HBO Max launched this week, adding to its catalogue nearly every movie made by legendary Japanese animation house Studio Ghibli. Now is the perfect time to binge these classic films, which are infused with magic and adventure, and celebrate the immense power of the imagination to bring not just joy but also refuge from fear and loneliness. The grand cities in which these tales take place might be fictional (in most cases), but their foundation is multicultural, drawing from the architecture and fashion of cities all over the world.

Studio Ghibli’s Global Perspective Celebrates a Multicultural World

Hayao Miyazaki is notoriously anti-war. Most Studio Ghibli films speak out against violence and, in particular, the trauma and heartbreak it inflicts on children. Some of these films do have a distinct sense of place: Grave of the Fireflies, directed by Isao Takahata, who co-founded the animation studio with Miyazaki, for instance, follows a pair of orphaned siblings in Kobe, Japan, as they attempt to survive after their home is firebombed during World War II. Perhaps the most famous Studio Ghibli film, My Neighbor Totoro, the story of two sisters who befriend a friendly forest spirit after their mother falls ill, takes place in Tokorozawa, Japan. And the setting for Princess Monoke is allegedly the Shiratani Unsuikyō forest, a World Heritage site on Yakushima island.

Photo: Studio Ghibli

All Studio Ghibli films are also rooted in a distinct Japanese aesthetic. One aspect of that overarching aesthetic is of course kawaii, the Japanese concept of cuteness, into which Totoro neatly falls with his fluffy, squishy body and perfectly circular eyes. Totoro is the best example, but Calcifer, the blob-like fire demon with the high-pitched voice that powers Howl’s titular moving castle, could be considered kawaii. So could Jiji, the black cat companion who steals the show in Kiki’s Delivery Service.

Wabi-sabi, the Japanese aesthetic principles that celebrate imperfection, impermanence, simplicity, and intimacy, among other concepts, might also be a guiding force behind Studio Ghibli films.

