Egypt is full of incredible sites to visit, from the Great Pyramids in Cairo to the banks of the Nile to Abu Simbel in Aswan. There are temples upon temples, each just as unbelievably impressive as the last, but one site in particular stands out as the perfect place where a person could lose themselves for one entire day — the Valley of the Kings.

How to Make the Most of a One-Day Visit to Egypt’s Valley of the Kings

As its name suggests, it’s an enormous valley where the kings of Egypt who ruled from 1539 to 1075 BCE were buried after their death. Many of them began building their tombs in the valley while they were alive, with sizes ranging from small hallways with a single burial chamber to hundreds of feet long with multiple annexes. It became a Unesco World Heritage site in 1979, and for good reason. It’s a testament to ancient Egyptian history — burial traditions, lifestyles, beliefs, an entire language, and artistry the likes of which we don’t see today.

There are some 60 tombs that have been discovered over the years, and no one can be certain that there aren’t more just waiting to be found; excavation work goes on to this day. Only a small portion of the tombs are open for public viewing, but it can still be daunting to figure out how to organize your visit. To help you plan it all out, here’s how to make the most of your visit to the Valley of the Kings.

- Before you go: the #1 piece of advice before visiting

- The best times to visit

- How to get to there

- Tours

- Must-see tombs

- If you have more time

Before you go: the #1 piece of advice before visiting

Photo: Aryana Azari

Pay attention to the tickets you’re purchasing; otherwise, you may end up unable to enter multiple tombs. While there are well over 60 discovered tombs in the Valley of the Kings, only a small few are open to the public.

It’s worth noting that prices can vary, and the numbers may be different on your future visit. The initial entrance ticket you purchase, which costs 200 Egyptian pounds ($12), will let you pick three of eight tombs to visit. These are Ramses VII, Ramses IV, Ramses IX, Merenptah, Ramses III, Tausert-Setnakht, Seti II, and Siptah. If you’d like to visit all eight, you’ll need to purchase three tickets.

There are three tombs not on the above list that each require a separate, individual ticket that can be added on. You can visit all three, one, or none. These tombs belong to Ramses V and VI, Tutankhamun, and Seti I, and cost 100 ($6), 250 ($15), and 1,000 ($62) pounds respectively.

Additionally, if you don’t want to walk the long distance from the visitor center to the actual valley, you can purchase a tram ticket. When you pass through the visitor center, you’ll see trams taking visitors to and from the valley. The tram ticket costs four pounds ($0.25).

You may or may not need to purchase a photography ticket as well. As is customary among many of Egypt’s famous sites, a photography ticket is needed to be able to take photos and videos. The rules on photography tickets are constantly changing and can be dependent on exactly which site you’re at — sometimes the ticket is required even for cell phone photos, sometimes it’s only for everything but a cell phone, and other times it’s not required at all.

If you don’t see any signage at the ticket booth about it, ask the workers or your guide. If they say yes, get the ticket. Workers will continually ask for it throughout your visit, and some go so far as to make you delete the photo if you don’t have it or take your camera away for pickup later, so it’s best to get one and keep it somewhere that’s easily accessible. The price of a photography ticket is between 300-350 pounds ($18-$22). It’s a small price to pay for memories that will last forever.

It’s important to note that once you arrive where all the tombs are, you will be unable to purchase any more tickets and cannot go back to add on more. That means if you only purchased the initial entrance ticket and then suddenly decide you want to see King Tut’s tomb, you’re out of luck.

The best times to visit

To make the most of your visit and see several tombs, you’ll want to get there as early as possible. Doing so will allow ample time to take everything in, and you’ll beat the crowds — if it does get crowded during your visit, you can use that time to take a break and have a snack. During the summer season, operating hours are 6:00 AM to 5:00 PM, and during the winter season it’s 6:00 AM to 4:00 PM.

Luxor’s high season is from October to February as the temperatures are generally much more manageable, still warm but cool enough that it’s not bothersome. Visiting on the fringes of that seasonal range is your best bet if you’re worried about crowds. Luxor’s low season is the summer months of June to August, and it’s that way for a reason. Summers can be unforgiving with their scorching heat — temperatures can go as high as 106 degrees.

How to get to there

The Valley of the Kings is located on the West Bank of the Nile River, approximately 45 minutes by car from Luxor, one of Egypt’s most famous cities — chances are that if you’re visiting the valley you’ll be basing yourself out of Luxor, at least partially, to also see the many other historical sites near it.

Public transportation is not an option to get to the valley, but there are a number of tour companies that take visitors there from Luxor daily. Some of these are part of multi-day tours, like Timeless Tours, but there are also day-trip options, like the offerings from Egypt Tailor Made. Others can be found through tour aggregators like GetYourGuide and Viator.

