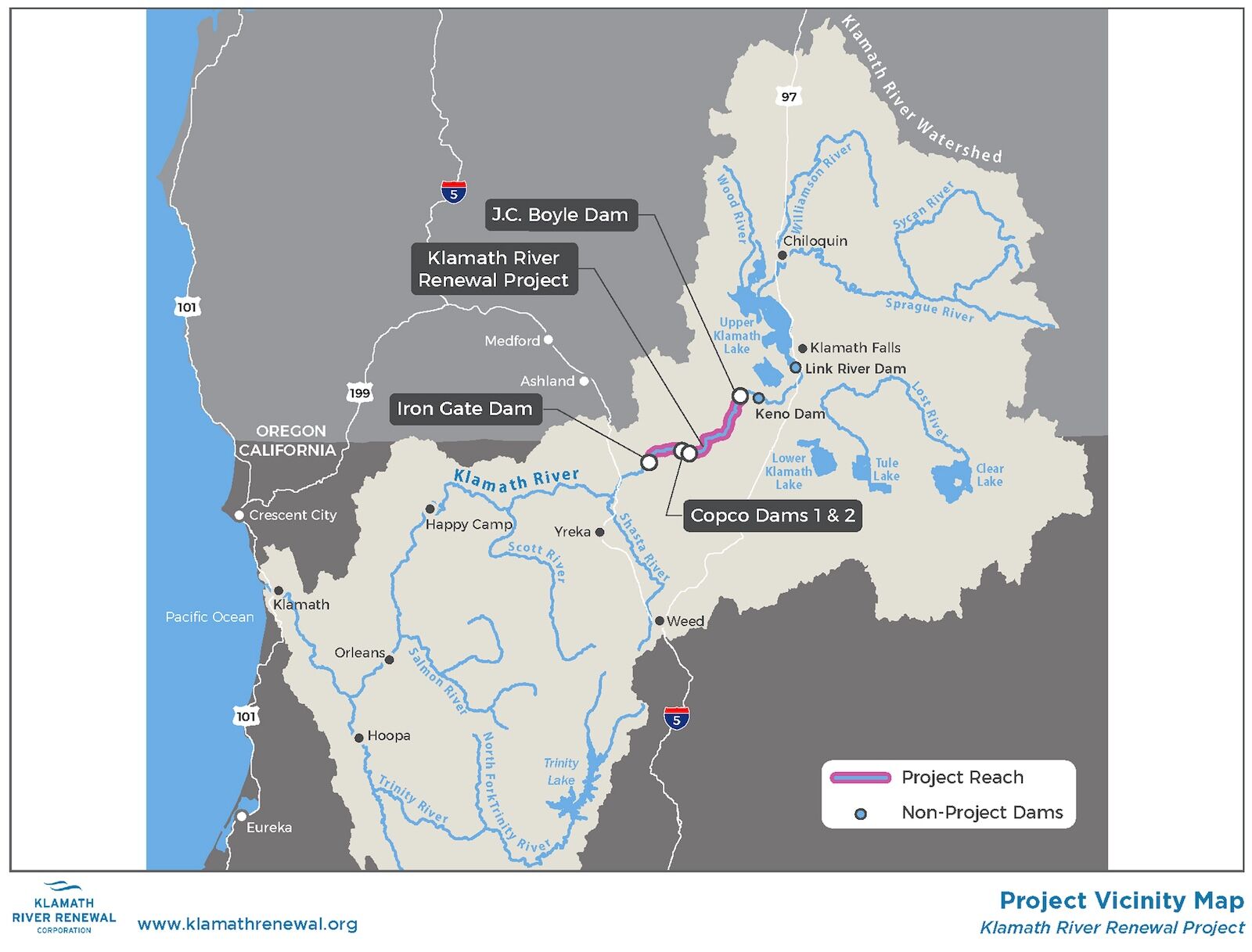

The Klamath River traverses 257 miles from Klamath Lake in Oregon to its mouth in California’s Redwood Coast. The salmon habitat the river supports, however, crosses more than 420 miles through the Klamath’s tributaries, historically one of the most significant salmon runs in the western United States and a primary source of food for the Yurok people for centuries. Throughout the first half of the 20th century, and culminating in the 1960s, a series of hydropower dams were erected along the river, cutting off the salmon runs and devastating the traditions and livelihood of the Indigenous peoples who had depended on the salmon for so long. Now, in a striking reversal of the trend from a century ago, the dams on the Klamath are gone – and for the first time in 100 years, the salmon can retreat to the breeding grounds that have given life to the Pacific Northwest since before humankind first entered the region some 10,000 years ago.