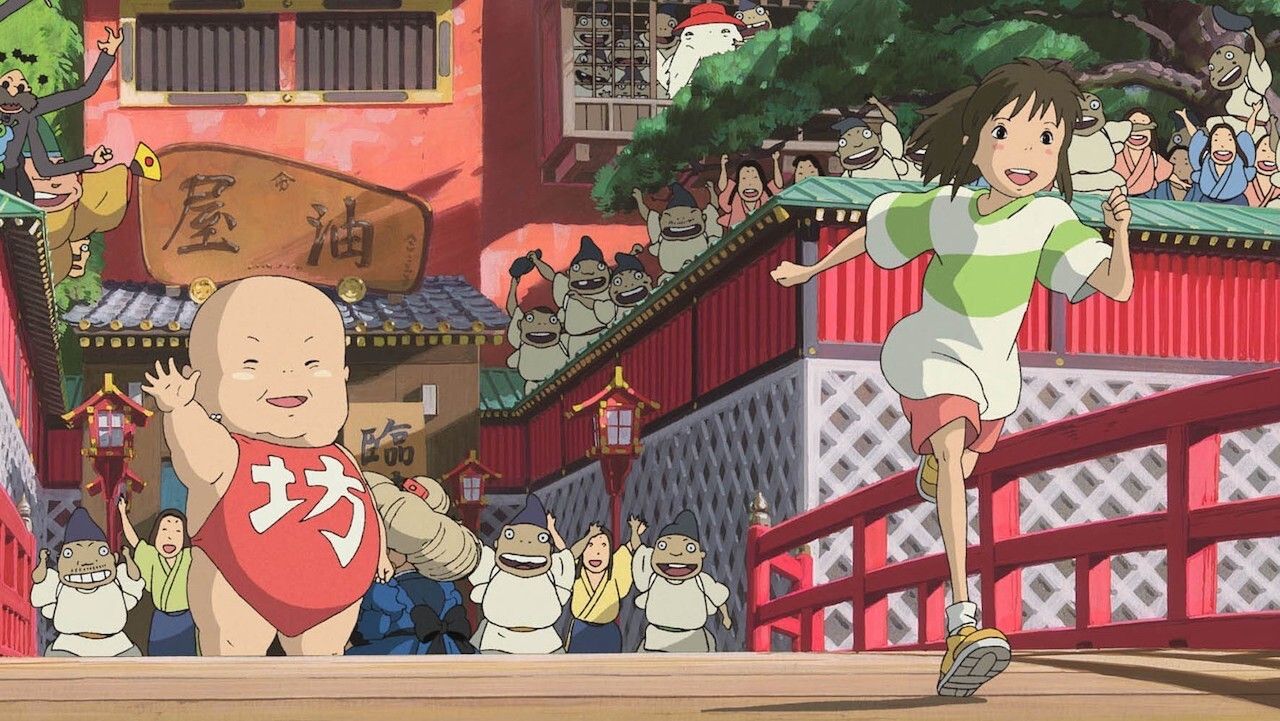

In his book The Japanese Art of Impermanence, Andrew Juniper writes, “If an object or expression can bring about, within us, a sense of serene melancholy and a spiritual longing, then that object could be said to be wabi-sabi.” The bouquet of pink flowers gifted to Chichiro when she moves away from home in Spirited Away (inspired by the deities of Shinto and Buddhist folklore and replete with Meiji period architecture), which she clings to as a reminder of her old friends, and the red radio that Kiki’s father gives her before she leaves home seem to nod toward the principles of wabi-sabi. Both are simple but treasured items that reflect the fleeting nature of childhood, significant transitions in the lives of the characters, and the intimate bonds between loved ones that are tested throughout both films.

