WE SPENT CHRISTMAS in a hotel in San Francisco. It was called the Edward II, which Dad, the scholar of English Renaissance theatre and history, found both be- and a-musing. We visited the MoMA, walked across the Golden Gate, and hiked the Marin headlands on an unseasonably fine afternoon. Christmas dinner was pasta and a bottle of Barolo in a North Beach restaurant.

Past Tense: Or How I Lost My Dad in a Strange American City

A couple days later, we were in my Mazda Protegé headed south for Los Angeles. I was at the wheel. Which made sense: it was my car, and Dad was used to driving on the left. But it felt all wrong.

When I was growing up in Belfast, the understanding was I would make my own way to school unless it was pouring rain, in which case Dad would drive me. But if I kept him waiting in the car — because I was drying my hair or finishing my French homework — he would just leave.

On board, the rules were clear: I was to be at least minimally agreeable. Once, in a state of outrage about some or other injustice on Dad’s part, I decided to punish him by ignoring him. Before I knew what was happening, he’d pulled over and ordered me to get out — or apologize at once. I apologized.

He taught me to drive when I was seventeen. But the passenger seat was not a place he was accustomed to. His feet would instinctively reach for pedals where there were none. When I took a corner too fast, he would say, “That was appalling! Appalling driving!” Or he would press the back of his head against the head rest, close his eyes and murmur, “Oh God.”

The summer before I went to Oxford, he went away for a month and left me his car. One day, I took the entrance to our driveway at the wrong angle and smashed into the brick gatepost. It seemed like the worst possible thing that could’ve happened. Sobbing, I called my mum in France. “Tell him,” she said. “He won’t be angry.”

She was right — more or less. I reattached the bumper with duct tape and picked Dad up at the airport. He didn’t say much until we got back to the house, where he took a long look at the gatepost. Then he looked at me. “But it doesn’t move,” he said, finally. “I don’t understand how you could hit it, when it doesn’t move.”

I decided we should stop in Santa Barbara for lunch. We’d visited the redwoods and the elephant seals, and had spent the night in a grim motel in Pismo Beach. There didn’t seem to be an exit marked city center or downtown, so I picked one at random. Which might work in a small, concentric European city but is a recipe for disaster in American suburban sprawl.

We found ourselves in a maze of residential streets, like an experiment in house cloning. Finally we spotted a man washing his car. Dad got out and asked for directions.

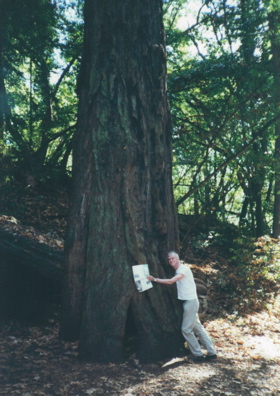

Dad in Big Sur on 27 December, 2000

“Go down here and go right,” Dad said. Which brought us to another street identical to the last.

“You said ‘go right,’” I said.

“At the end of the street.”

“That’s not what you said.”

“Yes it is.”

“No it’s not, Dad.”

“Oh, for God’s sake!”

My dad didn’t belong in California. He liked European cities, long histories and short espressos, mastering the topography with a paper map and a strong pair of shoes. He was six-foot-two and unfailingly self-confident. But California made him seem small, even frail.

“If you don’t like it, you can get out,” I said, pulling over before I’d had a chance to think.

He got out of the car, very calmly, and walked away down the street.

I had no idea what to do. The sensible thing — backing up, apologizing — seemed out of the question. So I drove around the corner. And there my pride evaporated as quickly as it had flared. I did a U-turn and went back. He was gone.

There was nothing to suggest a means of escape — no bus stops, no taxis, not even any other moving vehicles. I drove slowly around the block. Then I returned to the place where he’d got out. Nothing. I pulled over, and proceeded, quietly, to lose it.

My mind constructed worst case scenarios: I’d wait and wait and eventually have to drive back to L.A. on my own. I’d get back, check my phone messages (I didn’t have a mobile), there’d be no word. Maybe he’d turn up late that night, or the next day. Should I call the police? What if he never showed up at all and we became the subject of one of those unsolved mysteries?

I could see no way out. Perhaps I would spend the rest of my life in a white Mazda, waiting for my father.

As I sat there, contemplating the possibility that I had just destroyed one of the most important relationships in my life, I saw Dad come out of a nearby house. He exchanged a few words with an unseen person, then walked quickly and confidently down the drive to my car and got in.

“Dad! I was so worried.”

He seemed surprised. “Were you? I had to use the lavatory, that’s all. A very nice man let me into his house.”

I drove on without a word. What was there to say? Clearly, what had loomed for me as an irreparable rupture in father-daughter relations was, for him, not much more than a well-timed bathroom break. We found the closest thing to a city center that Santa Barbara had to offer, and decided it was not worth the detour. Neither of us mentioned the incident again.