The other option is by taxi or car service. Taxis are reasonably priced throughout Egypt’s major cities, but expect to pay a bit more for the longer distance; the ride should still cost under $25 though it may depend on your negotiation skills. You can also hire a driver for the day, which your accommodation should be able to help you with booking.

Tours

Visitors can meander through the Valley of the Kings at their own pace, with or without a guide. Guides are not permitted within the actual tombs, so if you do get a guide, they’ll give you information about each tomb right before you enter them. However, we highly recommend you do get a guide so you have some context for what you’re looking at.

If you’re visiting with a tour company, your guide is already included. If you’re visiting on your own, then sometimes there are guides on site that can be hired. Some will do it for free; others will require a fee. The availability of such guides isn’t guaranteed, so really think about if you want to visit independently.

Must-see tombs

Each and every tomb open to the public is phenomenal in its own right and will not disappoint in the slightest. However, if you’re unable to fit all the tombs into your trip, then these are the ones you should prioritize. And if you have the time to see all of them during your trip, head to these first as they’re some of the more popular and will fill up by midday.

Ramses IV

Photo: agsaz/Shutterstock

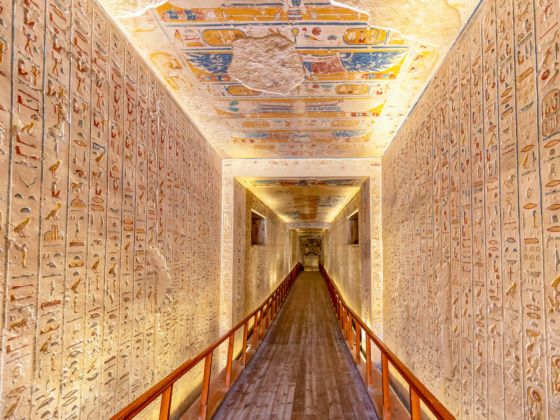

Ramses IV ruled Egypt from 1156 to 1150 BCE. His tomb consists of a single, long hallway that seems to stretch on infinitely before coming to a stop at an antechamber that leads into the burial chamber. While overall it’s pretty simple, the colorful hieroglyphics covering every inch of the walls are what bring it to life. Besides the typical veneration of gods, there are scenes from the Litany of Ra and books of Caverns, the Dead, Gates, and the Night — all funerary texts, commonly displayed in tombs — such as how the dead will be judged and what people can expect in death, as well as scenes from the Ramses IV’s life and his journey through the underworld.

Photo: agsaz/Shutterstock

Even the ceiling is a sight to behold, with depictions of Ramses IV and Ra, the Egyptian god of the sun, becoming one. There’s a fair bit of Coptic Christian and Roman graffiti on the walls, however, such as the scratching out of the Egyptian deities’ faces and drawings of crosses.

The burial chamber is small compared to the hallway and antechamber, and in the middle of it all stands a gigantic sarcophagus. Ramses VI’s mummy is located at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Ramses IX

Photo: Aryana Azari

Ramses IX ruled from 1126 to 1108 BCE. Similar to Ramses IV’s resting place, Ramses IX’s tomb is simple but beautiful. The visit to this tomb is a short one, so it can easily fit into any itinerary, but what makes it worth checking out is the burial chamber at the end of the hallway (the mummy can be found at the Egyptian Museum). Much smaller than average burial chambers for rulers, the hieroglyphics here are not as vibrant as some others but display an interesting series of images. In addition to scenes from the Book of the Earth, there are images of Egyptians on sun boats — barges thought to be used by Ra to move through the skies.

The ceiling’s scene is astronomical in nature, with images of the sun’s nightly journey through the body of Nut, the goddess of the sky and heavens. Some believe that she consumed Ra every night and then gave birth to him in the morning, and the reverse being true for the moon god, Thot. Nut is a common figure that appears in tombs because she was believed to protect the dead until they were reborn into the afterlife.

Merneptah

Photo: agsaz/Shutterstock

Merneptah was one of Ramses II’s sons and ruled from 1213 to 1203 BCE. While the lower half of many walls have been damaged by floods, the hieroglyphics will still pique your curiosity. The most interesting part of this tomb, however, is not even the hieroglyphics — it’s its sheer size. Merneptah’s tomb is utterly, though not as large as his father’s nearby. There are multiple corridors off the long hallway, and the burial chamber itself has several annexes; one of the corridors is even dedicated to Merneptah’s father.