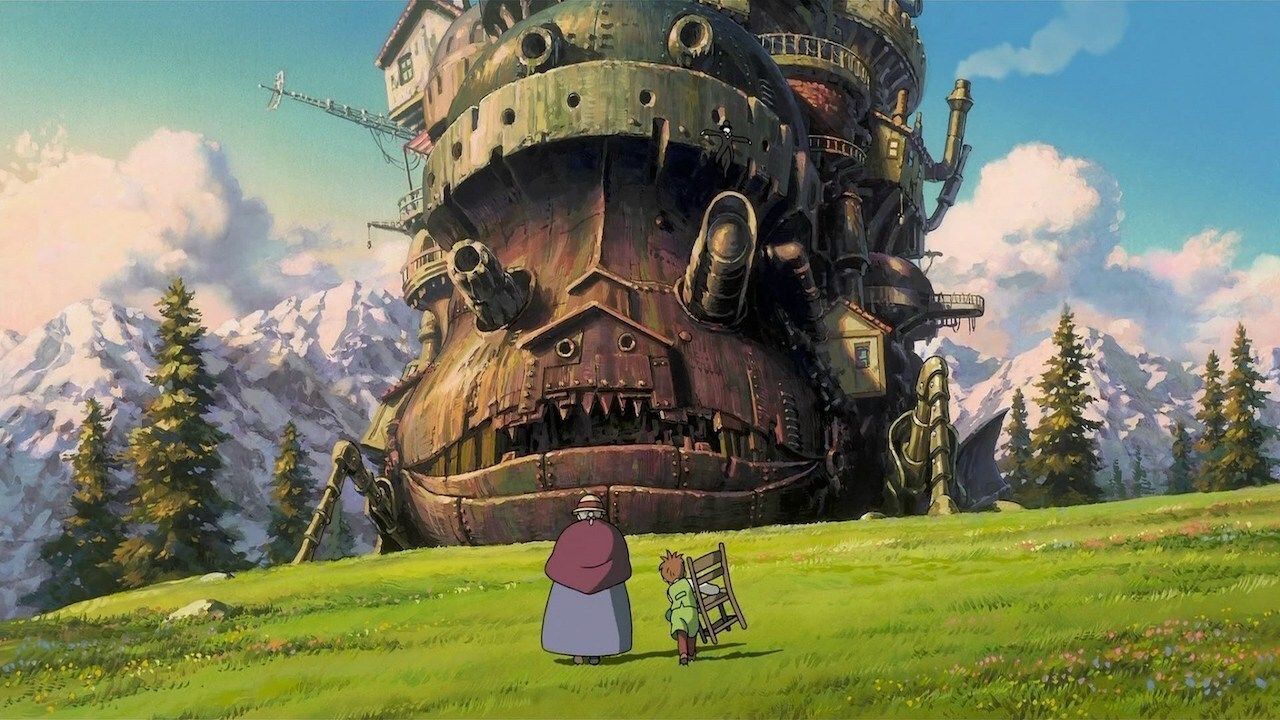

Photo: Studio Ghibli

The way that Studio Ghibli films interpret home also seems to fit into this philosophical worldview: Wabi can sometimes be defined as “rustic simplicity,” which also connotes solitude. Consider the painter Urusla’s home in the woods in Kiki’s Delivery Service, where she communes with nature and contemplates her artwork. Or Howl’s castle, a steampunk multi-level home constructed from steel, wood, old tires, and metal cranes that walks on stilts, belching black smoke from multiple smoke stacks. It embodies transience and imperfection because it is made from found, moving parts cobbled together to make a whole. As Richard Powell writes in his book Wabi Sabi Simple, “nothing lasts, nothing is finished, and nothing is perfect.”

The philosophical and spiritual principles that guide Japanese culture are an essential part of the formula that makes Studio Ghibli films so masterful. However, the animation house has a distinctly international view point, imbuing many of its films with a pan-European atmosphere.

Photo: Studio Ghibli

The opening scenes of Howl’s Moving Castle, for instance, evoke World War I-era Europe: Broad shouldered soldiers in starched uniforms sporting handlebar mustaches march through the streets, conjuring up images of perhaps French, German, or even Austrian soldiers. The architecture feels more Parisian — a canal runs through the neighborhood where the protagonist, Sophie, mends hats for a living. Meanwhile, the high-collared, floor-length dresses and sun hats worn by the women characters would place the film somewhere in the 1870s — long before World War I. That the story itself is based on a book by Welsh writer Diana Wynne Jones adds another layer of complexity.

Howl’s Moving Castle, in other words, moves through cities, cultures, and timelines like Howl himself moves between realms with his magic doors.

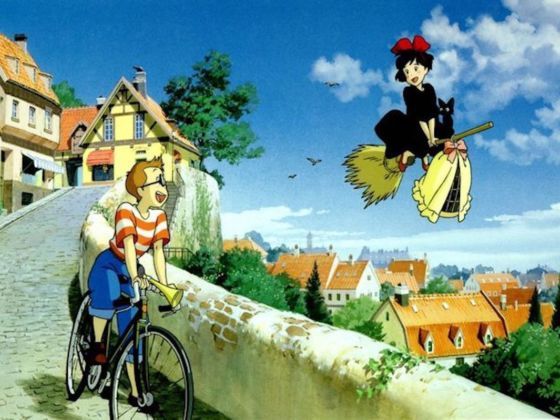

In addition to the clear homages to Europe in Howl’s Moving Castle, the setting for Kiki’s Delivery Service draws from European cities near water. Miyazaki researched the film by traveling to Sweden. The resulting fictional city of Koriko is a mashup of Lisbon, Paris, San Francisco, Milan, and Stockholm. Miyzaki later said the seaside town is bordered by the Mediterranean and Baltic seas. Notably, the film takes place in an alternate universe in which World War I and World War II never took place.

