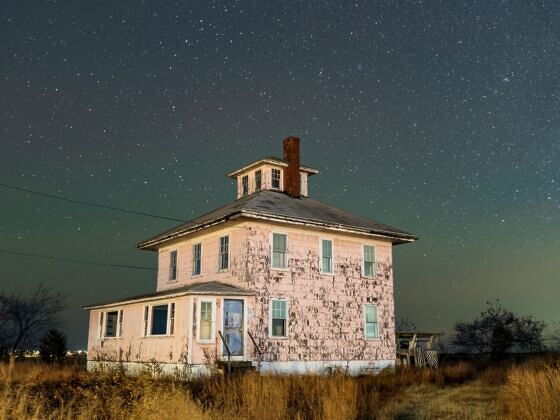

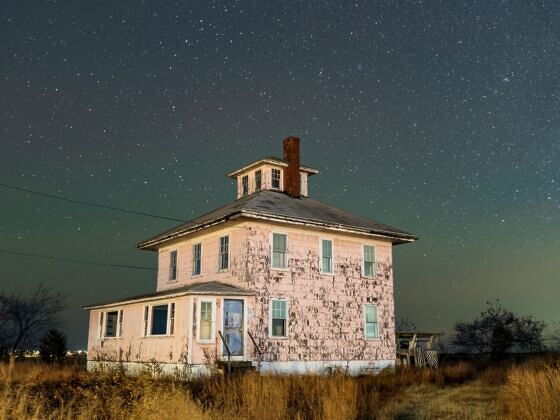

Most summer days, an artist stands on the side of the road between the pavement and the marsh, painting the dilapidated Pink House at sunset. By every architectural metric, the Pink House is ugly. Balancing on the marsh that flanks the mile-long road from Newburyport to Plum Island in Massachusetts, the abandoned house survives, just barely, like a man in the twilight of life. The pink paint peels like dead skin, windows with no panes are a toothless smile, and the cordgrass creeps onto the porch threatening to reclaim the land in the name of nature.

This Beautiful Abandoned House Is a Massachusetts Icon, and It’s in Danger of Being Demolished

According to local legend, it was built as a monument to spite. As part of a couple’s divorce agreement in the 1920s, the wife required the husband to build an exact replica of their family home for her to live in, but she didn’t specify where. He chose the salt marsh, which made it rather inhospitable. Despite the location, it’s said that the ex-husband’s family used it as a summer home until the 1940s, when it was sold and occupied by a series of families.

Photo: Anthony DeSantis

While its real history is lost to time, the house has been abandoned since the early 2000s, seeming to float on the marsh, peeling and crumbling and groaning with no company except the artists standing on the roadsides. To them, and to many who grew up passing it on their way to the beach, the Pink House isn’t an eyesore at all – it’s exquisite. Part of that beauty is its resilience, not only against time and nature, but against the human forces threatening to demolish it.

On the brink of destruction

In 2011, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) purchased the house along with nine acres of sensitive tidal creek and salt marsh habitat. According to Matt Hillman, refuge manager at the Parker River National Wildlife Refuge, the house was intended to serve as seasonal staff housing, but when asbestos and lead paint were discovered, the house’s restoration and habitability were considered economically and operationally infeasible.

Photo: Kelly Page

While many believe caring for the Pink House falls under the USFWS’s responsibility, and aligns with their preservation interests, Hillman says the opposite is actually true. Their official mission is as follows:

To administer a national network of lands and waters for the conservation, management and, where appropriate, restoration of the fish, wildlife and plant resources and their habitats within the United States for the benefit of present and future generations of Americans.

“The long-term care and maintenance of a house located within otherwise intact salt marsh and upland habitat detracts from that mission,” Hillman tells me. “It pulls our limited resources (staff time and funds) away from accomplishing important work to protect threatened and endangered species, restore salt marsh habitat, provide high-quality public programming, and maintain aging critical infrastructure.”

There is one solution that seems simple: Sell the house to a local nonprofit or someone who can devote resources to taking care of it. Well, it’s not that easy. According to Hillman, “federal law stipulates that when lands are protected as part of the national wildlife refuge system, they are meant to be preserved in perpetuity. In this case, because the lands on which the house sits are of high ecological value to the refuge’s mission, only an equal value land exchange is applicable.”

The USFWS insists there are only two solutions: the Pink House must either be torn down, or exchanged for a land parcel of similar value and ecological significance, which contains a salt marsh or upland habitats. They’ve spent the past eight years seeking such a parcel, to no avail.

