When my friends learned I was traveling to Morocco, the most common piece of advice was, “don’t get scammed.” None of them had been to Africa or knew anyone from the country, and were basing their jovial warnings on fairly limited knowledge of the country. Yes, there have been some recent stories about unfair taxi pricing and common tricks merchants use to earn a couple extra dirhams. However, according to the US State Department, Morocco has only a “Level 2” travel warning — the same rating as countries like Sweden, Kenya, France, and even Antarctica. Unfortunately, many travelers rate countries considered foreign (a.k.a., non-Western) inherently less safe, whether or not the data backs it up.

Mint Tea, Music, and Mistaken Arabic: A Week in Morocco for First Timers

After chatting with my friends more, I learned that they were confusing the customs and culture of Morocco — a country in North Africa, and a shorter flight time from New York City than Paris, France — with completely unrelated Middle Eastern countries. But since I’d not yet been to Morocco, I didn’t have personal experience to convincingly refute their impressions.

In June, I took a small group trip to Morocco, landing at Casablanca’s Mohammed V International Airport. Over the next week, we visited Marrakech, Rabat, and Tangier with a hired driver, and even spent a few days at Mawazine Rabat, the largest music festival in Africa.

The author visited Marrakech, Rabat, Casablanca, and the Agafay Desert Photo: Museum of Jewelry, Rabat

While having a dedicated driver made our trip easier than trying to arrange our own transportation, I was still surprised by the relative ease of travel in the country, and general friendliness of nearly everyone we met. No one would say Morocco is as easy to visit as a country more similar to the US, like Canada or Ireland, but I returned from the country with more than just my spoils from the markets (a cool oil print, and jars of turmeric and saffron). Just a week of travel gave me a good sense of what it’s like to visit Morocco, helped me better understand the fascinating blend of cultures throughout North Africa, and showed me just how friendly locals can be when you open yourself to connections.

For travelers keen to dip their toes into the culture of North Africa, Morocco is a warm and welcoming place to start.

It’s easy to feel like family

Morocco’s art, culture, and architecture reflect a diverse range of ethnicities and heritages. Photo: Morad.onto/Shutterstock

As a white American, I expected to feel a little adrift in an unfamiliar Arab-speaking country. But it’s tough to feel lost in a place as culturally multifarious as you are, and I felt as at home in Morocco as I have in any other country. That’s probably because, like me, Morocco is a blend of cultures and ethnicities.

Throughout its history, the country has been a crossroads of several civilizations, ruled by Romans, Arabs, and Amazigh (formerly called “Berbers”), and colonized by the French and Spanish. As the first inhabitants of North Africa, Amazigh are considered Morocco’s Indigenous people, and today, Arab-Amazigh make up the largest ethnic group. Between the 15th and 17th centuries, after the Christian conquest of Spain, Muslim and Jewish exiles poured into Morocco, bringing Andalusian influences to the country’s architecture, music, and food. There’s an intriguing history lesson around every corner, if you’re looking for it.

I quickly learned that the diversity in the country means fewer people feel like outsiders, and most people I met seemed eager to both introduce me to their multi-textured cultural tapestry, and learn about mine.

I arrived at the airport in Casablanca on a Monday morning, and went outside to meet Ibrahim, our driver and guide.

“Welcome, brother,” he said. “Let’s go, let’s go. Ibrahim is never late.” Never mind that he had been 10 minutes late picking me up. And yes, he referred to himself in the third person.

A Amazigh guide originally from a Saharan desert village called Merzouga, Ibrahim was constantly adjusting his black-framed glasses, and regaling me with his best American accent. On my first full day, after driving to Marrakech, he dropped me off on the outskirts of the Medina: the old part of town famous for its sprawling souk (market).

