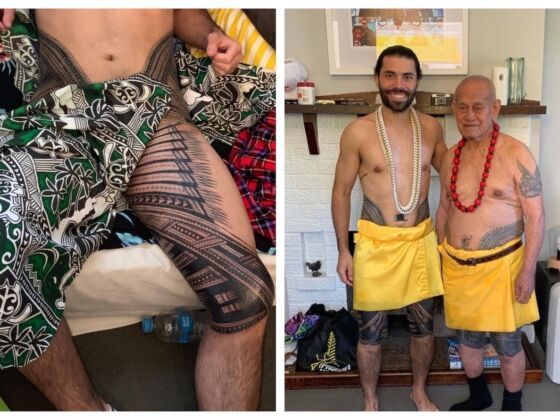

Tattoos have become so ubiquitous that we don’t bat an eye at people with fingers adorned with black ink, full sleeves, or even neck tattoos. It’s significantly rarer, however, to see someone whose entire lower half is covered in ink. Ironically, this much less common sight is among the oldest and most traditional forms of tattooing in the world. The Pe’a is the name of the traditional Samoan male tattoo, covering the whole body from the waist to the knees, and its origins are rooted in Samoan mythology. This Samoan “tatau” is more than just an aesthetic complement to the body — it signifies courage and serves as a symbol of manhood, a rite of passage both beautiful and painful.

The Beauty and Pain of the Pe'a, the Traditional Samoan Tattoo

The Pe’a isn’t just a quick trip to the tattoo parlor. It’s an extensive process that includes flying to a Samoan community, enlisting the aid of an experienced tufuga (tattoo master), and enduring up to two weeks of “tapping.” Braden Ta’ala, a US citizen currently living in Utah, experienced the daunting yet rewarding process first-hand.

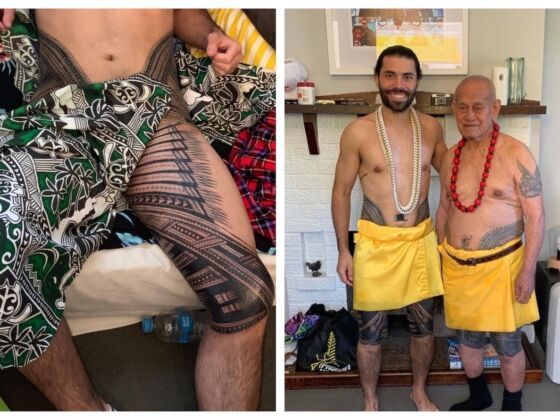

On the right, Braden Ta’ala and his 90-year-old grandpa, both bearing the Pe’a. Photo: Braden Ta’ala/Instagram

Although Ta’ala has lived his whole life in the US, he had always been curious about his Samoan ancestry — especially his grandfather’s Samoan tatau. No men in his family — after his grandfather — had got their Pe’a, and after much research about the tatau’s history and cultural significance, Ta’ala decided to follow in his grandfather’s footsteps and fly to New Zealand for his Pe’a.

Finding a tufuga

The Pe’a is more than a simple tattoo — it’s a journey that begins long before the needle touches the flesh. According to Ta’ala, “the whole process leading up to the actual tapping took around a year of preparation and planning.”

A huge part of this is finding the right tufuga. “There are only two family lines from which the traditional tufugas originated that have passed down the practice to their children, etc,” says Ta’ala. “It was important that I used one of these family lines, just as my grandfather did.”

He continues, “I worked primarily with one of my uncles in New Zealand and used his connections and ties to tufugas in Samoa. We originally planned to fly a Tufuga and his assistants/stretchers from Samoa to New Zealand, but long story short, there were issues, and the day we arrived in New Zealand we had to make other arrangements. By some miracle, we found a renowned tufuga who lived in Auckland on a two-week break between tataus who agreed to do it. And he was amazing. So much experience; his work is gorgeous.”

Photo: Braden Ta’ala/Facebook

Finding the right tufuga is also extremely important because he chooses what the tatau actually looks like. “It is all in the tufunga’s mind and completely up to him,” said Ta’ala. No matter what design the tufuga chooses, however, it always “has specific areas with meaning related to the Samoan culture and significance for how you should live your life.”

Getting the tattoo

Ta’ala started preparing for his Pe’a several months before getting the tattoo itself, including mental preparation and studying for what to expect. As part of the “payment” for the tatau, Ta’ala’s family was expected to not only fly the tufuga and his assistants to New Zealand but also provide them with meals, drinks, and snacks. In Samoan culture, the family (or “village”) of the man receiving the Pe’a serves as the support system for both the man and the tufuga. Ta’ala’s family in New Zealand took two weeks off work to host him and the tufuga and provide for all their needs.

Photo: Braden Ta’ala/Facebook

“The actual tattoo took 10 days from start to finish,” said Ta’ala. “The shortest day was six hours, and the longer days were around 10 hours. There are two people that just stretch the skin to the correct tension, shave, and wipe the blood. They had to do multiple cold showers and massage the tatau with soap to prevent infection. Traditionally in Samoa they’d use the ocean for this part but in New Zealand we did cold showers. In the old days many would die from infection when getting their Pe’a.”

Although tattoos are typically associated with pain, the Pe’a is on a whole different level. The “tapping” method consists of the tufuga using serrated bone combs attached to tortoiseshell fragments with a mallet to drive the combs into the skin. The process is slow, meticulous, and painful. This is where Ta’ala’s mental preparation came in handy.

“The first day went well,” he said, “the adrenaline from years of planning and a solid year of focused mental preparation was paying off. The second morning, I woke with a 103-degree fever, cold sweats, throwing up and my body shaking. I had made a critical mistake — not eating enough for my body to endure the physical trauma.”

This reaction is common during the Pe’a when men fail to eat enough. Ta’ala recovered from this episode after an hour and was “back laying down listening to the recurring, and almost therapeutic, taps of the sausau (tapping mallet) striking the au (comb of needles).”

Ta’ala endured a significant amount of pain over the course of 10 days, but “focusing on the importance and why I was doing this was critical” to getting through it, he said.

It’s more than just a tattoo

The Pe’a is a trial by fire. Those who pass through the flames endure hardship both mentally and physically, but it’s the pain that makes the Pe’a such a meaningful experience.

“These markings are not just a tattoo,” said Ta’ala, “but a reminder of who I am and how I should conduct myself with service and humility to my family and community. These visible marks on my body remind me of the unseen marks of mental preparation, endurance, and control needed to complete the tatau. The internal marks have resulted in a strength that I wouldn’t have received without the extreme level of pain, endurance, and dedication that was required.”

According to Ta’ala, the tatau has recast his approach to life’s challenges and reshaped his conception of his ancestral past.

“It gave me a much-needed understanding of what it means to be a Samoan.”