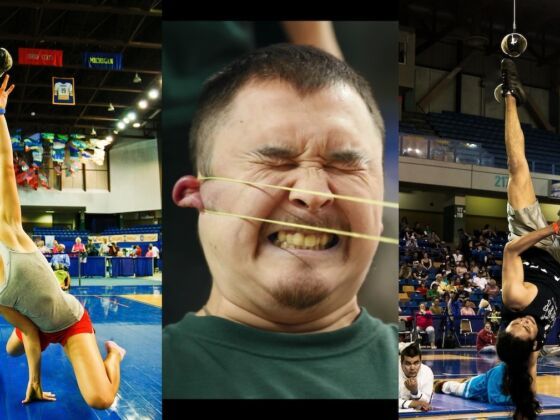

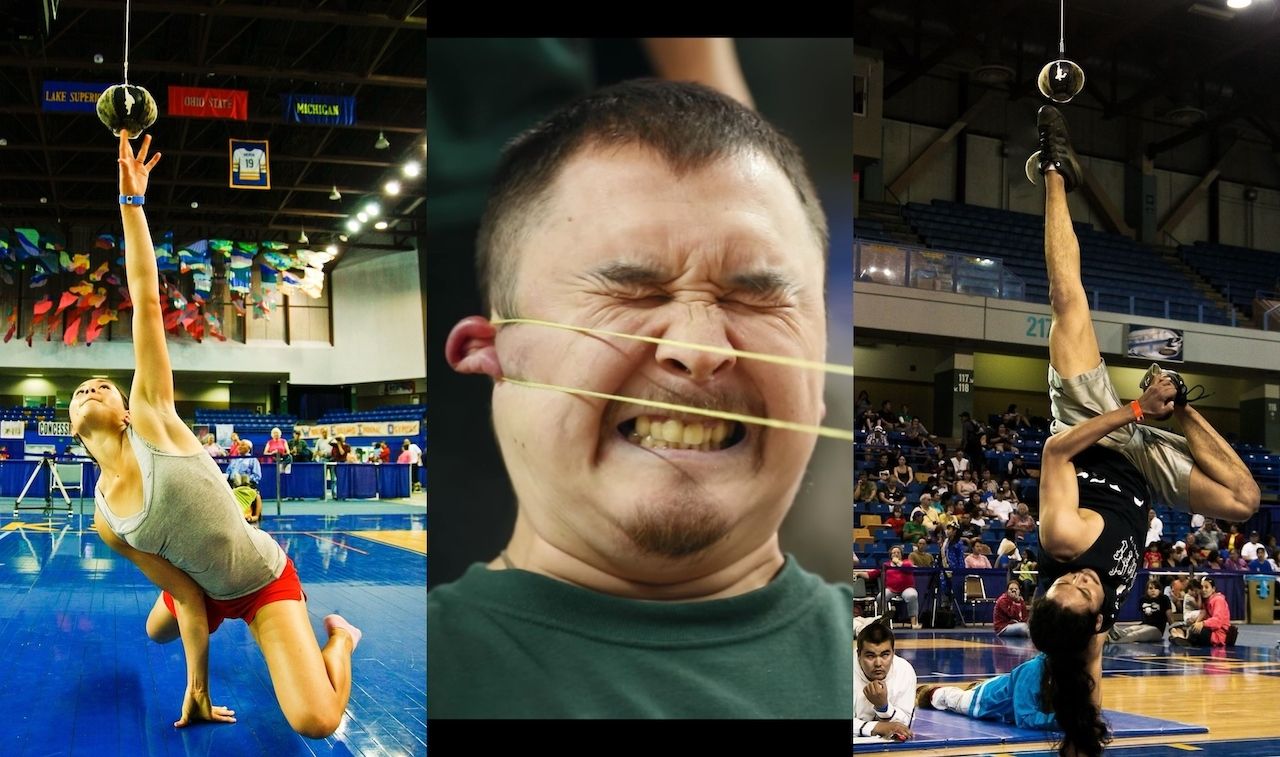

The Olympics are underway, and Alaskans are particularly riveted. No, it’s not because Alaska seceded from the US and entered the Tokyo Olympics as its own country. Since 1961, Alaska has hosted the World Eskimo-Indian Olympics (WEIO) — a four-day event for athletes of Native heritage. The event, which is taking place from July 21 to July 24 this year, draws competitors from all over the state and internationally to compete in games rooted in survival skills and traditional cultural practices. It’s a celebration of the traditional Native culture for the Indigenous communities of the circumpolar region. And unlike the Tokyo Olympics, WEIO is actually allowing crowds this year.

