When a plane touches down on a runway and you see a new place with fresh eyes, it’s easy to feel — even for just a moment — like an explorer venturing to a blank space on a map. The first travelers weren’t vacationers booking scuba tours but explorers intent on demystifying what was unknown to their own part of the world. While much of the world is pretty well mapped these days, it’s easier than ever to follow in the footsteps of those original pioneers with the help of our new series, Modern Trailblazing.

Channel Your Inner Pioneer With This Lewis and Clark-Inspired Road Trip

Whether it’s hitchhiking, taking an epic train journey, or road-tripping with a friend across Route 66, journeying through the American West has always been a romantic prospect for travelers the world over. Discovering new stretches of the Colorado River and naming mountain peaks might be out of the question in 2020, but that doesn’t mean you can’t relive the journey of the two men who drew the map in the first place: Lewis and Clark.

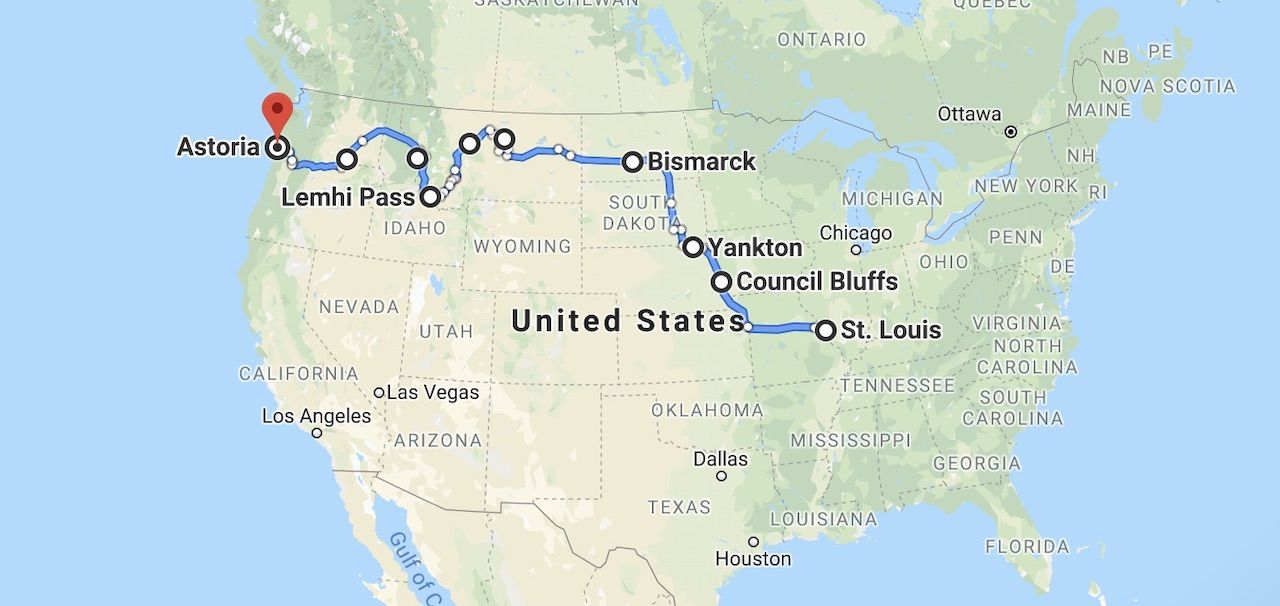

Probably because of our elementary school curriculums, Lewis and Clark are among the first names that come to mind when we think of American adventurers. Their journey began in 1804 when president Thomas Jefferson tasked Meriwether Lewis with exploring the lands acquired in the Louisiana Purchase, west of the Mississippi River. Beginning in St. Louis and ending near present-day Astoria, Oregon, in 1805, the trip covered 8,000 miles and resulted in a wealth of geographic, social, and ecological information about previously uncharted stretches of the continent. The expedition doesn’t capture the imagination because of its scientific learnings, however, but because it’s the first documented American road trip into the West.

