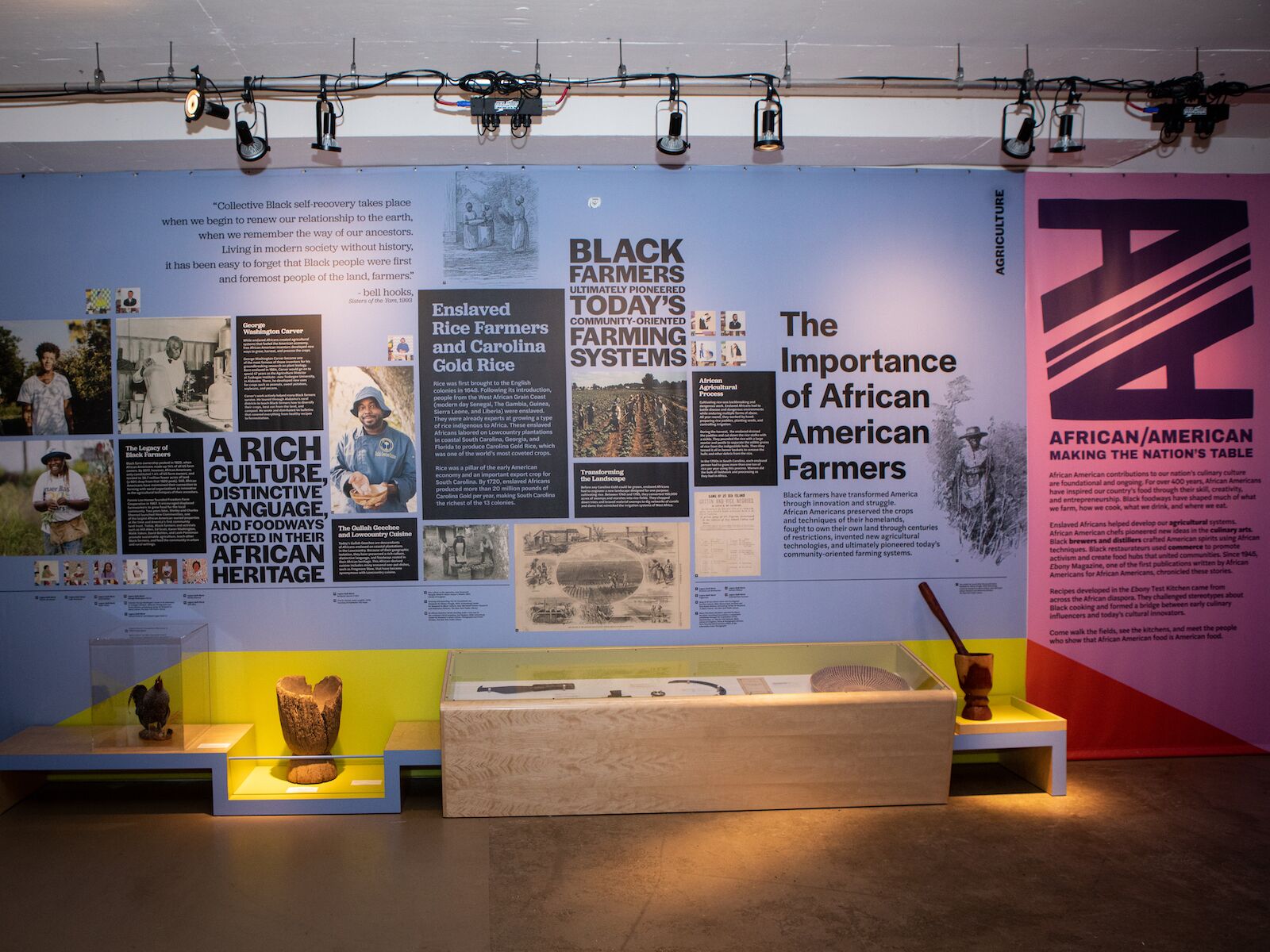

One consistently (and unjustly) overlooked aspect of the cuisine of the United States begins in the Middle Passage, when enslaved people were forced to journey to a new world, carrying within themselves the recipes of their homes. Americans can still taste the ingredients and cooking techniques that enslaved African people brought with them to North America, whether they’re eating barbecue, southern, soul food. A new exhibit inside the The Africa Center at the Museum of Food and Drink in New York City, “African/American: Making the Nation’s Table”, highlights these extraordinary culinary contributions and features Black chefs, farmers, and food and drink producers who played a pivotal part in creating America’s food culture.