Overcoming preconceived notions in the Marrakech Medina

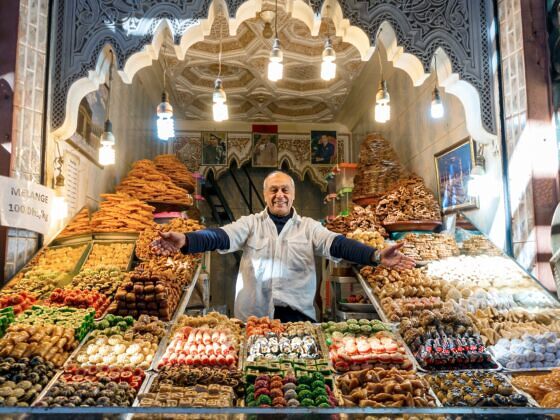

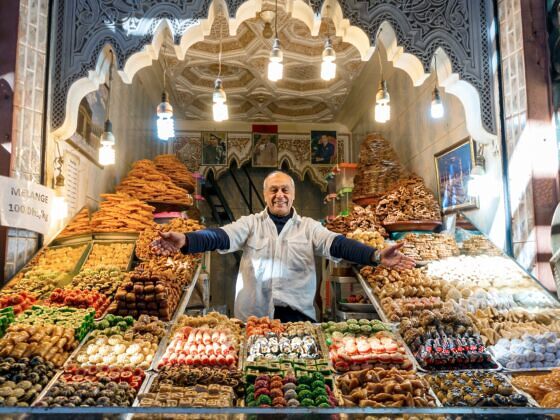

Photo: Min Jing/Shutterstock

The labyrinthine souk of Marrakech dates back to the 11th century, but it doesn’t feel like stepping back in time so much as stepping sideways, into a stone-laid bazaar with timeless rules and newly crafted wares. In an enthralling blend of ancient and modern, visitors will have to keep an eye out for locals whizzing down the narrow lanes on motorbikes, as well as donkeys meandering by with loads of produce piled on their backs.

When a handmade oil drawing of a minaret at sunset caught my eye, I felt a rush of nerves. I wasn’t sure I had the skill to haggle. The sheer volume of products felt overwhelming, as did the prospect of a tense back-and-forth with a skilled haggler. I knew the close quarters and crowded souks of the Medina meant travelers sometimes get overcharged and pressured, and my friends’ concerns rang in my ears. But it turns out, haggling can actually be fun.

The artist was a middle-aged man in a blue robe, who shook my hand and gave me his price. My spontaneously-devised strategy was to act aghast at the initial price and pretend to leave, wait for his counteroffer, and go from there. I was nervous, but the seller actually seemed like he enjoyed the back and forth. As I prepared to leave, oil drawing and 50 percent discount in hand, he touched my shoulder and asked where I was from.

Photo: Maria Albi/Shutterstock

When I told him I was from Boston, he said, “Boston Celtics!” and pretended to dribble and shoot a basketball. “World champions!” I asked, surprised, if he watched NBA games.

“Some,” he said. “I like LeBron James. He must retire soon, I think. He is older than me, but has a better slam dunk.”

It was an encounter that made me rethink what had been stressing me out about visiting the souks. When he touched my shoulder, I thought at first it’d be to try to sell me another painting. But he was merely curious about what brought me to Morocco, and eager to talk basketball with another fan.

Later that day in the market, a dyer spent 30 minutes indulging my questions on how the fabric dyeing process works and how colors are made, while simultaneously asking me questions about how clothes are colored in the US (I embarrassingly had no idea). He was a scarf maker from a long line of scarf makers, and proudly showed off his products while also sharing a hearty helping of family history. We chatted, as he was curious about my job, and thought it was unusual that more American children don’t go into the same business as their parents.

“You made a good deal,” Ibrahim said when I returned to the car and told him about my oil print. “Now you are ‘ayela’ here in Morocco. That means family.”

While “family” felt like an exaggeration, I certainly appreciated the shopkeepers’ conversation and welcoming energy. The souk will be different for every traveler – that’s part of its centuries-old mystique – and I certainly can’t responsibly suggest that every experience will be positive. The shopkeepers want to make money, and are fairly aggressive in their pursuit of it. But in my wanderings through the souk, merchants had a genuine curiosity about foreigners and were eager to make a connection.