Now, the roads are paved, rivers easily crossed, and your chances of contracting smallpox mid-journey slim. Here’s how to follow Lewis and Clark’s road — a little more comfortably — through the West.

St. Charles, Missouri, to Yankton, South Dakota

Photo: Google Maps

The journey officially began in May in St. Charles, Missouri, about 30 minutes outside St. Louis, where Lewis joined up with William Clark and the 43-member “Corps of Volunteers.” From St. Charles, the company headed up the Missouri River in three boats, battling heat, insects, and strong currents through lands inhabited by Native Americans. They bartered with the tribes and presented them with peace offerings but also informed them that their lands now belonged to the United States (who would provide them with military protection). In Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Yankton, South Dakota, the expedition held peaceful councils with the Odo and Sioux tribes respectively.

Photo: Rob Neville Photos/Shutterstock

It might be more practical to begin your road trip in St. Louis, but you should still make a pit stop in St. Charles, even if only for a few hours. The city of 70,000 people, where the Lewis and Clark expedition began in 1804, was the first permanent European settlement on the Missouri River. Any visit to St. Charles should include its Historic District, whose buildings date back to the early 1800s. St. Charles is no St. Louis, and you probably wouldn’t spend a whole week here, but don’t leave without checking out the Lewis and Clark Boat House and Museum, or the memorial dedicated to the two explorers on the west bank frontage where their campsite used to be.

Of course, the Lewis and Clark expedition used keelboats and canoes as their primary means of transportation, but you’ll be forgiven for taking a car instead. Unlike the two explorers, you have the luxury of resting and fueling up at major cities after departing from St. Charles. You’ll pass right through Columbia and Kansas City on your way west along I-70, as you make your way to Council Bluffs, the former site of Lewis and Clark’s meeting with the Odo Tribe. There, they established a campsite now known as Fort Atkinson — the first US military post west of the Missouri River, and a symbol of the earliest friendly formal contact with Native Americans. Later serving as the first school and library in Nebraska, the fort’s original structures still remain and can be visited.

As you continue north to Yankton, South Dakota, where the expedition treated with the Yankton Sioux, make sure to pitstop at the Ionia Volcano on the banks of the Missouri River. You probably weren’t expecting to come across a volcano in Nebraska, but located right off Rt. 12 near Newcastle, this “volcano” is one of the more unique geological features on your trip — even if it isn’t exactly Mt. Hekla. The expedition encountered the Volcano on August 24, 1804, and Clark noted that the 190-foot-high bluff appeared to be on fire, emitting smoke and bearing a coal-like appearance. Although the sporadic eruptions have since been proven to be caused by the high temperatures of the damp shale rock, and not actual volcanic activity, it’s still called a “volcano” and considered sacred by the local Ponca Tribe.

Photo: Trina Barnes/Shutterstock

Continue north through South Dakota at your leisure, visiting the Cheyenne River Reservation and Standing Rock Indian Reservation along the way. These sites will give you a greater appreciation for a culture that has been in the region since long before Lewis and Clark’s journey. At the Cheyenne Reservation, check out the Timber Lake and Area Museum, containing items from the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. At Standing Rock, you can take a much-needed break from the road and go boating and fishing on Lake Oahe. And if you’ve been longing for some urban fun after spending dozens of hours driving through seemingly empty country, Bismark, North Dakota, is just a few hours north of the reservations and the perfect place to refuel for the next leg of your journey.

Washburn, North Dakota, to Great Falls, Montana

After a hostile encounter with the Teton Sioux, Lewis and Clark came upon Mandan and Minitari natives near present-day Washburn, North Dakota. They set up a camp for the winter along the Missouri River called Fort Mandan and spent the next five months there hunting, making canoes, and refreshing their resources. This is also where they met Sacagawea, the Shoshone teenager who famously joined their expedition, along with her husband, Toussaint Charbonneau.

