A short subway ride from Liberty Square takes me straight into the heart of the Avlabari district, an area of Tbilisi’s old town that houses the modern, glass-domed Presidential Palace; the Holy Trinity Cathedral; and the shabby residential blocks where the Armenian community once lived. I’m here, on the eastern side of the Mtkvari River, head down, staring at my phone, hoping to finally understand the directions to an undistinguished house, below which, a young communist named Iosif Jugashvili is said to have printed propaganda material calling for the removal of Nicholas II, Russia’s last emperor.

Indulge Your Soviet Curiosity in Stalin's Secret Printing House in Tbilisi, Georgia

I heard of Stalin’s secret printing house only a couple of days prior while traveling south on the Georgian Military Road from the Russian border town of Vladikavkaz. Looking for lesser-known attractions that would keep me entertained before moving on toward Azerbaijan, I came across a series of online comments that seemed to provide clear instructions on how to indulge my Soviet curiosity. Hiding below a seemingly anonymous brick house just outside the city center was a century-old machine responsible for heightening the rebellious spirit of the Russian proletarians.

As I walk in circles, a passerby notices my confusion and offers to help. “Stalin?” I ask, making a hand gesture that conveys that I’m looking for something that is located underground. He laughs and points me around the corner. A hammer and sickle painted on a red circle mark the door of what I soon discover used to be the headquarters of the Georgian Communist Party.

Iosif Jugashvili, better known as Joseph Stalin, grew up in Gori, a town located two hours west of the capital of Georgia, and moved to Tiflis at the age of 16 to study at the Orthodox Spiritual Seminary, but his ecclesiastical career was short-lived. In the span of a decade, Stalin’s life shifted dramatically. He entered adolescence with the prospect of becoming a priest and exited an atheist, organizer of factory-worker strikes, bank robber, and clandestine publisher of leaflets, manifestos, and papers meant to convert the whole of the South Caucasus to the new subversive doctrine.

Photo: Angelo Zinna

“Excuse me, is this the printing house?” I ask as I enter the room, interrupting a group of men chatting in front of a heavy red velvet curtain. “Follow the lady, she’s just started,” I hear one of them saying in English before turning back to his comrades. “The lady” is a Russian-speaking member of the party who volunteers to guide the few visitors showing up here. Behind her, a Chinese man and his Georgian translator compose the entirety of the tour group. We exit the building to find ourselves in a lush courtyard in front of a run-down house covered by a wooden roof that seems about to collapse. “Two ladies lived in this house until 1906. They would sit on the porch knitting, day in day out,” explains the guide with a subtle smile. “They had only one job: If they saw someone coming too close, they had to push a button once; they pushed it again to signal a false alarm. If they pushed it three times, it meant it was time to hide!”

Photo: Angelo Zinna

Photo: Angelo Zinna

The bell employed to signal the arrival of the police was connected to a room built 15 meters underground where the 1893 German printing press was located. After obtaining authorization from the landlord, a printing press was smuggled into Tbilisi from Baku, Azerbaijan, then dismantled, lowered beneath the ground piece by piece, and reassembled inside the cellar, which became a printing house in 1903. To access the room, the Bolsheviks had to climb down a well and enter a lateral passage dug up in the wall leading to the secret chamber. Thousands of pamphlets were printed illegally in Russian, Georgian, and Armenian and distributed to spread revolutionary ideas throughout the region.

Photo: Angelo Zinna

Stalin had then abandoned the Seminary and was becoming an important figure in the revolutionary movement, thanks to both his unusual money-raising methods and the large workers’ demonstrations he succeeded in organizing. He was arrested in 1902 and, a few months later, deported to Eastern Siberia to serve a three-year sentence. After a first failed attempt to escape, Stalin managed to return to Tiflis and began working at the printing house in 1904, supported by his allies of the Bolshevik movement.

