In 1980, after many mishaps and roadblocks, an unlikely restaurant opened in Miami that would help change the face of the city. Called Hy Vong, it was one of Miami’s first Vietnamese restaurants, and it reflected how post-war immigration was changing the culinary face of America. But it was special for another reason: Hy Vong was owned and operated by two women, one of them a single mother who fled Vietnam during the war, and the other, the woman who gave her a home in Miami.

How the Women Behind Hy Vong Helped Miami Fall in Love With Vietnamese Food

In 1975, Kathy Manning welcomed 14 Vietnam War refugees into her home. One of them, Tung Nguyen, quickly established herself in the kitchen — the place she felt safest and most comfortable in her new and often confusing life in America.

Though Tung struggled to adjust, she found a kindred spirit in Kathy. Not only did Kathy praise and admire Tung’s cooking, but as it turned out the women shared many values: Both women desired equality in their relationships and craved independence. Long after all the other refugees had left Manning’s house, Tung remained in Kathy’s home, where she eventually took up permanent residence with her daughter, Lyn. The trio formed an unconventional family unit, and both Tung and Kathy shared in parenting duties for Lyn.

Kathy and Tung were equal partners at Hy Vong, too — often butting heads over how to run the restaurant. Tung was the dedicated, passionate cook who handled all the recipes, and her highly praised dishes drew in a loyal following. Her focus was on making sure the restaurant turned a profit. Meanwhile, Kathy worked the front of the house, keeping her customers satisfied and happy. Together, they kept Hy Vong open for 35 years.

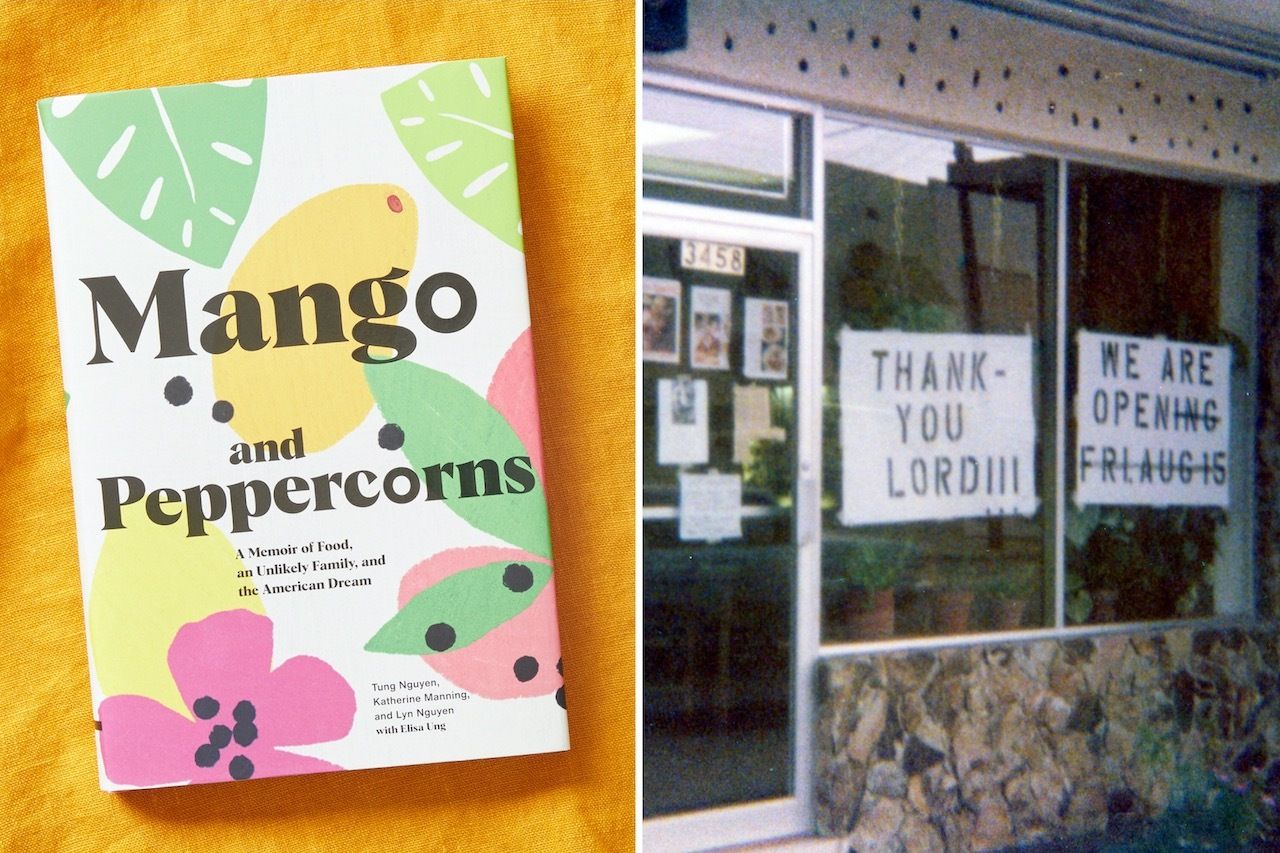

When the restaurant closed in 2015, Tung kept cooking, running pop up Vietnamese feasts in the Miami area, which she still does to this day. Earlier this year, Kathy and Tung, along with input from Lyn, published their memoir Mango and Peppercorns, which reveals how they navigated their sometimes rocky business relationship, co-parenting, and managing one of the most iconic restaurants in Miami.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Photo: Tung Nguyen and Kathy Manning

In the introduction to Mango and Peppercorns, Michelle Berstein writes that she credits Hy Vong with introducing Miami to Vietnamese cuisine and culture. Do you agree that your restaurant helped Miami fall in love with Vietnamese food? What impact did the restaurant have on the city long term from their perspective?

