I put my can of Heady Topper down next to my Glencairn whiskey glass and picked up an axe. My target: a hand-painted board near the WhistlePig whiskey distillery’s guest farmhouse. Central Vermont’s summer cicadas played the soundtrack as I tossed one axe after another, most bouncing off the board. I’ve thrown an axe or two at the sanitized businesses with (I assume) huge insurance policies. This was decidedly not that. This was simply a pre-dinner activity during a WhistlePig farm stay.

For the Best Whiskey-Drinking Experience in the US, Head to Vermont

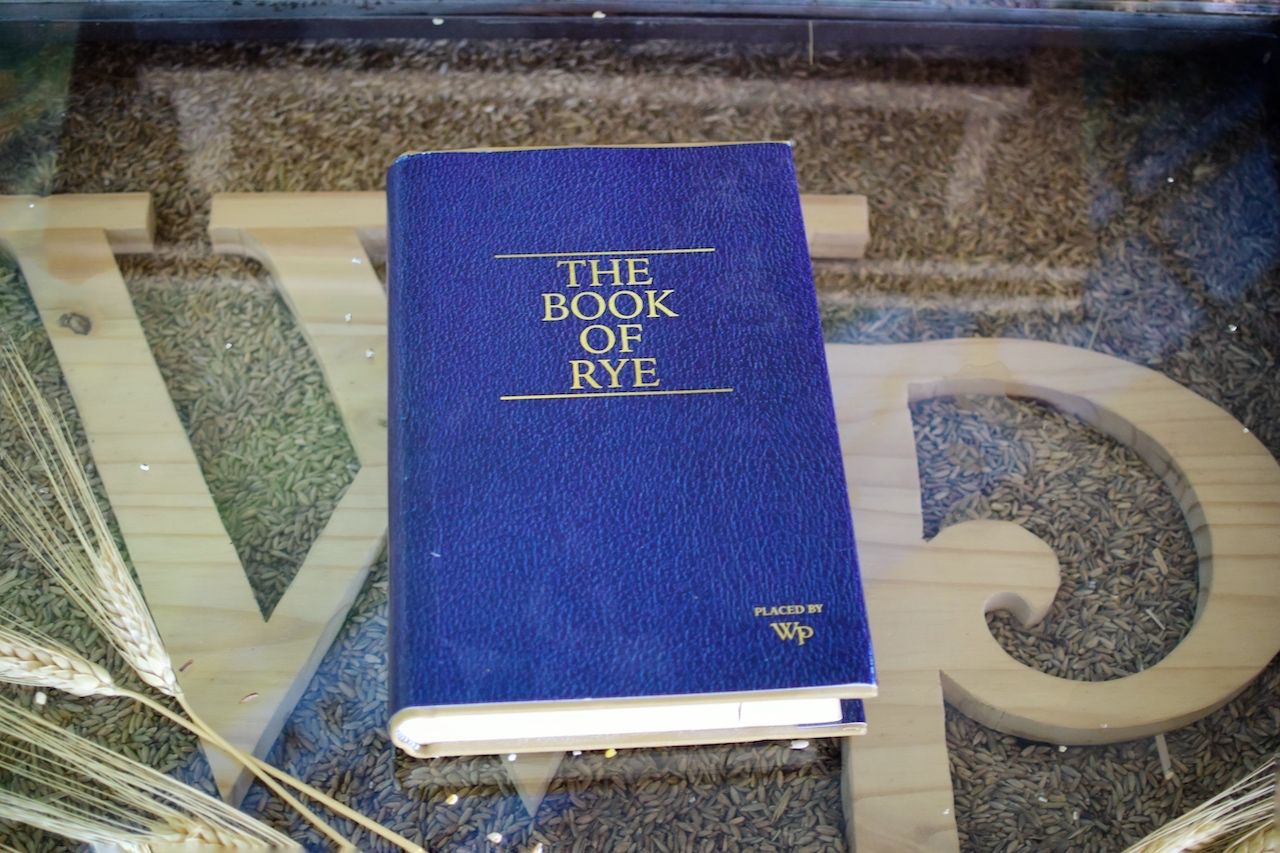

For whiskey enthusiasts, WhistlePig’s farm distillery is what Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory is for Charlie, minus the disappearing children. The private 500-acre farm has an on-site distillery, hand-bottling center, 20 acres of maple trees tapped for syrup, fields of rye, and a five-room guest house complete with a kitchen and upstairs “Rumpus Room” featuring a pool table, full bar, record collection, and arcade games.