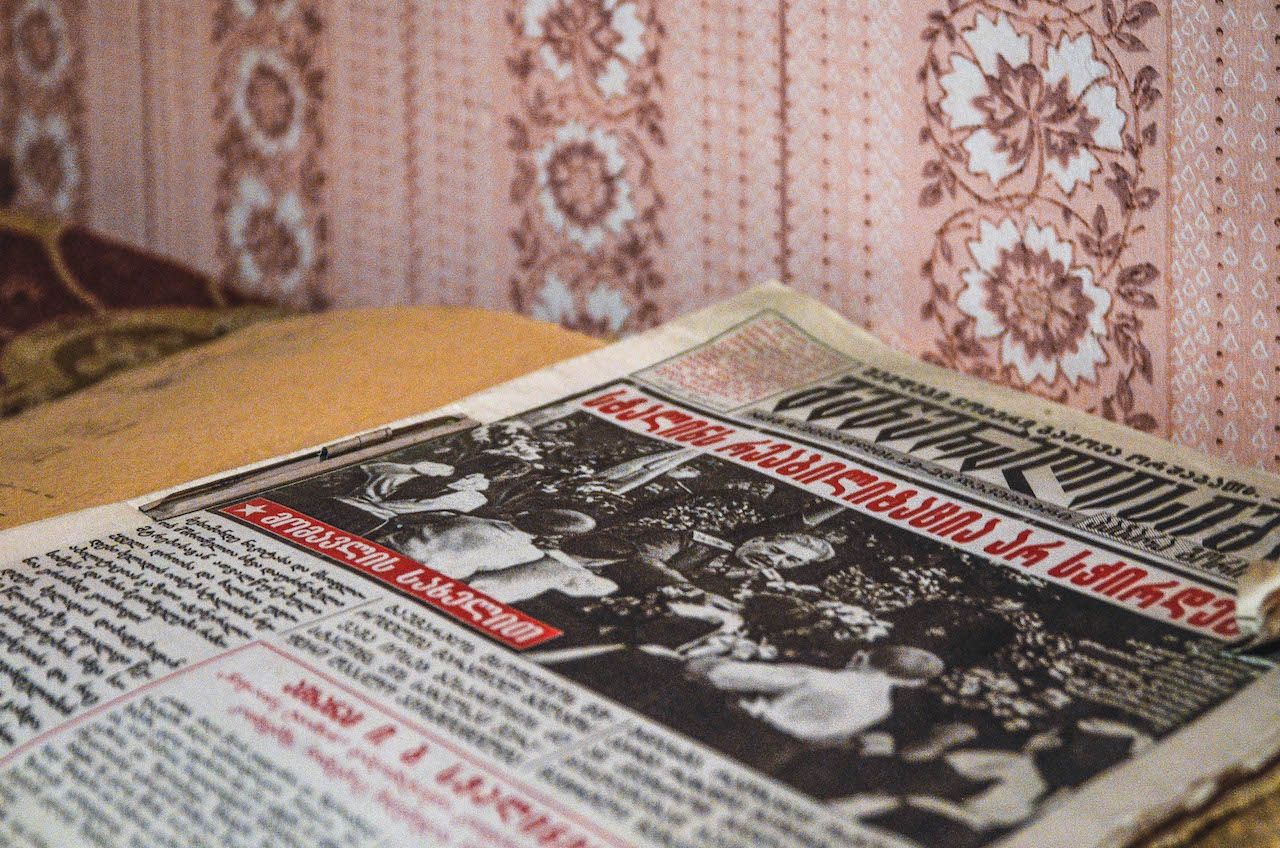

“This is where Iosif used to rest at the end of his shift,” I am told as we visit one of the rooms above ground. In one of the corners of the plain house, there is a single bed protected by a red cord and piles of books are towering up on the window sills. Old newspapers reporting Stalin’s rise to power lie around on shelves and furniture while posters and cutouts hang from the walls, decorating a space that looks more like a shrine than a museum. “We know he has done many bad things,” explains the party representative. “Mistakes were made, we don’t deny it. Politically though, Stalin was a genius. What happened here changed the world. This is history.”