This Museum Exhibit Showcases African Americans’ Underappreciated Contributions to American Cuisine

Dr. Jessica B. Harris, known most notably for her book High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America which inspired the 2021 Netflix documentary series of the same name, curated the exhibit. She worked alongside a 30-person advisory committee, including acclaimed chef Pierre Thiam who’s best known for spotlighting West African cuisine at his restaurant Teranga which is also located inside The Africa Center.

Photo: Clay Williams

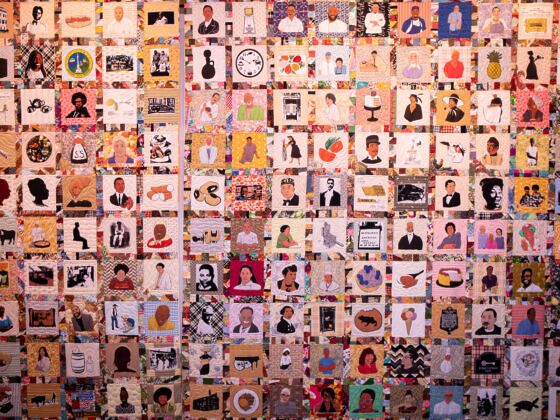

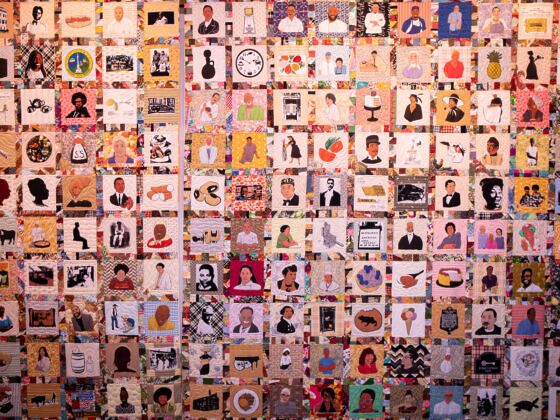

Highlights of the exhibit include the Legacy Quilt, which was illustrated by Adrian Franks and sewn by the quilting collective Harlem Needle Arts. The 14 feet tall and nearly 28 feet wide quilt honors the heroes of African American food culture, from the early days of slavery to the present. You’ll find faces like A’Lelia Walker, daughter of Madam C.J. Walker, who entertained Harlem’s elite with cultural salons and dinner parties during the Harlem Renaissance. You’ll also find present-day faces like Leah Chase who passed in 2019 at age 96, owner She owned the iconic Dooky Chase’s restaurant in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Visitors can also enjoy the Ebony magazine test kitchen, which will take you back in time to the 1970s, where the magazine tested, and eventually printed, recipes popular among African American communities, like stewed chicken and dumplings. The interactive dinner table that’s meant to unlock stories about migration, cultural evolution, and enjoying a meal with loved ones. Enjoy a bite to eat from one of the “shoebox lunches” named for African American train travelers who packed their meals in shoeboxes during the Great Migration, when they were refused service in the train’s dining car.

“African/American: Making the Nation’s Table” is on display at the Africa Center in Harlem through June 19, 2022. Here, Pierre Thiam details his experience working on the exhibit with Harris and the rest of the advisory committee, as they pieced together how to tell the story of African Americans and how their food shaped the United States.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Matador Network: What was your role in the exhibit?

Pierre Thiam: I was on the advisory committee when we started to think about the direction of this exhibit, what it could mean and what it should talk about. It was mainly African Americans — professionals from the diaspora, obviously, Jessica Harris, who was the inspiration behind this vision as part of it and a powerful force in shaping it. In addition to proposing the venue, because my restaurant is also at the Africa Center. So when we were looking for a venue, this was an obvious one that made complete sense.

Why is it important to restore the contributions and legacy of African American recipes and cooking traditions to the history of what we think of as modern American cuisine?

