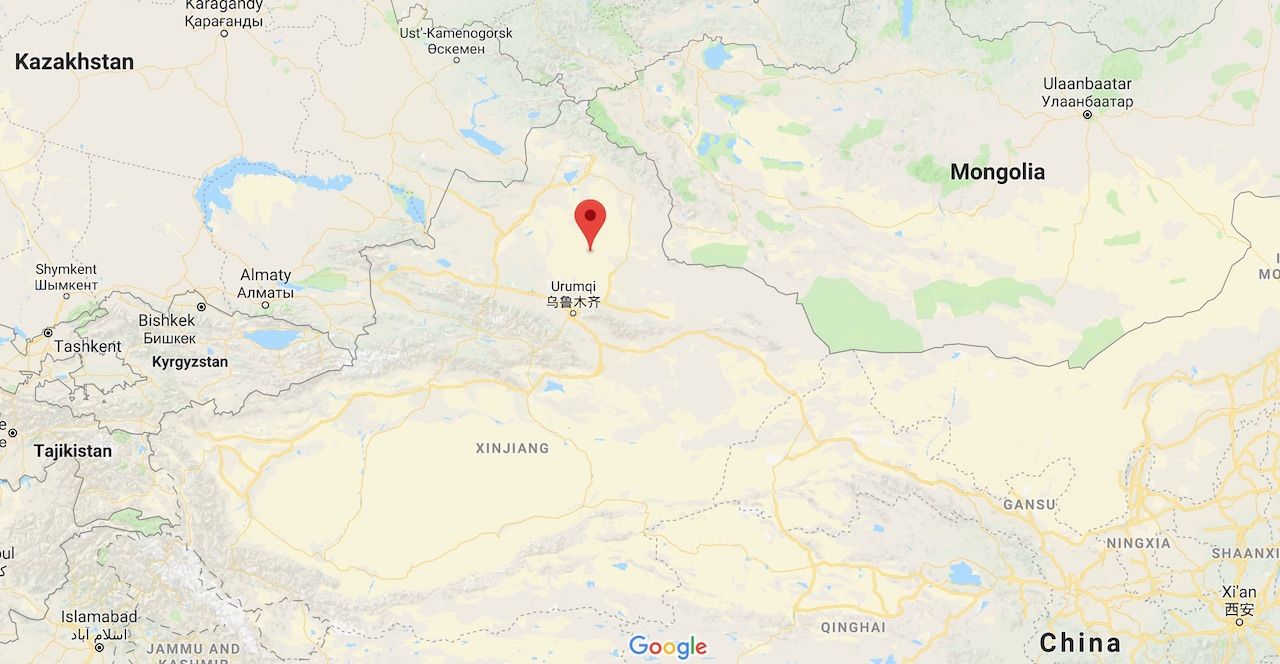

It turns out that the “middle of nowhere” is actually somewhere very specific. Located in the corner of China that is bordered by Mongolia, Kazakhstan, and Russia, the Eurasian pole of inaccessibility redefines the benchmark for “remote.” The farthest point from any sea or ocean on the planet has always been on the bucket list of geography nerds and explorers, and as the name suggests, reaching it is an adventure not without obstacles.

How to Plan a Trip to the Eurasian Pole of Inaccessibility

What is a pole of inaccessibility?

The poles of inaccessibility are the points on the map considered most difficult to reach because of their distance from any coastline. But determining how hard it is to actually travel to these locations is subjective, and although some of them are easy enough to visit, others are truly isolated from civilization. Each major landmass has one, with the northern and southern poles of inaccessibility being the least accessible.

In Antarctica, a bust of Lenin emerges from the frozen landscape, looking ahead toward Moscow in what is the southern pole of inaccessibility. In the Arctic, the situation gets even more difficult: with ice-sheets melting due to global warming, the northern pole of inaccessibility does not have a permanent position. Today it’s found at 270 miles from the North Pole, according to expedition group Ice Warrior, but it is not possible to predict where it will be in the future. The Arctic pole of inaccessibility is also the only one yet to be conquered, although British adventurer Jim McNeill has already attempted the mission twice (in 2003 and in 2006), and is planning a third expedition to get to “the last significant place on earth as yet unreached by mankind.”

The American poles of inaccessibility are still pretty out of the way, but at least you won’t have to risk frostbite or fighting a polar bear in order to get there. North America’s pole of inaccessibility is situated near the town of Allen, in South Dakota, while in South America you will need to travel deep into the Brazilian hinterland to reach the municipality of Diamantino and get to the spot most distant from the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

Photo: Google Maps

Photo: Google Maps

The African pole of inaccessibility is located in the eastern part of the Central African Republic, near the borders of South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Getting there will not be difficult solely because of the lack of roads, but also for the unstable situation of the region. In Australia, however, you can simply drive to the pole from Alice Springs in less than seven hours.

Photo: Google Maps

Photo: Google Maps

The Eurasian pole of inaccessibility

The Eurasian pole of inaccessibility is unique not only because it represents two distinct continents, Europe and Asia, but also because recent research has found that the original location of the pole may have been miscalculated. Three separate spots share the title now, all in the northern part of Xinjiang, in western China, and all are found at least 1,550 miles from the coastline.

The spot believed to be the Eurasian pole until 2007 is located in the Gurbantünggüt Desert near the border with Kazakhstan, however, this calculation is based on the assumption that the Gulf of Ob is not part of the ocean. By accounting for the Gulf of Ob as part of the Kara Sea, the pole shifts dramatically to the south. The Scottish Geographical Journal proposed two points, called EPIA1 and EPIA2, as the farthest from any coastline in the world, respectively 270 and 97 miles away from the original pole.