Photo: Studio Ghibli

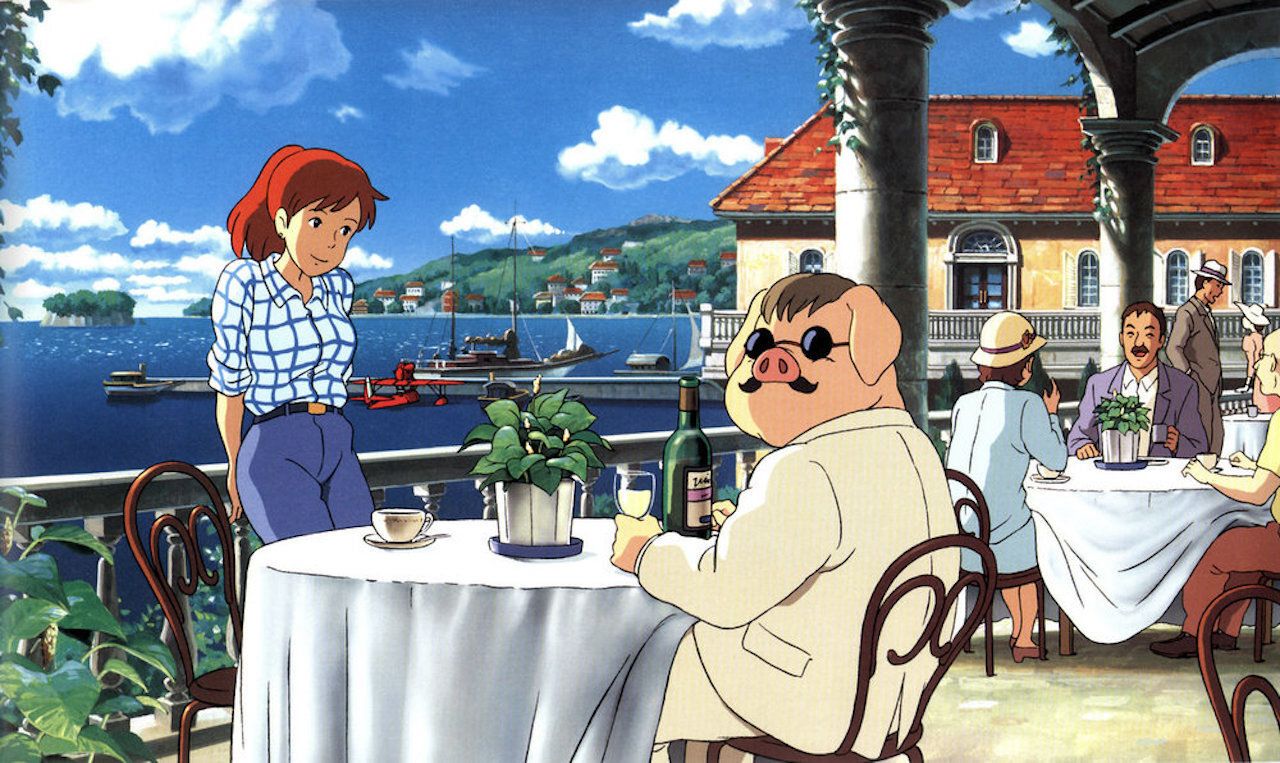

A lesser known, but equally enjoyable Studio Ghibli film, Porco Rosso, follows a once-human Italian fighter pilot who was transformed into a pig during World War I. The story contains a sequence in Milan, and Porco Rosso’s hideout is supposed to be on the Croatian shoreline, while much of the in-flight action takes place over the Adriatic Sea.

Japan has of course served as muse to Studio Ghibli. Yet Miyazaki also pays homage to the buildings, homes, cars, even bakeries of European cities without losing his sense of what home and family should look and feel like. The artistry and magic behind these films is that they are imbued with a sense of timelessness in a fantasy world that is both inclusive and entirely distinctive. Studio Ghibli films transport you to a world that feels familiar, not just in its setting but in its feelings — of childhood and longing and love — but that will leave you tingling from the lasting spell they cast on your imagination.