Photo: Angelo Zinna

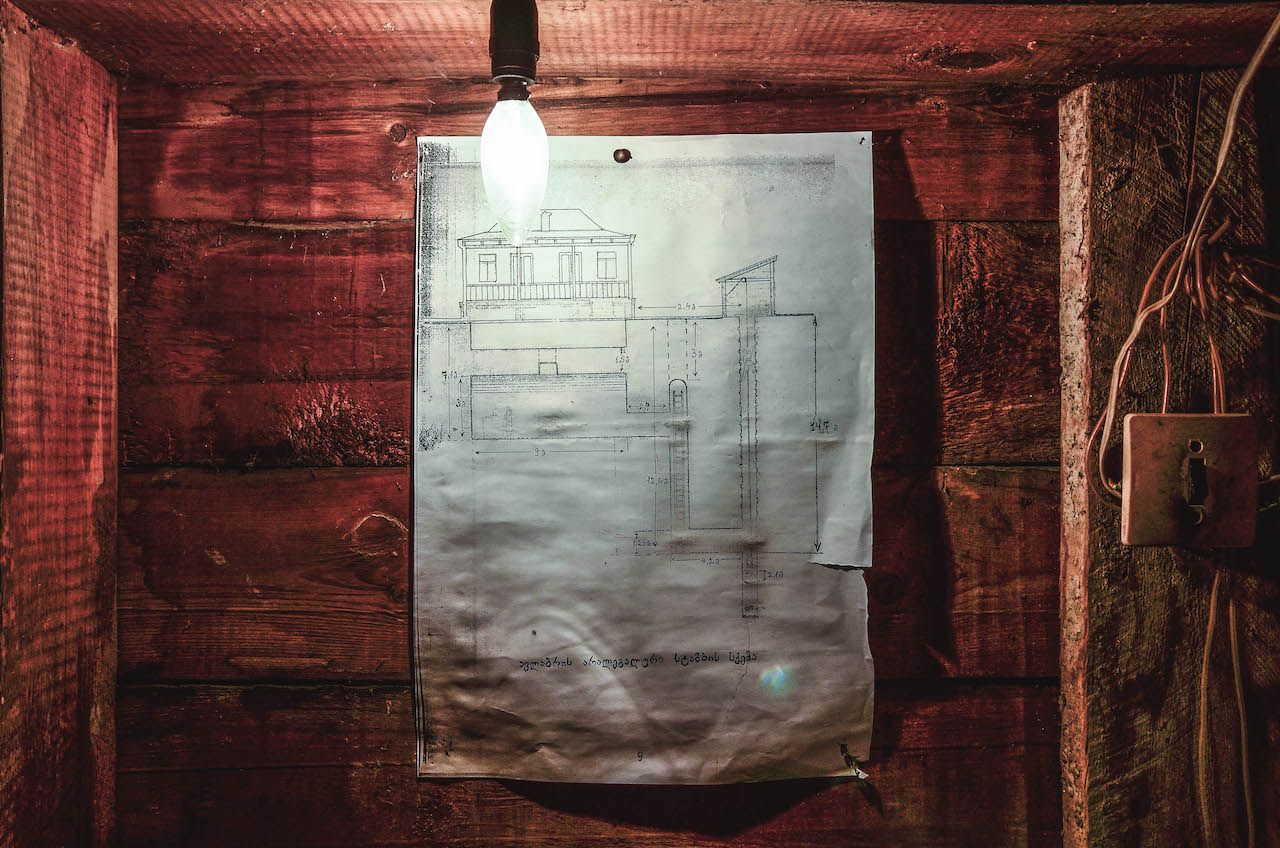

The printing house was discovered by accident in 1906 after the police, suspicious of the constant comings and goings at the house, decided to inspect the building. The printing house, with all its equipment and printed material destroyed, was locked down and left to rot for 31 years until Stalin became the leader of the USSR and decided to give it a second life by transforming the former clandestine workshop into a museum. With the German printing press restored and a metal spiral staircase built as an alternative entrance to the subterranean chamber, Stalin’s printing house became a popular destination for those interested in learning about the origins of the 1917 revolution. Entering the dark, cool room containing the press now covered with a layer of rust is a surreal experience. A map lit by a hanging light bulb shows the original network of tunnels one had to navigate to reach the room and get working on the machine. In the ceiling, the original access point opens into a rectangular black hole.

Photo: Angelo Zinna

With the fall of the Soviet Union began the decline of the museum, which is now under threat of being shut down permanently as part of the de-Sovietization process implemented after the Rose Revolution in 2003. “We are not allowed to call this place a museum. We are banned from doing any promotional activity, sell tickets, or apply for public funding. We’re happy to see visitors coming from words of mouth, but you should know that technically, we’re operating illegally. There’s an active trial going on,” explains Temur Pipia, one of the new leaders of the party. “We’ve been to court once and we will go again. The government wants to tear the building down and give permission to build a hotel. But this is history, we cannot allow it.”

Georgia’s Soviet history is slowly disappearing since the government decided to actively break away from its past and get closer to Europe, but the Georgians are still divided on the topic. In Gori, the six-meter-high statue of the dictator that had been standing in front of the town hall since 1952 was removed with the promise of being substituted with a monument to honor his victims, but Stalin’s birthplace and museum — a famous tourist attraction on which Gori’s economy relies — remains untouched.

Photo: Angelo Zinna

“Come, let me show you our office,” says Pipia noticing my interest. Two large red flags and framed portraits of Lenin and Stalin hang on the wall. An old telephone with a rotary dial sits at the center of the wooden desk, surrounded by newspapers and piles of documents. “This is where we try to keep things from falling apart,” he says laughing.