While the story of Sacagawea we’re told as children glazes over the tragic parts of her life (she was captured and sold to the French trapper to at around age 12 and died shortly after the expedition) she is rightfully revered for helping Lewis and Clark immensely with both navigation and communication. Before crossing through Montana, some of the crew was sent back to St. Louis with valuable maps, geological samples, and other scientific information. The rest continued along the Missouri River, stopping near Great Falls, Montana, to abandon Lewis’s leaky boat.

Photo: Joseph Sohm/Shutterstock

Under an hour from Bismarck is the fort where Lewis and Clark passed the winter of 1804-05. Thankfully you don’t have to spend all winter at Fort Mandan, but you should absolutely set aside a few hours to visit the Lewis & Clark Interpretive Center, which is now housed there. Exhibits and hundreds of period artifacts will paint a clearer picture for you of the legendary explorers’ road and the tribulations they faced.

Photo: Traveller70/Shutterstock

Not too far from Fort Mandan, you can visit the place where Lewis and Clark traded with the Mandan and Hidatsa tribes. Near the confluence of the Knife and Missouri Rivers, the Knife River Indian Villages are still standing in the form of earthlodge dwellings, cache pits, and travois trails. This is where Sacagawea was living at the time she met Lewis and Clark and joined their expedition, making these villages one of the most pivotal sites on their trip.

From there, head west through Montana until you reach the White Cliffs, a dramatic geological area inside the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument. The cliffs are formed of white sandstone, rising about 300 feet, and assume an almost architectural quality. The expedition passed through the cliffs on May 31, 1805, and inspired Lewis to write extensively and romantically about them.

Photo: vagabond54/Shutterstock

About three hours southwest of the White Cliffs, make a pit stop in Great Falls. Hopefully by this point your car is faring better than Lewis’s boat, and you’ll be able to stop and appreciate the series of five waterfalls just outside town. Great Falls is also home to the C.M. Russell Museum — a monument to the artist famous for his images of the American West.

Through the Continental Divide

One of the trip’s most arduous portions was the crossing of the Continental Divide. With Sacagawea’s assistance acquiring horses from the local Shoshone tribe, the expedition navigated Idaho’s Lemhi Pass through the Beaverhead Mountains, over 7,000 feet above sea level. Once safely through the pass, they took the treacherous Lolo Trail through the Bitterroot Mountain Range. Struggling with inclement weather, exhaustion, frostbite, and hunger, this was said to be the most difficult leg of the journey. Much needed respite was found along the banks of the Clearwater River, where the Nez Perce tribe fed and cared for the travelers before sending them on their way.

Photo: Philip Bird LRPS CPAGB/Shutterstock

It’s just under a five-hour drive from Great Falls to the Lemhi Pass, but at least you won’t be contending with frostbite and starvation. Just before crossing into Idaho, check out Beaverhead Rock, located right off highway 41. The Shoshone people named the rock for its resemblance to a beaver, and upon seeing it on the expedition, Sacagawea knew she was near the home of her relatives.

Crossing the border from Montana to Idaho means crossing the Lemhi Pass, as Lewis and Clark once did. Sitting right on the Continental Divide and spanning two miles across the border, the pass is surrounded by the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest and the Salmon-Challis National Forest, with stunning views of the trees and mountains. Accessible via Lemhi Pass Road in Montana and the Lewis and Clark Highway in Idaho, the pass consists of a single dirt track, making it easy to imagine the expedition of explorers that once rambled there.

The drive following the pass might be the most scenic of your entire journey. Rt. 93 winds north along the edge of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, known for its snow-capped mountains, rugged forests, and abundance of elk and bighorn sheep (so keep an eye out for elk crossings).

Photo: Joseph Sohm/Shutterstock

The modern-day Lolo Trail extends from Weippe Prairie to the Lolo Pass along the Idaho mountains. The Lolo Motorway is the best way to take the modern-day trail without actually loading up a packhorse. It might be a highway now, but that doesn’t mean the journey is smooth. The road through the mountains is single-lane, bumpy, narrow, and twists around steep ridges. It’s perfectly safe as long as you’re paying attention, but it will give you a semblance of an idea of the hardships Lewis and Clark faced during their passage.