I felt truly welcomed at hotels and restaurants

Photo: Mykola Ivashchenko/Shutterstock

If you think you need to be in a major US or European city to take advantage of five-star luxury, you haven’t experienced Marrakech or Rabat’s extravagant hotels and six-star service (if six stars are even possible). Both at the palatial Oberoi Hotel on the outskirts of Marrakech, and the Fairmont Residences La Marina Rabat-Sale in Rabat, it felt like the staff must have studied index cards of every guest. They immediately knew our names and greeted us warmly whenever we walked in. At the Oberoi, the staff even left little personalized touches around our rooms during the cleaning service: they noticed a book on my bedside table and gifted me a bookmark, while a woman traveling with me returned to her room one afternoon to find a fresh tube of toothpaste beside her nearly empty one. They were every bit as luxurious as pricier hotels in trendy destinations like Ibiza or Bali.

Photo: The Oberoi Marrakech

It wasn’t just hotels where hospitality felt natural, but in many restaurants, too. I actually felt the most at home in Morocco whenever I entered a restaurant, because the chefs and hosts made me feel like I was at a friend’s house, with that friend excited to cook their family recipe for me.

In my experience, Moroccans seemed to love serving their guests food as much as this particular guest loved eating it. In asking why that was, I learned for many Moroccans, it stems from the link between food and community. Dishes are often served family-style, set on the table in large portions guests can scoop onto their plates. Eating meals is an excuse to be social in Moroccan culture, making it easy to feel at home.

I noticed an intentionally welcoming atmosphere outside of traditional restaurants and hotels, too. During a dinner at The White Camel, a tented camp in the Agafay Desert, I doubt even a professional eater could finish all the food served to my table. That night, we enjoyed tagine, an assortment of salads, and lham bel barkouk (beef and prunes). Other dishes commonly served include briouats (crispy pastries often filled with meat), taktouka (a salad of tomatoes and peppers), and lentil soup, not to mention couscous and mint tea, which always seem endless. If the impressive spread wasn’t welcoming enough, the troupe of Amazigh musicians playing Moroccan-inspired blues music in the background helped, as they were clearly happy to be putting on a show.

Photo: Bruno M Photographie/Shutterstock

“How was everything?” the waiter asked at the end.

“Wonderful. Especially the lham bel badook,” I said, in a horrible mispronunciation of “barkouk.” Confused, our waiter looked at me, then to Ibrahim, who was doubled over in laughter at my poor attempt to speak Arabic.

Thankfully, we were interrupted by a fire dancer, who ushered us outside. He stood on a plateau overlooking the vast desert, skillfully twirling flaming batons closer to his body than should be legal and sending embers flying into the black desert night.

At this point, I had a sudden realization that it wasn’t just the food that exemplified the culture of hospitality, but also, the way in which locals were enthusiastic about sharing Moroccan culture with guests. This probably explained why dinners were often leisurely three or four hours long. That was even true at luxury restaurants like La Grande Table Morocaine inside the opulent Royal Mansour Marrakech. Unlike some American restaurants, which rely on quick turnover and maximizing the number of meals served per night, the focus seems more to be on a slow pace and connecting with the people around you (and trying as much food as possible).

People in the tourism industry seemed happy to connect everywhere I went

Photo: muratart/Shutterstock

I ended my trip in Rabat, Morocco’s capital city about a three-hour drive from Marrakech. In the middle of the city’s white-and-blue-hued Medina, evocative of Santorini’s whitewashed Cycladic aesthetic, I found Riad Dar Chrifa, a modern and opulent riad (a hotel centered around a courtyard) inspired by traditional, luxurious design.

A birdcage with an African Grey parrot sat in the corner, drawing most people’s curiosity, but the light illuminating my chicken b’stila from the skylight was capturing my attention. The dish certainly deserved the spotlight. A pie stuffed with savory chicken and cinnamon, and lightly coated with powdered sugar, it’s a dessert that masquerades as a hearty entrée. It’s one of the many reasons I didn’t feel guilty eating what felt like two pounds of it.

During the meal, the waiter came up to me. “You look like my cousin, Ismail,” he said with a nudge. “He likes b’stila, too.”

“Well,” I replied between bites, “he must be a handsome guy.”

“No,” laughed the waiter. “Not really.”