For many reasons, one being that African American contributions are immense, especially when it comes to cuisine. When you look at what’s really, for me and for many others, the most exciting part of American cuisine is actually what Africans brought to this continent. It comes from the ingredients, the food culture, and the recipes.

For ingredients, you could go the whole gamut really – from the beans, black-eyed peas, to the grains. Rice is a big one actually — that’s not talked about enough. People often connect rice to Asia, but the rice that’s been brought and grown in America was done intentionally because they were targeting African communities that had knowledge about growing rice. And there are two large families of rice in the world — the Asian rice and the African rice. So during slavery times, for hundreds of years, there was a focus on bringing captive Africans from regions like Senegambia and Nigeria and Guinea because they knew how to grow rice, and they took them to the Carolinas because that was a similar type of climate. That’s the same technology and method of growing rice that was repeated on both sides of the continent by Africans who were experts in it. Obviously, the Europeans didn’t grow rice, so they had no knowledge about rice.

That’s one important ingredient — it spans in the cuisines of Louisiana, New Orleans, all the way to Brazil, to Mexico even — all that region of North America, that’s the African rice. But there’s so many more. You look at the iconic recipes like gumbo, jambalaya — they’re all West African and African American. And that’s important that we talk about that. Everyone is aware that our contribution was not only meaningful, but it also shaped America in the direction food was taken. Reminding people of our contribution can help put some perspective on what America is really.

Photo: Clay Williams

One main goal of this exhibit seems to be to reclaim forgotten cooking knowledge and traditions brought to America by enslaved people and their descendants. How does educating the exhibit visitors on that overlooked history help give all Americans a complete understanding of our past and the food we eat?

When you enter the exhibition, you will see some artifacts, for instance, the Ebony Magazine Test Kitchen. It was a part of the 70s because of the design of the kitchen. You time travel through the exhibition, which really gets you to be more immersed in the challenges that African Americans were facing, and how they were able to overcome it through food and express it through food. So you have things like the lunch boxes that evoke the great migration, telling you a whole part of the story. But in reality, every time you have food in front of you on a plate, there’s a story that’s being told. And that story, in the case of this exhibition, is amplified throughout.

As you go through the exhibit, one of the amazing pieces is the quilt that you will see of African Americans who have contributed in their own different ways into the fabric of this food culture that is American food culture. And the medium that’s even being used — the quilt, which is also a symbolic technique for storytelling. You look at it, and you travel, all the way from the early African American chefs who had been cooking for even the White House, and the quilt recognizes them.

We don’t celebrate our heroes often, but these were heroes, which also reminds us that we were in the kitchen. We were feeding the wealthy white people, feeding this country. So that’s something that really hits you when you visit the exhibition, and you look at all of these different aspects of it, and it’s showing not only our dynamics of our community and our culture, but it’s showing the beauty of it. And we’re still writing our story. Our history is evolving. That’s another thing that the visitor will take away.

What are some other examples of African American recipes or cooking styles that directly influence the way Americans eat today, and how has that history been erased or co-opted by white chefs, restaurants, or food companies?

One symbolic one is gumbo. Oftentimes you hear gumbo, and you say, “Oh, it’s a Cajun dish,” so it’s kind of taking away from the African element of gumbo — which is the only element of gumbo. There is nothing Cajun about it — It’s an African American dish. When they say Cajun and they want to say it’s Creole, like white and Black people together inspired this dish, but it’s not the case at all. Gumbo is a dish that comes directly from West Africa. You see that dish in many cultures of many countries. Nigeria, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea, Mali — they each have their version of gumbo. Still, it’s the same original core recipe of ingredients like okra and seafood over rice. And you see that none of that, in any Western countries, may have contributed to Cajun culture. There’s no such dish. Gumbo itself is the name for okra in the African language. There’s a dish called jambalaya. It’s similar to jollof. As a matter of fact, if you even go to the Gullah Islands, you will see a dish called red rice. That dish is something we consume in Senegal regularly.

The barbecue tradition is an African American tradition, So that’s something also that is very American — we do it on the Fourth of July, everyone barbecues. That tradition came from the African American community. Many other contributions have been hidden by design because it was their way of explaining how they had to portray us as inferior. If you’re inferior, you cannot have such an immense contribution – so you have to hide that contribution or appropriate it.