But unlike Willy Wonka’s chocolate mansion fun house, you don’t need a golden ticket. To be invited to stay at the farm, you just need to buy a barrel of whiskey — or, more likely, be part of a whiskey group that goes in on a group-picked single barrel.

The barrels for sale come from WhistlePig’s Reserve Barrel Program. The casks are all filled with 10-year-old rye whiskey and range in flavor from aggressive spice to subtle (at least for a cask-strength, single-barrel whiskey). Thanks to third-party distribution laws in the US, anyone interested in buying a barrel has to make the official purchase through a third party with a liquor license, like a liquor store. WhistlePig can help set up the connection between the person buying the barrel and the store. Then comes the fun part. People interested in buying a barrel taste from five or six, which can be done straight from the cask at the farm or from small barrel samples in the person’s hometown. About two months later, 132 bottles with custom labels are delivered to the liquor store for pickup. The cost per barrel depends on the state but ranges from $11,000 to $14,000.

Barrel sales aren’t unique to WhistlePig, but other brands generally restrict the sales to bars, restaurants, and liquor stores. WhistlePig also targets whiskey clubs with members who are collectors or looking for one-of-a-kind bottles. These members also, depending on how many people chip in, are up for spending a big chunk of money for a cult whiskey that they picked out of a crowd of other whiskeys, has a custom label, and can’t be purchased anywhere else.

Behind the initial sticker shock of the price is where the whiskey groups find value. Broken down by bottle, the cost of buying a barrel comes in at an average of less than $100 per bottle (the average shelf price of 10 Year WhistlePig is $81, according to Wine Searcher). Plus there’s the kicker: a multi-day farm stay for five to 10 people who went in on the barrel.

Photo: Nickolaus Hines

If you can’t imagine anyone using both their hard-earned dollars and vacation days on such an experience, the concept isn’t as far-fetched as it sounds. Types of travel that once attracted a niche audience are experiencing a boom, including food-and-drink-focused travel. Particularly whiskey-related travel.

The Kentucky Bourbon Trail hit a record one million visitors for the first time in 2017, and the total who’ve visited in the past five years tops 2.5 million people from every state and 25 countries. A global whiskey market research paper forecasts that for 2019 through 2023, “the growing popularity of whiskey-based tourism is expected to propel the growth of the market during the forecast period.”

WhistlePig’s farm stay and barrel buy program merges this interest in whiskey travel with luxury and customization.

“We’re trying to reach consumers more directly,” says Pete Lynch, WhistlePig’s master blender. “To let them pick their own barrel, do their own bespoke blend, whatever it’s going to be. It’s a harder route to take, but it’s the best way to customize an experience and perfect it.”

As far as whiskey experiences go, WhistlePig is at the apex. Once a group buys a barrel, they pick an available date for their stay. Sometimes it’s groups of 10, other times two groups of five. Lynch describes the availability as somewhat like a doctors office where the farm is booked for the next one-to-three months, but depending on your flexibility, a date could open up within a few weeks due to cancellations and other factors.

Once you’re there, the experience is whatever you want it to be. You set your own itinerary from a list of activities provided by the WhistlePig farm stay team, and you stay in a five-room farmhouse on the property that’s best described as upscale rustic. The group that bought the barrel has the two-story farm house to themselves. The house wouldn’t be out of place in a nice suburb, except that it has a cleaning crew and an on-site chef who cooks using ingredients sourced from local farms. Plus the fact that it’s surrounded by Vermont’s farm-to-glass whiskey distillery.

See the fields of rye and the grist mill or just hang around the stills and barrel room. Go hiking through one of the many trails and take a fly-fishing expedition, or drink cocktails in the tiki-themed sugar shack (where the sap of WhistlePig’s maple trees ends up before being made into a house-brand maple syrup) and sip beer in the Rumpus Room. Whatever you do, there will be whiskey involved. Lots of it. And then when the day is done, there’s a bonfire behind the guest house where there’s more — you guessed it — whiskey.

“Because each itinerary is literally custom built, we take into account who is coming up and what they want to do once they’ve done the barrel tasting or bespoke blend,” says Ida Levick, who helps run WhistlePig’s barrel program and other product launches.

