To the rolls of jazz drums and flying camera shots, Michael Keaton race-walks through crowded New York City in his tight underpants in a bizarrely hilarious scene of the dark comedy Birdman.

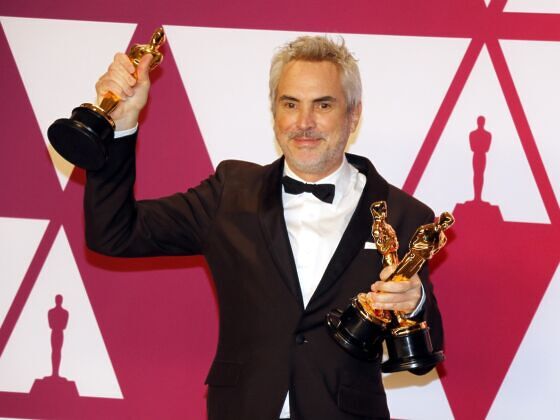

It’s a risky experimental combo. But Mexican director Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu pulled it off on such a scale that his movie won four coveted Oscars Sunday, including the big enchiladas of best director and best movie.