Kathy: We were the first Vietnamese restaurant in the area. Many locals, not knowing the difference, called us Chinese. Most people had not tasted fish sauce, lemongrass, or even ginger. These ingredients were so hard to find that in the beginning we grew our own lemongrass to use in the restaurant.

When we sold spring rolls at the Orange Bowl parade, I kept reducing the price and nobody would buy them because they were too different. Eventually I had to give them away, calling them “Vietnamese hot dogs.”

People liked Hy Vong food not just because it was new, but because it was really good.

Customers would say that Hy Vong food was to die for. Even six years after being closed, we still get phone calls from customers asking for our food. Today, Miami is a hot spot for foodies with a lot of diverse cuisines. We like to think that we helped start that.

Both of you have a deeply rooted sense of independence and a value system that prioritizes equality. How did that value system impact your relationship as friends and business partners?

Kathy: We were both a bit of social misfits who had a strong sense of self. Growing up, I was fat and a tom boy who climbed trees and rode horses bareback. I didn’t fit the typical wife mold that was expected of young girls in my social circles.

When Tung came to the US, she was out of her element. She wanted a husband like her mother and father’s relationship where they loved each other. Initially we became close business partners because we had the same values of hard work, honesty, and quality. We became family because we realized that we could form our own family how we wanted it and we did not need to follow traditional paths. Our independence allowed us to be willing to try new things, like open Hy Vong, and form an untraditional family.

There’s a strong sense throughout the book that Kathy wanted to make people happy and Tung wanted to make a profit at the restaurant, and sometimes those goals were at odds. Looking back, do you feel that ultimately you needed both sides of that coin to make Hy Vong work for as long as it did?

Kathy: Looking back, it worked. We each had our own job that led to Hy Vong’s success. Tung never compromised her food. She used everything and did not waste it. I was the go-between for customers and Tung. I had unconditional love for our customers. Eating together was communion.

Tung: We each had our own job. I loved feeding people. I took care of the kitchen, Kathy took care of the front. We both loved what we did.

The idea of a chosen family that allows each member to be her true, unfiltered self is sprinkled throughout the book. How did that dynamic help Kathy and Tung maintain a partnership in both the restaurant and raising Lyn?

Kathy: We were both independent. Tung had had to learn things on her own from a very young age, and I knew that I didn’t fit the traditional model. And neither of us were willing to compromise who we were in order to fit in. In the early days, when people didn’t eat as much spicy food as they do today, she would still not reduce the spicy level in chicken with lemongrass or spicy ribs because that was how she felt the dishes were best flavored. Tung spoke through her food and was able to express her identity through her cooking. I ran the front like I wanted, and ensured all customers were equal and welcome.

Photo: Hy Vong/Facebook

We were both able to be ourselves and not compromise on who we were. And we were able to find success, happiness and appreciation for who we were. I found purpose from having children and having a restaurant. I felt that I was right where I was supposed to be.

In her section of the book, Lyn writes that from the outside it seems like Kathy and Tung are totally dysfunctional, but at their core, they actually share more similarities than differences: “hard-working, hard-headed, determined.”

Kathy: I was always determined, hard-headed, and a dreamer. If we didn’t have those traits, we wouldn’t have been able to build and run a restaurant for 38 years. Running a restaurant is hard, but you do it because you love it — you love the customers, the joy that food brings, the excitement of introducing new flavors to people. We could have never been successful and ran a restaurant for so long if we got discouraged at every little thing that went wrong. It took us two and a half years to open the restaurant — we had to re-drywall the restaurant twice.

Tung: I had to survive. I had to raise my daughter. I knew that I had to make a better life for Lyn than she could have had in Vietnam. She had so many books and toys. I wanted her to be the best that she could be and to do more than she could have done in Vietnam. I didn’t know how else to give her a better life than to work hard. So I worked hard, every day. I never changed my food or took shortcuts because then that ruins my integrity. I would only serve the best that I could make.

Lyn also writes that the way Tung “communicated with the world” was through her food at Hy Vong. Is that still true, and what exactly is she trying to communicate through the food she shares with others?

Tung: My English is still hard to understand, but now I feel comfortable talking with people. Now I cook for people because I want them to enjoy my food, to be happy, to eat good food. My cooking is my art, and I want people to enjoy my art. That’s still a way that I communicate.

People used to say that, “Tung is in a bad mood today — the spicy ribs will kill you, they are so hot.”

At one point, Kathy makes the simple but resonate point that if you ignore or dismiss the cuisine and culture of immigrant communities in your city, you miss an opportunity for understanding and connection. How does embracing the food of immigrants make you a better citizen of your own community?

Kathy: If you eat in a restaurant like Hy Vong, you get to know the owners, busboys, waitresses. Our customers got to know all our busboys by name. At Hy Vong you got great food but you also get to know the people. One of my busboys came from a poor Colombian family, worked in our restaurant, and was accepted to Columbia University. One of our customers who owned an airline gave him a free ride to school.

Our customers gave us all kinds of help: they built a bench for people to sit on while they waited; they helped fix the bathroom; they gave us a mortgage when a bank would not. Our customers are special. They loved us as much as we loved them.

One evening, we had a new dish, sauteed calamari, and I convinced a customer to try it. He loved it so much that he shared it with the table next to him. The plate of calamari eventually ended up being shared across five tables. When you sat and waited in a small restaurant where food would pass from one table to the next, you couldn’t help but get to know new and different people. And by being open to trying new food, I like to think that they also were open to meeting new people and opening their minds, and maybe even expanding their community.