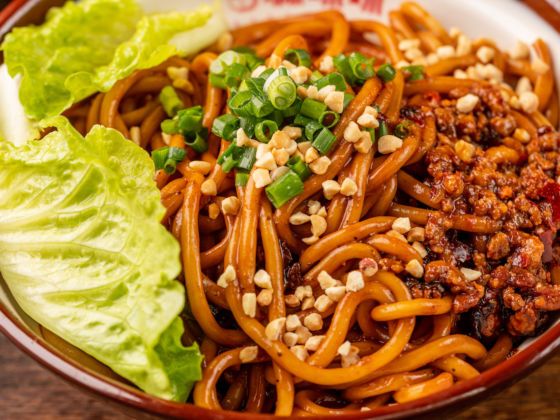

On the morning of April 8, Wuhan, ground zero of the global coronavirus outbreak, quietly reopened after 78 days of lockdown. Breakfast stalls selling hot dry noodles opened, too. Eager customers quickly lined up. Dine-in service was still not allowed. Many eaters just dug into their noodle bowls standing on the curbside.

“I haven’t had it for two months. I’ve missed it a lot,” a woman exclaimed, holding an almost-finished paper cup of hot dry noodles in her hands, in a video posted on social media.