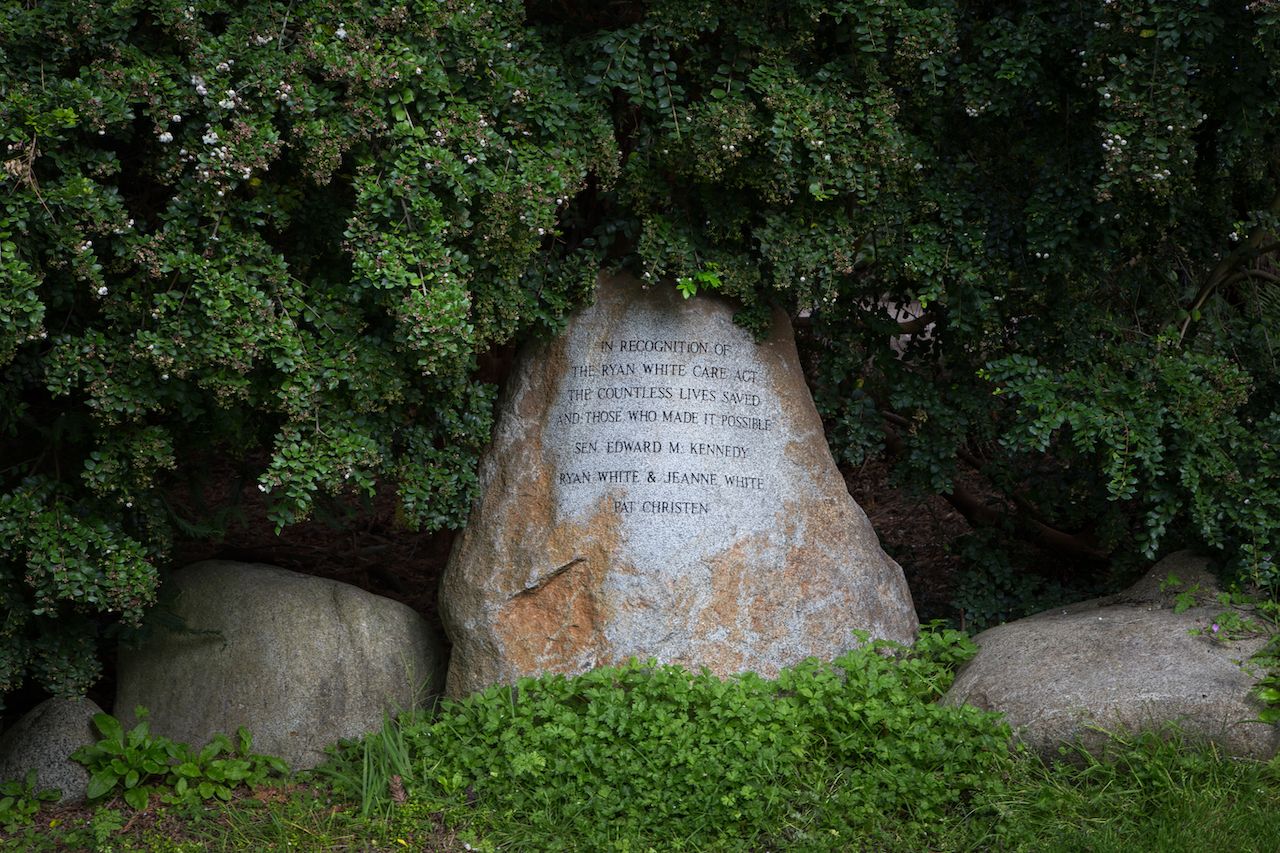

7. National AIDS Memorial Grove — San Francisco, California

Photo: Ken Wolter/Shutterstock

Golden Gate Park, an expansive 1013-acre green space stretching from Ocean Beach to Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco, has been sacred to LGBTQ residents for decades. In 1970, a park “gay-in” following the city’s first gay rights march solidified San Francisco’s annual Pride celebration. A Dutch windmill in the park’s western corner once served as a popular cruising location. The inaugural Gay Games took place here in 1982, and iconically queer “Tales of the City” and “Looking” both feature the park in their respective series.

It’s no wonder, then, why LGBTQ activists and allies chose this location to create a living memorial honoring people impacted by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Queer folx have a long history of calling these hallowed grounds home.

The National AIDS Memorial Grove was conceived in 1988 and federally designated as a national monument in 1996. According to the CDC, over one million Americans currently live with HIV, and over 50% of new infections come from male-to-male sexual contact. This government-sanctioned space provides the disproportionately affected LGBTQ community a safe place to reflect upon the ongoing health crisis and continue the arduous healing process.