Photo: Leslie Scott-Lysan

And that’s how we got here. In October 2023, the USFWS proposed tearing down the Pink House and building a wildlife viewing platform in its place. They also opened a 30-day comment period for local residents to voice their opinions on the proposal, and the clock counting down the Pink House’s demise officially started ticking.

Tilting at pink windmills

The threat of demolition seemed to jog people from a happy daydream. It became clear that the Pink House wasn’t rendered on canvas in permanent paint. It could be erased. Roused from this daydream, residents responded to the open comment period with sentimental pleas and valiant calls to arms. Photographers shared their Pink House photos online. Artists’ oil and watercolor depictions now hang in every coffee shop. Every day, it seems, editorials in defense of the Pink House crop up in the local paper.

One group that certainly hasn’t been sleeping on this ever-present threat is the Support the Pink House (STPH) organization. Founded in 2015, the nonprofit is dedicated to finding ways to stave off demolition and preserve the beloved local landmark. According to Kelly Page, who’s on the STPH Board of Directors, the group’s Instagram followers increased by 12 percent in November alone (since the comment period opened), account engagement increased 294 percent, and accounts reached increased by 525 percent. This engagement, she believes, has been driven by the now-urgent interest in saving the house.

“I’m also a photographer,” Page says, “and know firsthand how popular Pink House artwork is both locally and even throughout the region. The Pink House isn’t just a cultural icon, but an economic influence.”

Indeed, Pink House photos regularly prove among the most popular for local photographer Peter Neverette.

“My most popular photos are those of the Pink House,” he says. “Out of towners want something that symbolizes Newburyport, and nothing visually represents the area like the Pink House. Locals buy Pink House photos for similar reasons – because it holds a special place in their lives, or in their childhood memories.”

Photo: Peter Neverette

Unfortunately, no amount of Instagram followers, paintings sold, or nostalgia, matter to the federal government. Which leaves the question, now what?

Anyone in the market for a pink house?

All kinds of questions could be raised right now.

Why can’t the USFWS just accept donations to repair it?

Why can’t nonprofits like STPH simply care for the house with volunteer support?

Why isn’t the Pink House’s historic status enough to save it?

And perhaps most significantly: Why did the USFWS purchase the house in the first place without doing their due diligence on its condition? Surely, as the voluntary stewards of a culturally significant property, they must also assume responsibility for its preservation.

All of these questions, particularly the last one, are valid but ultimately irrelevant. Only one question matters: Will a land exchange happen?

According to Hillman, here’s what it would take: “My sincere hope is that this 30-day public comment process sparks enough interest and publicity that a local landowner approaches the Service with a viable land exchange. Potentially suitable properties include those contiguous (preferred) or within one mile of refuge boundaries and containing salt marsh and/or adjacent upland habitats. Crucially, to comply with federal law, the exchange parcel must also be approximately equal in monetary value to the Pink House parcel, and of higher ecological value.”

The Pink House has been appraised at approximately $500,000. For context, salt marsh acreage usually runs about $1,000 per acre. So if you’ve got 400 acres of salt marsh lying around and you’re in the market for an old pink house, please contact the USFWS.

The fate of a cultural icon

It’s a story so old it’s become cliche: the beloved local landmark struggling to survive against government pragmatism. It’s easy to take sides in these stories. Rooting for the little guy and booing the evil government entity feels like a no brainer. But the story is always more complex than that.

The USFWS must understand that the Pink House is more than an inconvenient hindrance to its mission statement. Indeed, tearing it down would actually damage the organization’s relationship with the local community, complicating its long term mission. Similarly, Pink House supporters must contend with reality. A government entity won’t be moved by mere emotion. There are legitimate upkeep costs and roadblocks associated with the house that only concrete solutions, not picket signs, can solve.

Photo: Kelly Page

If the house is saved, it won’t be through petitions and impassioned pleas. It’ll be thanks to the same creativity the Pink House has been inspiring for a century. It’ll be because someone comes forward with a land parcel exchange, or because devoted residents came up with a constructive, workable alternative.

If the house is demolished, people will have to come to terms with the harsh reality that daydreams don’t last forever. Inspiring sights are often inspiring because they’re fleeting. A house adored for clinging to life against all odds may finally meet a long-expected death. Maybe that’s the Pink House’s story.