The current exhibit at the mahJ, the Museum of Jewish Art and History in Paris, is illuminating and sobering. You’ll recognize the showy colors of Marc Chagall and the emotive faces of Amedeo Modigliani. These artists’ works hang in the world’s important contemporary galleries, like New York’s MOMA, but not always with the context offered at the mahJ exhibit.

Paris's Museum of Jewish Art and History Is a Must-Visit

Chagall and Modigliani were members of “L’École de Paris,” lending the exhibition its name, Chagall, Modigliani, Soutine… Paris as a School, 1905-1940. From the beginning of the 20th century until the onset of World War II, the École de Paris united artists from various countries into a thriving cultural scene.

Photo: Centre Pompidou, RMN-Grand Palais/mahJ

A central message of the exhibit — a theme that is left unexplored elsewhere — is that Chagall, Modigliani, and the other artists celebrated in the exhibition were Jewish.

“They were elegant, very good looking,” said the exhibition’s curator Pascale Samuel, when I asked her if these artists were fully accepted into the Paris art community. We were observing a painting of the well-dressed artists seated together at a café, a place she says was pivotal to the exchange of ideas. Beyond the smart attire, Samuel said many of the artists also brought to Paris skills honed in well-regarded art schools.

“This group of artists was completely integrated,” she said.

That line struck me. My own grandmother was born in Berlin, Germany, brought up in a secular Jewish family in a leafy neighborhood of spacious houses. She, too, was completely integrated. But as Nazism took hold, she was lucky enough to leave the European continent together with her parents and siblings before calamity — spending the rest of her life in Montevideo, Uruguay, where my mother was born.

Decades later, when a German friend traveled with me to Uruguay and met my grandmother, he was dumbstruck. “She is so German,” he had marveled. Of course she was.

photo: mahJ

And of course the Jews who lived in Paris became Parisian. In fact, in the case of many of the artists showcased at the mahJ exhibit, it was a choice they deliberately made — a point curator Samuel powerfully illustrates in the chronologically ordered exhibit.

Many of the Jewish artists who came to Paris arrived from Russia, where they were discriminated against and faced the threat of deadly pogroms, Samuel told me. They were drawn to Paris as an open, modern society.

“They wanted to find modernity, and they wanted to find freedom,” she said.

However, these newcomers would soon confront the First World War — and would have to choose between returning to their home countries or remaining in France. “Most chose to stay in France and join the French army,” said Samuel, noting that it was a crucial development. “It’s the moment of the complete integration in the French society.”

Up to 85,000 foreign-born Jews ended up joining the French army — earning the right to citizenship after the war. Lest we think, however, that members of the L’École de Paris were only men who could choose to enlist, every room of the exhibition also includes at least one female artist — something Samuel stresses she did deliberately.

“It’s important to have a woman’s perspective about Paris and not only [that of the] men,” she said.

Photo: Musée du Petit Palais/mahJ

Women like the artist Marevna weren’t afraid to show the banal horror of war as in the painting showing a soldier both simultaneously maimed and dead, in the company of a woman in a gas mask.

One of the best known of these women artists was Chana Orloff, many of whose marble and bronze busts are on display. Samuel noted that Orloff’s sculpted portraits were in high demand among intellectual circles, and her subjects included Modigliani, Anaïs Nin, Pablo Picasso, and Henri Matisse.

While the mahJ’s École de Paris exhibit wraps up this weekend, some works by Orloff, Chagall, Chaim Soutine, and other groundbreaking artists remain as part of the museum’s permanent exhibit. But as the name of the museum makes clear, the mahJ also looks not just at Jewish art but its history.

You’ll see in the permanent exhibit artifacts depicting Jewish life in France from the Middle Ages to the present. Centuries-old paintings of marriages, a funeral, and other religious rites sit alongside arks holding Torah scrolls and Hanukkah candelabras. Not all the items are French in origin. There is Italian furniture used in a synagogue during the Renaissance and, from Germany, a rare wooden Sukkah, a normally temporary structure used for families during the festival of Sukkot.

While the items are sourced from several places, Samuel stressed that Judaism has deep roots in France itself — noting that Jewish tombstones found in Paris date to as early as the 1200s.

“It is important to say that French people, Jews, lived in France for a very long time,” said Samuel.