EPIA1 (44.29N 82.19E). Photo: Google Maps

EPIA 2 (45.28N 88.14E). Photo: Google Maps

How to get there

To reach EPIA1 and/or EPIA2, a GPS is essential, as neither is marked. Even with coordinates at hand, however, getting there will be pretty hard considering that the points are not connected by any road or track.

The closest city to both EPIA1 and EPIA2 is Ürümqi, the capital city of the vast region of Xinjiang, home of the Uyghur people. Once a central point on the Silk Road, Ürümqi sits at the end of the Hexi Corridor, the passage opened during the Han Dynasty in 130 BCE that connected Eastern and Western civilizations.

Zhangye Danxia National Geological Park (Photo: Angelo Zinna)

Although it may appear isolated, reaching Ürümqi is fairly easy today from any direction. Coming from coastal China you will have to cross the Gansu province on a long train ride before entering Xinjiang. If you’re starting your journey in Xi’an (home of the terracotta warriors), consider stopping at the Zhangye Danxia National Geological Park, part of the UNESCO-listed Danxia region, where rainbow-colored rock formations await, as well as to Turpan, a historical city on the Silk Road, famous for being one of the few places in the world below sea level. The flaming mountains and ruins of ancient cities in Turpan are seriously impressive and should be considered when planning your itinerary.

Id Kah Mosque of Kashgar (Photo: Abd. Halim Hadi/Shutterstock)

If you’re traveling from Central Asia, it is possible to enter China via Kazakhstan or Kyrgyzstan. A weekly direct rail connection exists between Almaty and Ürümqi. If you’re coming from Kyrgyzstan, it’s worth stopping in Kashgar, the millennia-old city in the Chinese Far West which has the Id Kah Mosque, built in the 15th century. From Kashgar to Ürümqi, the journey will take between 24 and 30 hours, depending on the type of train you take.

Tien Shan mountain range in Central Asia (Photo: Iryna Hromotsk/Shutterstock)

EPIA1 is found close to the Kazakh border on the Tien Shan mountain range, not far from the Daheyanzi Motorway Interchange in the Bortala prefecture, on the G312 road that connects Ürümqi with Sayram Lake and then Almaty. Although only 18 miles separate the point from the interchange, you will have to climb up an 8,800-foot mountain to say you’ve been there. Definitely not recommended.

To reach EPIA2 it won’t be necessary to pack your mountaineering gear; however, you will have to find your way to the middle of the Gurbantünggüt Desert — the second largest desert in China after the Taklamakan. From Ürümqi the China National Highway 216 crosses the desert to Altay City; your best shot at reaching the Pole, about 100 miles from Ürümqi, is to follow the highway north, to then enter the desert and cross the remaining 50 miles with a four-wheel drive.

Know before you go

- Although distances can be huge, traveling by train is a great way to experience China. The rail system is well developed and the trains are clean, comfortable, and still relatively cheap. Unfortunately, foreigners cannot buy tickets online from the official Chinese railway website as a local credit card is required, but many agencies offer this service for a fee. Some of the larger cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Xi’an have an English-speaking window at the station, though this is not seen elsewhere. A good idea is to get your hotel to write down what ticket you’d like to buy in Mandarin and hope it is still available.

- Most Chinese trains have four classes to choose from, depending on how far you are traveling. For short trips, you can pick a “soft” or a “hard” seat. These labels indicate the first and the second-class carriages, and despite the name, the hard seats are padded. The same goes for overnight rides, where you can select a “soft sleeper” or a “hard sleeper.” The difference is that by buying a soft sleeper ticket you will travel in a four-berth compartment, and with a hard sleeper ticket you will be in an open-plan carriage. A decent mattress, clean sheets, and pillows are provided no matter what class you choose.

- The conflict between the local Uyghur population and the central government has caused numerous accidents to happen in Xinjiang over the past decade. Some travel advisory boards still discourage people from going there, but foreigners shouldn’t consider the political situation a reason not to visit. Xinjiang today is a highly policed territory, and apart from the constant checks, it is unlikely that a visitor will be involved in acts of violence.

- The arid lands west of the Kazakh border seemed to have been long forgotten by the outside world, but it is changing. The Belt and Road Initiative, the largest infrastructure project ever planned, is transforming the region thanks to the trillion-dollar investment China has employed to reconnect Europe with the Far East. The village of Khorgos, just 80 miles from EPIA1, is set to become an “important node on the global economy” because of its role as a trading connection on the new Silk Road, as reported by The New York Times. What will soon become the largest dry port in the world began its activity here in 2015 and is transforming the tiny Kazakh village to allow Chinese trains to transfer their cargo onto Russian trains and then reach Europe. The World Bank collects academic research done on the Belt and Road Initiative (also known as the New Silk Road), with in-depth information on what is happening in the countries involved in the project. The South China Morning Post has created an interactive guide on the five main projects of the BRI.

- A number of useful resources can help you find your way to the Eurasian poles of inaccessibility. Pleco is an app that allows you to easily communicate in Mandarin and translate signs through its OCR technology. Seat61 offers a rich and updated guide to train travel in China. Caravanistan is a comprehensive guide to all Central Asian countries, with first-hand experiences of travelers shared daily on the forum.