Photo: Nickolaus Hines

The barrel program and farm stays started organically around five years ago, Lynch says. Other spirits brands offer on-site visits for bars, restaurants, and other people in the industry that buy a barrel for a business. When a consumer brought up doing a similar thing without the industry connection (other than the official third party buyer required for legal reasons), WhistlePig found a way to make it happen. It’s continued to grow year after year, attracting whiskey groups who buy a barrel for members, police units who buy one to auction bottles for charity, and luxury clubs looking to add value for people enrolled. The list goes on. The main thing each of the non-industry barrel buyers have in common is a willingness to travel from around the country to reach the small Vermont farm.

“As whiskey grows, so does everything else around whiskey,” Lynch says, citing whiskey societies like The Bourbon Cartel as a category that’s rapidly grown over the past 10 years and shows signs of continued growth. “[Barrel buys and farm stays weren’t] an angle we had until recently because of a lack of a target audience. We thought, ‘This is something we were not tapping into that we should be.’”

In the process of tapping into barrel buying interest, WhistlePig also tapped into natural travel escapism on the Vermont farm. In addition to rye, the farm has a lovable pig named Mortimer Junior and goats. WhistlePig can set up a fly-fishing outing, and while I personally didn’t catch anything, there are far worse ways to pass time than sipping on a flask of WhistlePig while casting into a gentle Vermont creek. It wasn’t all hustle from one activity to the next — there were relatively calm nightly bonfires after dinner (which included a paper menu with the list of about 10 local farms the ingredients were sourced from) and the continuation of the party over games of pool in the Rumpus Room.

“People sometimes just want to do nothing and hang out,” Lynch says. “More often than not, they’ll bring whiskey from their collections, and typically it’s crazy [bottles]. It’s a way for [whiskey group members] to get together.”

Photo: Nickolaus Hines

The WhistlePig brand seamlessly fits into this pick-your-own-adventure style of a private farm stay. WhistlePig started in 2007 and launched in 2010 with a commitment to rye whiskey. The late former Maker’s Mark master distiller Dave Pickerell was involved early on when WhistlePig bought barrels of 10-year-old rye whiskey from a Canadian distillery that intended to use the whiskey for blending. Pickerell’s name gave credibility to the new company.

WhistlePig quickly became a cult favorite and remained one even as the whiskey community turned against brands that sourced distillate from large distilleries. Then, in 2016, founder Raj Bhakta was very publicly forced out of the company by investors over fraud claims and accusations of drunk driving and cannabis use. Bhakta disputed the claims, yet public leadership at the brand shifted. Still, the popularity continued.

Photo: Nickolaus Hines

Today, WhistlePig feels almost like a Silicon Valley startup that’s not afraid to move fast and break things. When the leadership team sees something they want, they go after it. WhistlePig still sources its whiskey from large distilleries to make custom blends (Lynch says not sourcing isn’t on the table), but it also makes a fair portion of its own whiskey now, including for a program it calls “Triple Terroir.” The three all-Vermont parts include farm-grown rye, local water to bring the whiskey down to proof, and barrels made from Vermont oak trees grown on site. The FarmStock bottles, now on the third iteration, use more than 50 percent estate-grown rye.

While there’s more than enough FarmStock (and every other type of WhistlePig) available to drink on the farm, the single barrel purchase is limited to 10-year-old sourced barrels. Each of those barrels is different from the other.

“Over 10 years, everything changes,” says Meghan Ireland, who works on quality assurance and the logistics side of the barrel program. “What makes single barrel so highly valued is that every barrel is legitimately different.”

Photo: Nickolaus Hines

After touring the farm and the distillery the day I arrived, Ireland and Lynch led me and a small group of whiskey writers and photographers to the rickhouse where barrels are stored. Ireland dipped a whiskey thief into a barrel and poured us a sample. The heat of the straight whiskey stayed on my tongue for what felt like hours, though by that point, it could’ve been a culmination of all the tastings I’d done that afternoon.

Looking at the barrels, one thought kept coming back to me: For the right whiskey lover with a desire to stay on a working farm distillery, all this can be yours for the weekend, the memories of which stay fresh for however long it takes to polish off 132 bottles of hand-picked whiskey.