If the past year has taught us anything, it’s that spending time outdoors is an escape that keeps us sane even in the toughest of times. The Norwegians have a term for this: friluftsliv. Pronounced free-loofts-liv, it loosely translates to “free air life.” It’s all-encompassing and can be widely interpreted. In winter, your idea of living life free of indoor confinement could be to quietly ice fish on a nearby frozen lake while a friend’s ideal scenario might be to strap on crampons and summit an icy peak. These very different activities both represent the “free air life” ethos.

Norway’s Friluftsliv Is Like Hygge for Outdoor Lovers

As an American, I was curious if one can also channel the Norwegian spirit of friluftsliv through the power of prose? What if there was a book that evoked the spirit of the term nearly as well as the outdoors itself?

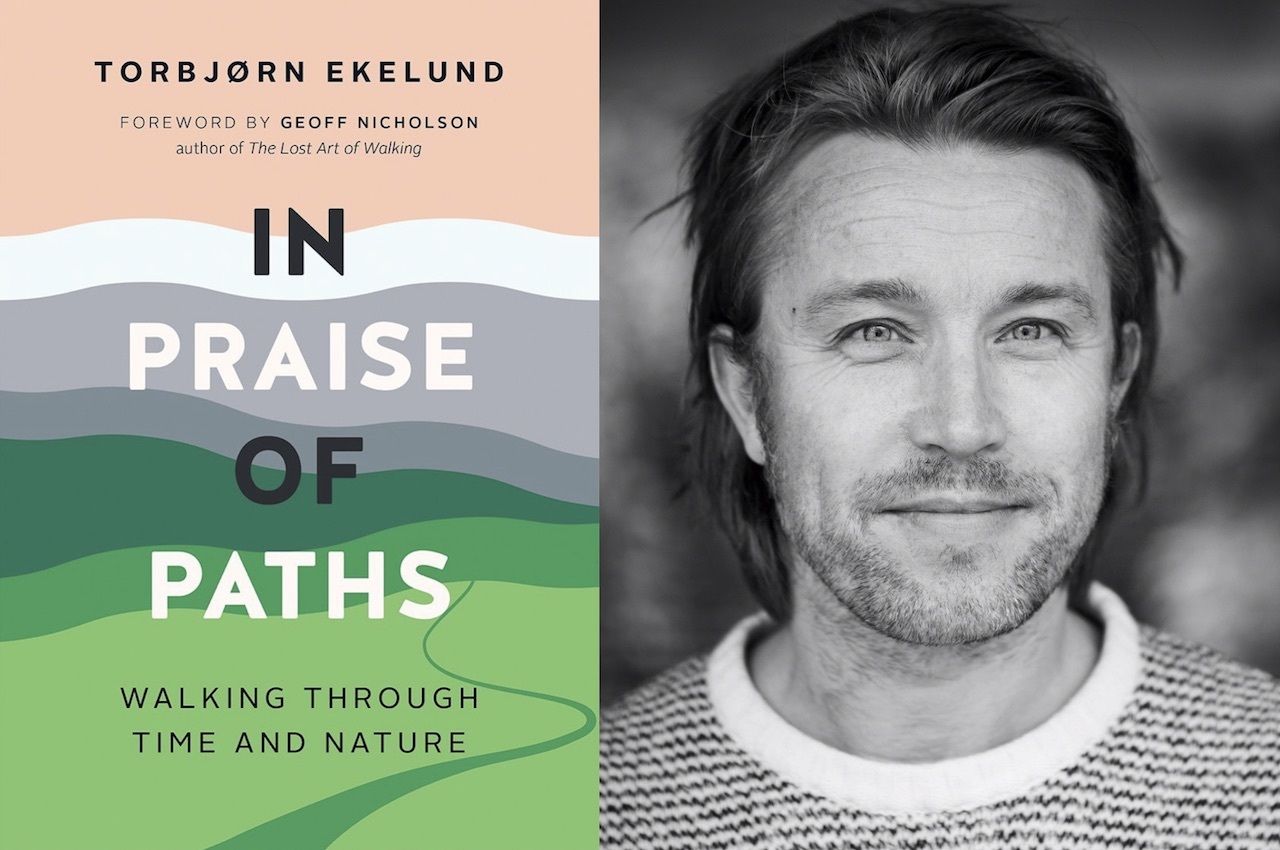

If so, then a top contender would be In Praise of Paths: Walking Through Time and Nature by Norwegian journalist and author Torbjørn Ekelund. An evocative personal narrative of time spent wandering through natural surroundings, In Praise of Paths perfectly captures the friluftsliv spirit, at least as I understood it. Ekelund recounts a wooded path from his childhood, showing how walking helped Ekeland cope with an epilepsy diagnosis that stripped him of his ability to safely drive a car and, more broadly, how nature can help us to find identity. Other paths appear throughout the book, some only metaphorical, all tying into the friluftsliv on which Ekelund has prioritized many of his life’s major decisions.