The author (right) and driver Ibrahim (left) with a pet parrot at Dar Chrifa. Photo: Eben Diskin

We both chuckled, and he spent the next 10 minutes telling me about his cousin and trying to convince me we looked alike, showing me a photo of a parrot sitting on his cousin’s shoulder. As though struck by a brilliant idea, he suddenly opened the birdcage and transferred the parrot to my shoulder, where it squawked some unintelligible remarks at me.

“I bet even he can say ‘lham bel barkouk,’” Ibrahim teased. He told me African Grays are extremely intelligent, and can reach the cognitive level of a 5-year-old human.

I appreciated that Dar Chrifa didn’t take itself too seriously, giving me another chance to experience meals the way Moroccans do: as a time to be present with family and friends, and take pleasure in conversation, fun, and diversion.

Even major social events felt more welcoming

Photo: Mawazine Music Festival

One thing you definitely don’t want to be late for is Mawazine Rabat, Africa’s largest music festival by attendance. Past headliners include world-renowned artists like David Guetta, The Weeknd, and Travis Scott, as well as homegrown Moroccan artists, spread across six stages throughout the city. That means no matter where you are in Rabat, you can’t escape the thumping beats or festival vibes (not that you’d want to).

Though I wasn’t able to catch 50 Cent or Will Smith (yes, that Will Smith) at this year’s festival, I did manage to see Lost Frequencies, who drew a crowd every bit as lively as those at Tomorrowland, one of the largest EDM festivals in the world.

What makes Mawazine stand out from events like Tomorrowland, however, is that all the acts are completely free. In a world where seeing your favorite artists usually costs three months’ rent, Mawazine does away with ticketing. Rather than waiting in line for hours and enduring the indignities of security only for nosebleed seats that require binoculars, guests just wander into the park or onto the beach, and find a spot in the crowd. It seemed like another decision designed to ensure that all feel welcome. Crowds are made up of people from all kinds of economic backgrounds, all gathered to enjoy music from around the world.

In my case, I was able to join a huge crowd of Moroccans on the beach, losing myself in the jumping, chanting masses without for a moment feeling out of place.

Finding connections outside of the tourism scene

Photo: Hyserb/Shutterstock

A Moroccan friend of mine once told me that whenever she returns to Morocco for a quick visit, she finds what she calls a “Moroccan boyfriend:” someone she casually meets at a bar or other social situation. She’ll spend the week hanging out with that person most days, usually in groups with a collection of siblings or friends. The ease with which she was able to do that inspired me to try to make my own personal connection, and while in Rabat, I started swiping on Hinge.

Dating apps can be a great way to meet local people, whether it’s to grab a drink, have some company while visiting a tourist attraction you’ve always wanted to see, or even finding a cool sight usually limited to just locals. Given the cultural proclivity for spontaneity, and openness to meeting new people, I guess I wasn’t too surprised when Samira from Hinge agreed to meet me at the Mohammed VI Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rabat. I can’t pretend I fully understood the artwork, but I enjoyed a great afternoon.

While there, I thought of my friends, sitting at home and wondering if I had gotten “scammed” in Morocco. I wasn’t sure if they were going to believe me when I told them about what felt to me like authentic connections with the people I met. I wondered if they’d be surprised to hear that it took less than a week for a Moroccan to tell me I was like family – even if I still can’t pronounce lham bel barkouk.

If you go: Morocco trip planning tips

Photo: YASTAJ/Shutterstock

Though Morocco might feel culturally distant for many US travelers, there are several nonstop routes from the US with a flight time of under eight hours. United Airlines flies between NYC and Marrakech, and Royal Air Maroc flies from NYC, Miami, and Washington, DC, to Casablanca.

Ubers and rideshares aren’t available in Morocco (yet), but taxis are available in all major cities at a reasonable price. Just make sure the cab is marked with a taxi company logo, and fare is calculated via the meter. Concierges at most hotels will also be happy to call a taxi for you from a reputable company. Most travelers doing cross-country trips arrange drivers for the longer segments, as Moroccan drivers tend to be a bit more aggressive than most Americans are used to. That said, you can rent cars at the airport, and most roads are in good condition and easily navigable.

Trains are also a great way to get around Morocco’s major cities while seeing more of the country. Thanks to the new high-speed Al Boraq train, you can get between Rabat and Tangier in just under an hour and a half. It’s a journey that used to take five hours.