Removing Dams From the Klamath River Is the Latest Win for Salmon - and Momentum Is Growing

What’s more, the Klamath is hardly alone. Similar efforts are underway from the Snake River in Idaho to the Penobscot River in Maine, with one striking factor in common: Though dam removal efforts are complex, they’ve proven in many cases to be less controversial than the erection of the dams in the first place. Rather, few conservation-related efforts have proven more effective at uniting Indigenous peoples with politicians, business leaders, and outdoor recreationists across the political aisle and the broad spectrum of activities taking place on the water. Travelers have an important role in dam removal efforts, too – and it all comes down to where the money’s coming from. Nearly all major dammed rivers in the United States host commercial rafting and fishing outfitters, with both permitted and unpermitted stretches of water open to use for private parties as well. By supporting the outfitters running the rivers, obtaining a rafting or camping permit, or buying a fishing license, those visiting the river are casting their support for the long-term health of the ecosystem they’re visiting.

This goes to show that there’s never been a better time to plan a river trip – but before heading out, it’s important to have a general understanding of what’s happening and why it’s so important.

Why is this dam removal happening, and why is it important?

Photo courtesy Klamath River Renewal Project

The decision to remove a dam on a major river like the Klamath is often multifaceted, involving careful consideration of environmental, economic, and cultural factors. Not least is that these dams generate hydroelectric power, which is then sent into the grid and used to power homes, businesses, and the economy at large. Removing a dam means removing its power generation output, which then must be offset somewhere else (the federal government just announced an increase in acreage available for solar projects on public lands, as one potential solution).

Environmental concerns, such as habitat destruction and fish migration disruption, often drive dam removal efforts. Restoring fish populations – primarily salmon, in the case of the Klamath – can benefit commercial and recreational fishing industries, while improving water quality can positively impact agriculture and tourism. Cultural considerations, particularly for Native American tribes, play a significant role as dam removal can restore ancestral lands and protect cultural heritage.

“I think in September, we may have some Chinook salmon and steelhead moseying upstream and checking things out for the first time in over 60 years,” Bob Pagliuco, NOAA marine habitat resource specialist, said in an article released by NOAA. “Based on what I’ve seen and what I know these fish can do, I think they will start occupying these habitats immediately. There won’t be any great numbers at first, but within several generations—10 to 15 years—new populations will be established.”

The removal of the dams on the Klamath River is the culmination of years – decades, even – of effort on the part of Native tribes, environmental activists, fishermen, and politicians. There has been a growing public awareness of the negative impacts of dams and a shift towards more sustainable and environmentally friendly practices in recent decades, thanks largely to efforts from Indigenous communities and non-profit advocacy groups. The removal of the Klamath River dams is a significant milestone in this movement, as it is one of the largest dam removal projects in US history. It is expected to serve as a model for other river restoration efforts across the country.

What rivers can I visit to support these conservation efforts?

Photo: CSNafzger /Shutterstock

Traveling for a river trip to make a positive impact is one of the most effective ways the general public can support these efforts while learning about the surrounding ecosystem – and having a heck of time while doing it. A few rivers (and outfitters that run them) are:

Snake and Salmon Rivers: Located in the Pacific Northwest, the Snake and Salmon Rivers, particularly the Snake, have been a focal point for dam removal discussion. OARS operates many trips annually on each (be sure to include the stunningly beautiful Hell’s Canyon in any trip you take).

Penobscot River: This river in Maine has seen a series of dam removals in recent years, aimed at improving fish passage and restoring the river’s ecosystem. The Penobscot River Restoration Trust has been instrumental in these efforts. Northern Outdoors runs frequent trips down the river.

Elwha River: In Washington state, the Elwha River has experienced one of the largest dam removal projects in US history. Both the Elwha Dam and the Glines Canyon Dam were removed, resulting in significant improvements to the river’s health and the return of salmon populations. Check with Olympic Peninsula, the local destination marketing organization, for outfitters running the river before you visit.

American River: This river in California has been the subject of dam removal proposals, particularly in the context of restoring salmon habitat and improving water quality. However, these efforts have faced challenges due to the complex issues surrounding water rights and hydroelectric power generation. OARS runs the American, as do several local rafting outfitters.

Traveling with outfitters like OARS, which contributes proceeds to conservation efforts on the rivers it runs, is essential. If traveling with a group of friends on a private expedition, be sure to research any permits you’ll need to float or camp in the area. If you can’t visit in person, several non-profit groups also support river restoration across the United States, including American Rivers and the Western Rivers Conservancy.