Photo: Adagp/mahJ

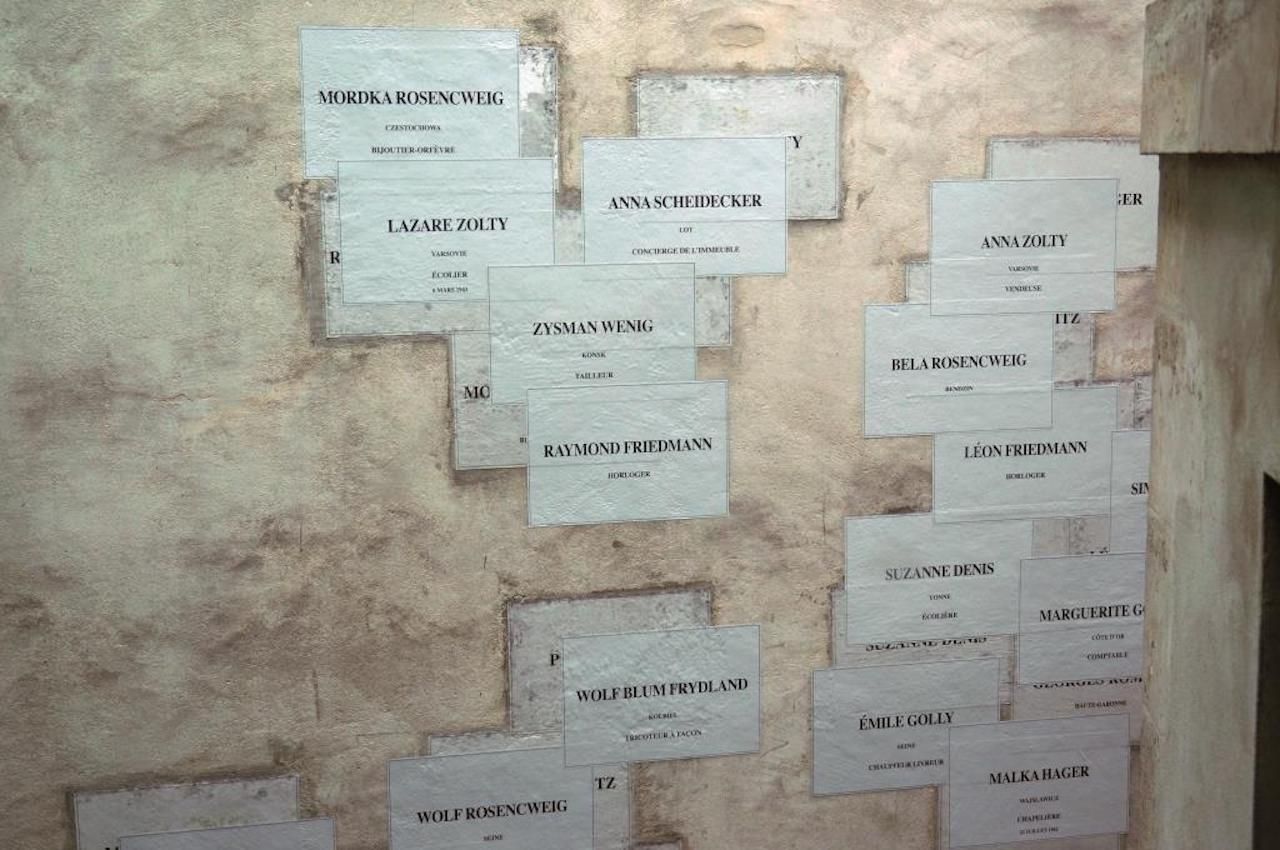

Some of them even lived in the 17th century building that houses the mahJ, the Hôtel de Saint-Aignan. The artist Christian Boltanski has created a tribute to the 1939 inhabitants on the walls of a lightwell that you can observe from within the building. Placards list their name and their profession, such as hatmaker or tailor. Where known, also listed are their date of birth and the date Nazis took them away.

“It’s a paper monument,” said Samuel of the placards. “That means we have to replace it every two years. It’s important not to forget.”

I looked out the window at the names on the wall and thought of my own grandmother. How was she remembered in Germany? Today, Berlin is full of moving memorials to those whose lives were shattered by Nazism.

But sometimes to see the many, you need to see just one. For my German friend, the Jews murdered by and exiled from a country he was born into decades later remained abstract. Meeting my grandmother and noticing the same mannerisms and attitudes he’d find in a woman of her age in his country revealed to him in a visceral way the depravity of the idea that she, for being Jewish, did not belong where she had been born.

While Holocaust Memorials are necessary, so are museums like Paris’s Museum of Jewish Art and History. By seeing the daily rituals of Jewish life in Europe, it establishes the humanity of the many residents of Europe. And by celebrating their art, it emphasizes their contributions to the society they lived in.

Photo: Giovanni Novara-Ricci/mahJ

Certainly, the majority of the Jews in L’École de Paris came from other places. But they weren’t the only foreigners. Piet Mondrian was Dutch and Picasso, who together with Matisse was considered a leader of the movement, was from Málaga, Spain. And still they belonged to the Paris School.

In fact, Chagall (originally from Belarus) was so devoted to his new home in France that he painted himself as the Eiffel Tower on the cover of a Yiddish magazine on display at the L’École exhibit.

“He loved Paris so much. He wanted to stay so much,” said Samuel.

But, as happened all over Europe, and as the L’École exhibit goes on to show, Nazism would make that option impossible.

With the looming approach of World War II, the Jews who had made Paris their new home for decades — some of them even fighting in uniform for France twenty years earlier — had only one viable option: Escape.

Towards the end of the exhibit is a painting of the port city of Marseilles alongside a letter, dated September 1940. It’s from the artist Moïse Kisling to his wife Renée. He is Jewish, she is not. He is getting ready to sail away from France. In his words you see his pain at leaving her and their two children.

“We understand when we read that letter how painful it was for them,” said Samuel. “They wanted to stay in France. They wanted to be French. They wanted to be free.”

“But they had no choice,” she added. “They were murdered or they left.”

Photo: Noelle Alejandra Salmi

The last image in the L’École exhibit is a black wall with black and white photographs of 108 pieces of art. There are no names. But each piece of art was made by an artist who was in France during the heady times of L’École de Paris and who did not leave. Each was killed by the Nazis.

It’s a shame this sad and beautiful exhibit, two years in the making, will soon be gone.

But the mahJ and what it has to teach us remain. If you can’t go in person, you can explore it online. You can schedule for a group or join online guided tours on select Sundays of the year.

And if you are in Paris, head to the mahJ. It’s located in the city’s Jewish Marais neighborhood, where just steps away are shops selling kosher deli foods or falafel. In fact, I had the best falafel I’ve had there since the one I enjoyed on a business trip to Israel years ago.

But the Jewish Marais also has bakeries with the luscious, flaky pain au chocolat pastries I dream of every time I come to France. The Jews there are also French, after all.