What was so appealing about working with Adrian Franks and the quilting collective Harlem Needle Arts. And what did this particular group bring to quilting that was essential to the exhibit?

The group brought the story together. Quilting is storytelling. It gives you perspective by the size, the colors, the vibrancy – it says so many things, and at the same time, it’s celebrating our heroes. I’m saying that humbly because I was even surprised to see myself in the quilt. So that really was quite shocking and moving to see such a representation and the span of 400 years. That was such an original way to do it. Other people would think you would just have a little movie or something, and now we have this really connecting piece because this is a tradition we’ve had for hundreds of years. And it’s visually there; it’s colorful, it’s vibrant, it’s Black joy, it’s Black pride, it’s all of that together. I think that piece really was essential and telling.

Photo: Clay Williams

So you talked a little bit about the Ebony magazine test kitchen. What aspects of working with the Ebony test kitchen were exciting or valuable to you? And what significance does the magazine have on the story of African American food?

That magazine was a symbolic magazine growing up in Senegal. I would look forward to holding it in my hands because it showed beautiful Black people. [Senegal was] colonized just like most of Africa, so at the same time, [people in power] had the same intention of portraying us in an inferior position. And Ebony came in and just presented us as beautiful, happy. It was a celebration of all that in so many aspects, and I wasn’t even speaking English at the time. But I could just spend time reading and looking at the pictures in Ebony and feel joy and pride. And there were recipes too that would come with the magazine. It turns out that those recipes were being developed in this test kitchen. So when we found out that there was a test kitchen that Ebony had somewhere in storage in Detroit that was ready to go in a dumpster somewhere that needed to be recovered and restored, it made sense because that magazine was an essential read for African American culture during those times of trouble. It played a role just like all the other cultural elements played a role, like jazz music, in keeping us centered in this heritage that we are passing on to different generations. You know how influential media is. So often, the media portrays us in such a terrible light, which was certainly the case for North America. And Ebony was the other voice to say, that’s not true — you’re lying. We’re not ugly. We’re beautiful. This is us.

And Ebony was introducing the reader to African American life, which was a life to be desired. There were great entertainers here, successful doctors — there were all kinds of profiles showing African Americans in their splendor. And the food was also a big thing too, bringing recipes every month. That food is supposed to nurture the community. It’s more than just putting nutrition into your body. It’s nurturing your community and the food that we serve into our homes, food that’s been passed by our mothers from their grandmothers and their grandmothers, and so on. And you go all the way back to Africa, as I mentioned, the food is coming through the Middle Passage. So this is food that really carries a message. That’s food that, when you enjoy it, you’re also looking at how our people have not only been able to domesticate these ingredients and create some sort of alchemy, taking raw ingredients and turning it into this delicious gumbo. Hundreds of years later, we are still eating it. It’s a kind of time traveling by just having a quick lunch of gumbo or jambalaya.

What do you hope people leave with once they finish the exhibit? What new knowledge or perspectives is essential that guests come away with?

First of all, I hope people leave and become somewhat ambassadors of this message that we are telling America and the world in their own ways because people each have their own way of spreading messages. Just make sure that this conversation continues. It could be continuing on your table. It could be a way of inspiring the way you’re eating – it could be more intentional. I also hope it could help people realize the need to act upon not only supporting this food culture but giving credit to our ancestors for bringing it here. This is a food culture that’s so resilient – having transcended hundreds of years of the most horrible hardship, and yet we are still serving it in such a beautiful and delicious way. So this is a food culture that is a testimony of what our African American culture is – a strong, beautiful, resilient, joyful people and culture. And this is what we should all aim to be. We are a model for this America. You know, this is what America should strive to be. So, after seeing the exhibit, that work should be inspiring us.

And we should also definitely be more inclined to support Black businesses, particularly Black food businesses. The ugly food system that got us in this situation we are in today – when we talk about climate change, when we talk about chronic diseases that we are facing, when we talk about the food deserts and the poison that’s being fed into our communities; Black businesses are the answer to that by bringing our culture and we need to support them for them to thrive and to keep them growing and serving our community the right food. We’re here to nurture our communities and heal us from our trauma.