Darmon Richter is Chernobyl-obsessed. He took his first trip to Chernobyl in 2013 as part of a licenced tour, and has been leading and designing tours of the Exclusion Zone since 2016. In total, he’s visited Chernobyl 20 times on multiple day trips, including once illegally with a “stalker” — as those who visit the area illegally are known — as his guide.

This Photographer Took an Illegal Tour of Chernobyl. Here’s What He Saw.

“After that first visit, I don’t know if I necessarily would have wanted to go back to Chernobyl again,” he explains during an interview with Matador Network. “The tour experience that I had wasn’t mind-blowing. It was quite sensational. We had a large group of 30 people being rushed about to rooms and abandoned buildings with various dolls, gas masks, and all these props set up that felt somehow inauthentic.”

Photo: Darmon Richter

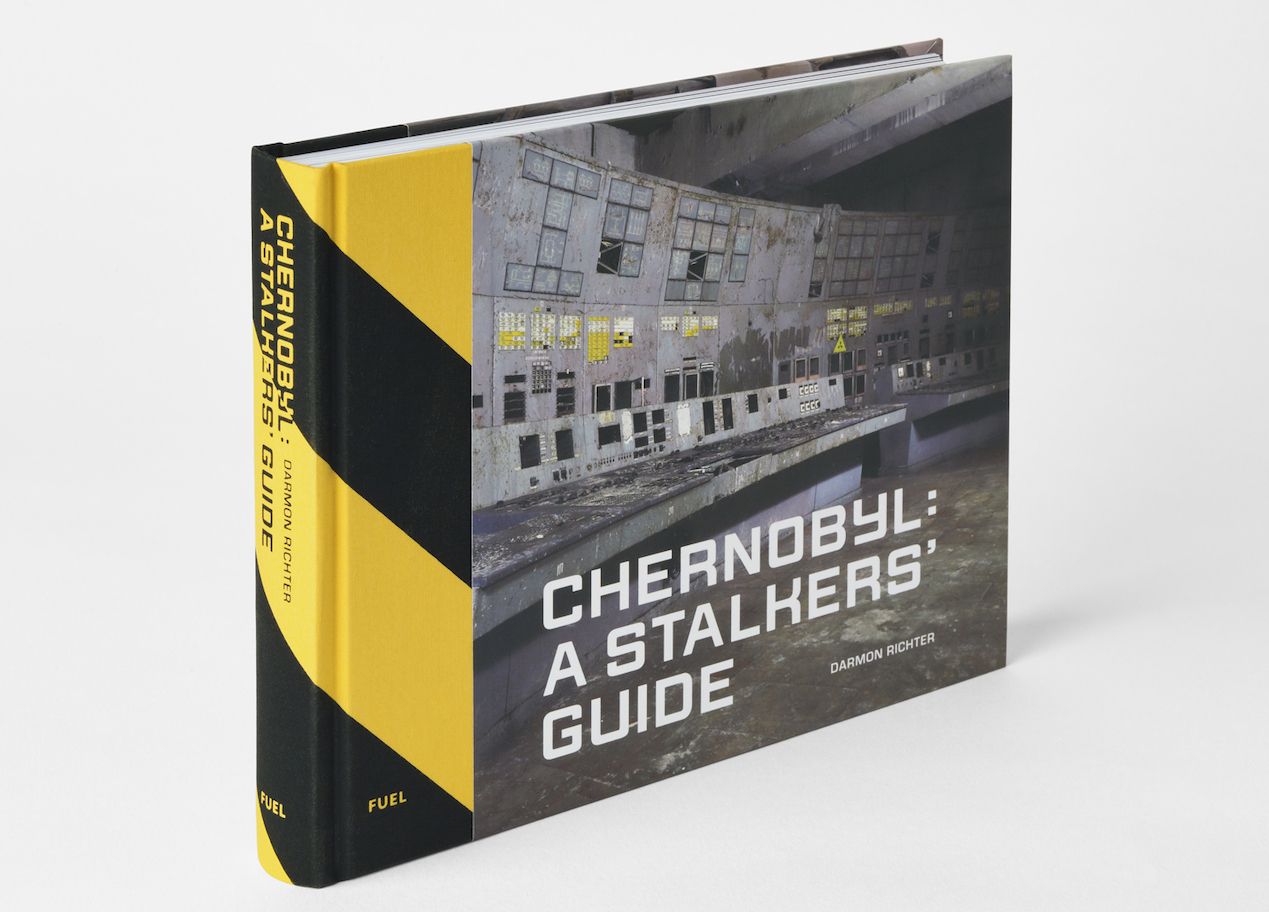

But after spending more time in Ukraine and getting to know people who work in the tourism industry in Chernobyl, he got increasingly interested in the past and present of the evacuation zone. Throughout the years and the many visits, he gathered enough expert knowledge to write Chernobyl: A Stalkers’ Guide, a recently published photo guide-cum-travelogue that takes readers way beyond the clichés most of us have of the area.