The first WEIO were held in Fairbanks in 1961, as the brainchild of two commercial airline pilots who were flying over some of Alaska’s outlying communities. The pilots, Bill English and Tom Richards Sr., witnessed Indigenous Alaskans performing dances and other activities, like the blanket toss, and thought the rest of the state — namely those living in major cities — could benefit from seeing these traditions up close. Shortly thereafter, the now-defunct Wien Air Alaska hosted the first WEIO, offering to fly athletes from their villages to Fairbanks to compete. Four Eskimo dance groups and two Indian dance groups competed, along with high-kick, blanket toss, and seal skinning athletes. There was also a Miss Eskimo Olympics Queen Contest. The Olympics were so popular that they were held annually, gaining sponsors, producing merchandise, and attracting international media attention.

“To better appreciate the background of these games,” the WEIO website says, “envision yourself in a community village shelter three hundred years ago with the temperature outside at 60 degrees below zero, with everybody in attendance celebrating a successful seal hunt.”

Last year, the WEIO were canceled due to the pandemic — the first cancellation in its history — so this year’s event has a particularly palpable buzz surrounding it. Thousands of spectators regularly gather to watch hundreds of athletes compete in traditional games.

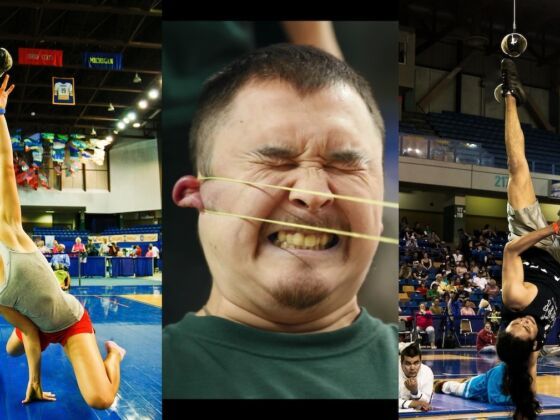

The knuckle hop, for example, requires competitors to hop forward in a push-up position with only their knuckles and toes touching the ground, putting their endurance to the test. In the four-man carry, athletes must carry heavy loads for long periods of time, similar to hauling animal meat home after a hunt. In much the same way, the Indian stick pull mimics grabbing a fish out of the water — two competitors try to grab a greased one-foot-long dowel out of the other’s hand. The Eskimo stick pull requires two athletes to sit on the ground while gripping a stick and pulling, in order to topple their opponent over, testing skills similar to those needed to pull a seal from an ice hole. The ear pull is perhaps the most entertaining, featuring two people with a piece of sinew looped behind their ears who must compete in tug-of-war to rip the sinew from their opponent’s ear.

The WEIO is point of pride for the communities that participate. Amber Applebee, an Athabascan Native, has competed in the competition’s strength events for years, as well as serving as a coach.

Photo: World Eskimo Indian Olympics/Facebook and Greg Lincoln/YouTube

“It’s a tradition amongst [Alaska Natives] to teach,” Applebee told Smithsonian Magazine. “Kids often grow up through this program and see their parents and grandparents competing. We look forward to attending the WEIO because we get to see relatives that we don’t often see. It’s like a big family reunion.”

She added how meaningful it is to pass native traditions onto her children, and how the World Eskimo-Indian Olympics is the gateway for doing that. “It’s really important for me to pass these traditions down from one generation to the next,” she said. “I want my children to know who we are and what our people did, and the WEIO is the best way to do that.”