Some tourist attractions in the United States can be pretty expensive — looking at you, Disney World. But if you’ve ever visited a national park, you probably realized that they’re pretty affordable. Some parks are always free, while others charge about $20-35 for week-long pass. An annual pass for admission to every site managed by the National Park Service (NPS) is only $90 per year (or free, if there’s a veteran or fourth-grader in the family).

The National Park Service Just Got $100 Million to Combat Overtourism. But Is It Enough?

That’s because national parks in the United States are primarily funded through federal government appropriations. Each year, Congress allocates funds to the NPS as part of the federal budget process. In 2023, the NPS received approximately $3.3 billion in federal appropriations, which covered operational costs, staffing, conservation efforts, and maintenance. National parks also get revenue from visitor fees and concessions, but they actually generate more revenue for the government than they get back, according to the former NPS director.

National park gift shops are only a very small source of park operating fees. Photo: NPS/Public domain

So when the park service gets a significant grant from a private organization, like the recent donation from the Lilly Endowment, Inc., it’s a big deal. And it’s an especially big deal when that grant is for $100 million — the largest grant in the history of the US National Park Service.

The news came on August 26, with the note that funds would be spread throughout the more than 400 sites managed by the park service. An announcement from the National Parks Foundation (the official fundraising partner of the NPS) announced soonafter that the grant will used in four key priority areas. And three of the four relate to saving the parks from overtourism. The $100 million park grant will go inspiring park stewards of the future, protecting threatened wildlife and ecosystems, improving the visitor experience, and telling a more complete story of America.

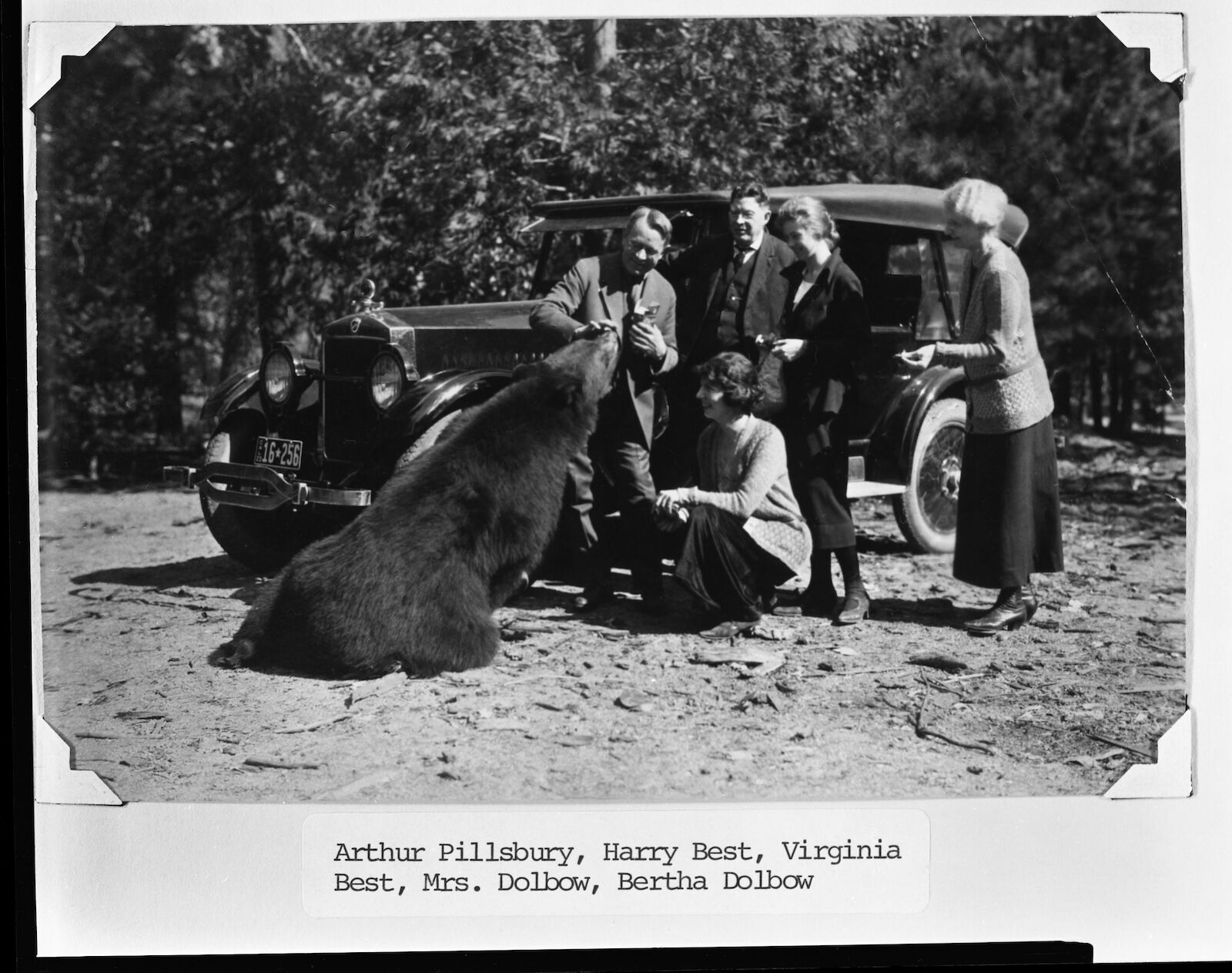

In many ways, visitor behavior has improved at parks in recent times, as seen in this photo from Yosemite, likely circa 1940. The problem now is that there are just so many more guests in national parks today. Photo: NPS/Yosemite National Park Archives