Photo: FUEL Publishing

Taking an licensed tour is an exclusive experience reserved almost entirely to foreigners who don’t think twice about dropping $100-$200 for a day visit. And they do it in larger and larger numbers each year; in 2019, 124,000 visitors took an official tour of Chernobyl. But for the less-financially privileged locals whose country has been forever changed by the nuclear accident, and who grew up in the shadow of Chernobyl, there’s one much more affordable way to see this place for themselves and witness their own history — hopping the fence.

“If anyone has any right to be curious and to want to see this place first hand, it’s the people living immediately around it,” explains Richter. “For a lot of young Ukrainians it becomes almost like a rite of passage. There’s a huge draw [for them] to engage with this place and, for many, it’s easier to sneak in than to pay for a tour.”

Photo: Darmon Richter

When Richter, a British writer and photographer, decided to take an illegal tour of Chernobyl, it was not to seek an adrenaline rush or to be rebellious — he wanted to get a better picture of the place.

“[The Ukrainian Exclusion Zone] is a huge area. It is around 1,000 square miles and there used to be almost 100 villages within it, but after looking at maps while designing tours, I realized that the area where the tour buses go is tiny, so I got curious.”

Photo: Darmon Richter

Richter was able to find someone to take him on an illegal visit to the Exclusion Zone through a friend of a friend, but even without that connection, it would have been easy enough for him to find a stalker to guide him. There are public blogs with accounts and photographs of unofficial visits online for everyone to see, and many of those bloggers are open to chat about what they do. The person with whom Richter went has a website on which they sell illegal tours.

Surprisingly, those very public stalkers are confident Ukrainian authorities do not check their online goings-on. “They’re trying to catch people in the act rather than stop them before they transgress. It’s a very outdated model, though with the increased attention on Chernobyl today, it now seems to be changing — the Ukrainian government is currently discussing new legislation, which would change trespass in the Zone from a civil, to a criminal offence.”

Currently, the consequences of being caught without authorization in the Ukrainian evacuated zone are milder than one might imagine. If authorities catch visitors on foot, wandering around with a camera, exploring for the sake of sight-seeing, the fine is akin to a slap on the wrist — $25 and a drive back to the checkpoint is hardly a deterrent. (Richter mentions that for those who roam the area in order to loot metal, poach animals, or cross the unmanned Ukrainian-Belarus border, it’s another story — the punishments are much more severe.) However if this new legislation passes, the fines will go up by a hundred times, and those caught will receive a permanent criminal record — which for Ukraine’s stalker community, is liable to feel like the end of an era.

And contrary to what most of us think, the evacuated zones, whether in Ukraine or Belarus, are not heavily guarded. The tourist entrance is highly secure, with a fence and checkpoints where armed guards check visitors’ passports and tickets, but there are many places where there are no barriers and entering undetected is easy.

During his one and only illegal visit to Chernobyl, Richter penetrated the Exclusion Zone by wading through the Uzh River which forms a natural border with the rest of Ukraine. And while it was easy enough to enter, once inside, it was no picnic. For four exhausting days, Richter and other stalkers slept roughly in small disused houses during the day and hiked throughout the nights; they constantly hid from people and checked for radiation levels; they worried about getting caught; they were scared of falling through the floors of the abandoned buildings they explored, and getting attacked by the wolves who live in the zone today.

“I would not do it again,” says Richter, “and I certainly don’t want to encourage people to travel to another country and break the law. They are many things that could go wrong during an illegal tour.”

Photo: Darmon Richter

Not all licensed tours resemble the one Richter first took and despite what the title of his book might suggest, he does not believe that an illegal tour of the Exclusion Zone is the only or best way to see Chernobyl in an interesting, novel light. As a tour organizer, he thrives to take visitors further afield and find unusual lodgings, canteens, and places to see such as log cabins, beautiful abandoned Orthodox churches, murals, inhabited villages, WWII memorials, etc. He wants to show visitors that Chernobyl should not be restricted to the morbid appeal of the former control room or Pripyat’s rusty ferris wheel — he wants to make sure everyone knows that it was an interesting and beautiful place way before 1986 and that it continues to be so.

Photo: Darmon Richter

“Did you know that tourists only account for five percent of the total human traffic into the zone?” Richter asks during our conversation. “You have thousands of people working at the power plant, and many more working in forestry, conservation, construction, etc. and many of them come in by train into the zone. The place is a hive of activity.” Then he mentions that there are helicopters, small planes, and kayaking tours of the Exclusion Zone before explaining that Chernobyl was home to a large traditional Hasidic Jewish community before the horrors of the Shoah.

These are the kind of golden nuggets of information you get from Richter, who has become an expert on Chernobyl, and there’s plenty more to learn in the 40,000 words and over 100 beautiful photos that comprise his fascinating book. So, before you make any decision on whether or not you want to visit Chernobyl, and how you want to do it, pick up Chernobyl: A Stalker’s Guide and dive into the wealth of revelations and adrenaline-inducing narratives he’s packed in it.