Photo: Robert Travis/Shutterstock

Before embarking on the road, stop at the Lolo Pass Visitor Center on the Montana-Idaho border where you can learn more about Lewis and Clark’s journey through the region, and even take a short interpretive walking trail. Also be sure to check out Packer Meadow in the Clearwater National Forest just east of the visitor center, where hiking trails wind through open glades and along Pack Creek.

Photo: Danita Delmont/Shutterstock

Emerging from the mountainous trail, you’ll be a mere three-hour drive from Kennewick, WA. The ideal place to rest before the final leg of your journey, Kennewick is home to the East Benton County Historical Museum, which highlights the experience of the pioneers who followed in Lewis and Clark’s footsteps. Just north of the city is the Sacagawea Heritage Trail, a scenic loop along the Columbia River through Richland, Kennewick, and Pasco, commemorating the expedition that once passed through there.

Astoria, Oregon

In November of 1805, the expedition finally arrived at the Pacific Ocean after sailing up the Snake and Columbia Rivers in dugout canoes. By Christmas they had constructed Fort Clatsop near present-day Astoria, Oregon, where they spent the winter battling flu-like symptoms, contending with harsh rain, and trying to recover before spring. By March they left Fort Clatsop behind and began the return journey home.

You probably won’t be paddling west across the Columbia River in canoes like the expedition, but on the final leg of your trip, you’ll find yourself at the river’s mouth in Astoria, Oregon. Fittingly, the Pacific Ocean will mark the end of your journey, just as it did for Lewis and Clark.

Photo: Lara J/Shutterstock

Check out Hat Rock State Park, just south of Kennewick. A 70-foot high formation of exposed basalt, Hat Rock was noticed by Clark from his canoe. He remarked that it looked like a hat resting upon the landscape and later included it his notes, in a list of landmarks used to mark distances. Not too far off Highway 730 near Umatilla, Hat Rock is an easy stop and an interesting piece of geography. There are also boating, hiking, and fishing opportunities in Hat Rock State Park, as well as access to the Lewis and Clark Commemorative Trail.

Photo: Danae Abreu/Shutterstock

Under two hours from Hat Rock is the Rock Fort Campsite in The Dalles. The campsite marks the spot where Lewis and Clark rested for three nights, repairing canoes, hunting, taking notes, and meeting with various local tribes. They also stopped here during the return journey. Now, a series of trails wind through the five-and-a-half-acre property, with wayside panels to explain the historical significance. From the campsite you can also get a clear, unobstructed view of Mt. Hood in the distance.

Photo: Sean Pavone/Shutterstock

The next major city you’ll encounter will probably be familiar to you. Entering Portland pretty much marks the moment you can celebrate surviving the wilderness and feel relieved — or saddened — that the end is in sight. You’ve come a long way. Reward yourself with a few local beers at some of Portland’s famous breweries, like Deschutes Brewery Portland Public House, Kells Brewery, and 10 Barrel Brewing. And, of course, don’t skip out on the nightlife. Portland has one of the best live music scenes in the northwest, with a variety of eclectic, unique acts performing every night. Revolution Hall and the Doug Fir Lounge are two of the city’s mainstays, and it’s definitely worth spending a night or two to check them out.

Photo: Jess Kraft/Shutterstock

Even if you’re hungover the next day, the home stretch should be a piece of cake. A drive of less than two hours will bring you the terminus of both your journey and the Columbia River, in the city of Astoria on the coast of the Pacific. This city of 10,000 people isn’t quite as bustling as Portland, but it’s the important home of the Lewis and Clark National Historical Park. The park includes an educational replica of Fort Clatsop, reenactments featuring rangers in period attire firing muskets, and hide-tanning demonstrations. There are also many hiking trails through the surrounding forest, some with beautiful coastal views.

To cap off your epic trip, spend your final night at the Chart Room, the widely beloved dive bar where everyone in Astoria gathers after 1:00 AM. Since venturing into a dim dive bar is basically the modern equivalent of a 19th-century explorer forging through a foggy mountain pass, it’s the ideal way to end your road trip.