Tourism to national parks has been through the roof in recent years, with parks like Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Great Smoky Mountains on track for one of their highest-attendance years ever. While few people will find fault with encouraging Americans to spend more time outdoors, it’s become clear that many visitors don’t know how to safely and sustainably recreate outside. As a result, parks across the US have seen increases in intentionally and unintentionally stupid and damaging behavior, from visitors scaring wildlife in Wyoming to trespassing on closed trails in Maine to chopping down endangered Joshua trees in California.

All the messaging in the world on how to Leave No Trace, practicing low-impact hiking, and even how to poop outdoors can’t stop damage from overvisitation, it seems. And while it’s nice that the grant funds will mirror the mission of the National Park Service (“The National Park Service preserves unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations,”) anyone who enjoys national parks can and should take a few simple steps to help that $100 million go as far as possible.

Bear bins are for all guests (yes, including you). Knowing how and when to use them can help keep bears alive and wild. Photo: NPS/Public Domain

Part of the grant will be used to “inspire the next generation of park stewards.” It’s important that all children and first-time visitors to national parks learn to love and respect them. But for people who have access to green spaces and parks near their homes, teaching children to respect and love the natural environment before setting foot in a national park can be a great way to make sure they know the basics of Leave No Trace recreation from a young age. That would allow the park service to spend this part of the money on efforts to teach proactive protection — for example, how to leave parks better than you found them — rather than spending money to correct basic behavior people should know from a young age, like not littering.

Without a doubt, the funds spent to “conserve and preserve threatened parks and wildlife” are essential. However, human activity is part of the reason some ecosystems are at risk, from activities like disturbing birds’ nesting sites, walking on fragile protected areas, and introducing microplastics, chemicals, and CO2 into park environments (not to mention the effects of climate change that aren’t localized to a single park). The funds from the $100 million park grant to help wildlife will stretch as far as possible if we as visitors begin to do a better job of respecting wildlife and giving them space to thrive. Fortunately, all it takes is 10 minutes of learning and research to know what to expect at each park before you go. Read the “Plan Your Visit” page available on every national park website, where it highlights the key things guests should know before visiting.

Many species would be extirpated in the US, were it not for their protected habitats in NPS-managed sites. Photo: NPS/Public Domain

Some money will be spent to “ensure a world-class visitor experience.” This could mean expanding park infrastructure to allow for more visitors in a less damaging way. But it’s hard to know if this ultimately be good for the parks. In a perfect world, paving green space to make way for larger parking lots and building multi-lane roads through parks isn’t ideal. But we live in the real world, where impatient tourists will park on hillsides to take photos and spend 30 minutes idling their cars in parking lots to wait for a space.

Additionally, it’s also important to ensure that everyone feels parks are accessible and available to them, as all Americans have an equal ownership over our shared national spaces. So making the visitation process better could be a good thing. Basically, only time will tell if the money spent to “ensure a world-class guest experience” improves parks in the long term, or just allows for the overtourism problem to get even bigger in the future.

Finally, a segment of the $100 million park grant will be used to “tell a more complete story of America,” and is the only allocation not directly related to overtourism. Of course, it is related to the country’s history of forcefully stealing what is now federal land from Indigenous Americans, especially in the American West. I adore our national parks and am so happy they exist, but that doesn’t mean the path to create them was flawless or fair.

It’s unclear what exactly this section of funds will support, but sites in and outside of parks that celebrate the past and current cultures of Indigenous Americans are some of the best offerings in the park system. Highlights include the “Indian Village of the Ahwahnee” in Yosemite National Park, the exhibit on the Native American occupation of Alcatraz Island in Golden Gate National Recreation Area, and touring the Pueblo cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado, among many others.

It would be great to see portions of the $100 million park grant spent on preserving more sites like those, in addition to efforts to involve historic land holders in park management and decision-making, or working to create ways to help Indigenous Americans or people of Native American descent feel more ownership and benefit of park sites. Indigenous-owned nature tours, anyone?

The occupation of Alcatraz Island by the group Indians of All Tribes lasted for nineteen months, from November 20, 1969, to June 11, 1971, and was forcibly ended by the government. Photo: NPS/Stephen Shames/Polaris/Public Domain

National parks are often referred to “America’s best idea,” and Americans are extremely fortunately not just to have so many protected outdoor spaces, but to live in a country where people generally want to protect and preserve them (at least in some capacity). Data so far for 2024 shows that visiting national park sites will continue to be popular. But with just a little extra effort and responsibility, all of us visiting those parks can do a great deal to make the $100 million park grant — and all future funding for national parks — be as beneficial and effective as possible.