The book got me wondering how those of us on the other side of the Atlantic might add more friluftsliv into our lives. So I spoke with Ekelund to get his thoughts on the term’s meaning, how to achieve it, and on whether my outsider’s hypothesis that one could get frutisliv from a book was at all justified.

What friluftsliv means and how to capture its spirit this winter

Photo: everst/Shutterstock

“I’ve figured out that the story about travel is, in many ways, what you remember when you get home,” Ekelund told me over Zoom, adding that not only does he not write while traveling, but he also seldom even stops to jot down notes while on his frequent strolls. “When you walk along a trail or whatever kind of traveling you do, it disturbs the ability to observe,” he says.

Friluftsliv is to Ekelund not so much something you strive for but rather a fact of life, so long as some of said life is spent outdoors.

“It’s a word everybody [in Norway] is very familiar with. It means spending time in nature, without doing anything in particular. So if you go skiing, or if you go hunting or fishing, or just walking, everything is friluftsliv.”

My idea that prose could bring the friluftsliv spirit to life withered the further we got into our conversation. It became clear that to achieve friluftsliv, no book — no matter how adeptly it evokes nature’s beauty and power — can replace actually spending time outdoors.

“But [friluftsliv] has another meaning as well, which basically is to spend time in nature, which is synonymous with spending time away from the ‘normal’ life of city and work or whatever,” says Ekelund.

Photo: Greystone Books + Marte Garmann

The COVID-19 pandemic has accentuated this, Ekelund notes, as there hasn’t been much else to do — in Norway or any other place. “In my neighborhood here, which is in the outskirts of Oslo, people were walking all over the place all the time. They had fires in their gardens in the evenings, and I’ve spent a lot more time outside during this time.”

In winter, this often manifests itself as cross-country skiing. Ekelund is also very fond of winter camping, sans-tent, sleeping only underneath a tarp tied to surrounding trees, with a fire for warmth.

“In -14 Celsius, it gets really cold, so what you have to do is figure out not how to survive but how to manage and make it as comfortable as possible,” he says. “You learn a lot about nature when you do it. It’s learning by doing. I really enjoy that kind of friluftsliv when you’re trying to figure out how to manage life in nature.”

The takeaway for those of us who prefer tarp-covered slumber in warmer climes is that winter friluftsliv might take a bit more effort than that of warmer seasons, but it’s that effort that makes it worth it. Just get out there — on snowshoes, on cross-country skis, in a tent, or on the chairlift, and let your mind slip away from daily stressors.

How to friluftsliv to your life if you live in a city

“The first thing to start with is to start looking more around you,” Ekelund says. “There’s nature all around, even in the centers of big cities. Central Park in New York is probably bigger than most forests in the area around my city. Try to observe and see even the tiny places.”

Even if you do live in a city, all it takes is a willingness to walk out your front door and look up. The birds, the trees — enjoying anything natural is inherently friluftsliv. If possible, spend the night somewhere, even if that somewhere is a few minutes away from your home. “Spending a night outside makes everything more exotic,” Ekelund says. “Maybe you’re a bit scared of the dark, maybe it’s a bit spooky, you’re not quite sure what equipment to bring. But if you do it once, you will learn a lot, so when you do it the second time, you will feel a lot more experienced.”

Adding friluftsliv into your lifestyle then becomes something that gets easier the more you do it and becomes ingrained in you, kind of like how to flip an egg or ride a bike. Don’t be intimidated; just go.

“It’s easy to think of nature as something big and undisturbed, but still there are things going on everywhere,” Ekelund says.

Develop a mindset of conservation

Back to my query from above, I learned from speaking with Ekelund that there is one way to add more friluftsliv into your life even when you aren’t outdoors: maintain a focus on conservation.

“At a very early age, both my parents and my grandparents taught me about being respectful when you’re traveling in nature,” Ekelund says. “So when all this became more urgent in the past 10 years with climate change, it was a very natural thing for me, a thing I’ve always thought about. It has to do with a view of nature and our place in it.”

One should, he adds, have respect for all living things and be observant when it comes to the small things in nature. Ekelund brings this to life through a digital publication he co-founded along with three other veteran Norwegian journalists, Harvest. The website focuses on outdoor recreation and conservation issues in Norway and came to life largely due to its founders’ pursuits of friluftsliv — fly fishing in Ekelund’s case — as he wanted to better tell the stories of the sport he loves.

In the United States, we’re fortunate to have millions of acres of public lands to enjoy, along with state and neighborhood parks, even down to the walking path behind our home. Friluftsliv itself will always be an outdoors pursuit — but the power of prose and a book as thought-provoking as In Praise of Paths can help inspire us to get out there. After all, we all have to start somewhere.