Photo: agsaz/Shutterstock

The burial chamber’s decorations are mostly gone, though remnants on the upper half of the walls still remain. Merneptah was buried within four sarcophagi, each larger than the last; his mummy is now at the Egyptian Museum. The lid of his second sarcophagus can be seen on the left side of the pillared chamber, made with red Aswan granite, and is intact due to restoration efforts. The top of the lid takes the shape of Merneptah, holding a crook and flail. His sarcophagi were so big that pillars and doorways had to be removed just to be able to move them in and out.

Tutankhamun

Photo: Sergei Butorin/Shutterstock

Arguably one of the best-known and popular Egyptian rulers, if not the most, the world has been gripped with a wild fascination for the boy king. Tutankhamun ruled from 1333 to 1323 and died at just 19 years old. It’s hard to define exactly why the world feels so strongly about Tut, but his tomb’s discovery in 1922 was one of the most significant.

His tomb, unlike so many others in the Valley of the Kings, was almost completely untouched. Found were thousands upon thousands of treasures that were buried with Tut, from jewelry to clothing to furniture. The tomb has been robbed at least twice in its existence and was resealed after both times, though robbers never made it to Tut’s greater treasures past the antechamber. Why, exactly, it’s so intact is unknown, though some theorize it could be due to its low-profile location, being accidentally buried by workers who were working on other tombs nearby, or the robbers being caught in the process.

Photo: Nick Brundle/Shutterstock

The treasures have since been moved to the Egyptian Museum and will be transferred to the Grand Egyptian Museum once it opens. Also found in their original state and location were his sarcophagi and mummy. The innermost sarcophagus, its gold still glistening even after some 3,000 years, still sits in the tomb today (the others have been moved to the museum), as does his mummy.

Entering his tomb requires a steep descent down a long stairway, and only one room is open to the public — the one with his sarcophagus and mummy. While small, the room is absolutely breathtaking. The hieroglyphics are still flawless and vibrant beyond belief, with not a single mark of graffiti or face scratched off. The only mark they have is that of time, with some of the paint eroding in places.

Pictures in this tomb, as well as any of the extra ones not on the entrance ticket, are generally not allowed. While Tut’s tomb is an additional fee, it’s worth every single cent.

If you have more time

Tausert and Setnakht

Tausert ruled from 1193 to 1190 BC and was succeeded by Setnakht, who ruled from 1190 to 1187 BC. The particular tomb that they share has a complex history as its construction began two rulers before Tausert herself and was finished once she became queen. The previous rulers were going to use it, but it was unfinished during their time, so Tausert ended up being buried there instead.

Setnakht began building his own tomb during his reign, but it wasn’t finished before he died and his burial for unknown reasons. Setnakht’s son and successor, Ramses III, decided to bury Setnakht in Tausert’s tomb and take his father’s tomb for himself.

Before you enter the tomb, you’ll ascend a staircase to reach a higher point in the valley, and then descend deeper down once you’re inside it. Most of the design from Tausert’s plan for the tomb stayed the same even after Setnakht usurped it, save for some of the hieroglyphics with her name that were changed to Setnakht’s. Images of Tausert among various deities were also visibly plastered over to show a king, rather than a queen, for Setnakht. A sarcophagus can still be found in one of the burial chambers; to this day, neither of the two mummies have been found and identified.

Ramses V and VI

Photo: Jakub Kyncl/Shutterstock

Ramses V (ruled 1150-1145 BCE) and Ramses VI (ruled 1145-1137 BCE) shared the same tomb. It was built during Ramses V’s reign for him, and it’s unknown why his successor, also his uncle, decided to just enlarge the tomb and be buried there rather than build his own. The double interment meant the tomb was larger than most, and it’s speculated that this tomb’s close proximity to that of Tutankhamun’s is why the latter went unnoticed by robbers.

Photo: Jakub Kyncl/Shutterstock

The hieroglyphics along the nearly 400-foot-long hallway have sustained some damage over the years, and their colors have faded away somewhat, but the further in you go, the more intact they seem to be. It culminates in the burial chamber at the end, which contains an unfinished pit in the center and a sarcophagus that was broken by robbers. Both mummies have been recovered and are located at the Egyptian Museum. The ceiling of this room is similar to that of Ramses IX’s tomb, with the image of Nut and the heavenly bodies’ journey but on a much larger scale.

Valley of the Queens

Photo: Oleg Elkov/Shutterstock

Just as the kings have their spot, so do the queens. Just a few miles away from the Valley of the Kings is the Valley of the Queens, where queens, princesses, and other nobility from the 11th and 12th centuries BCE were buried. While its tombs are not as ornate as that of its counterpart, there are more than 90 known tombs. Of the tombs, the one for Nefertari, Ramses II’s favorite wife, is the most popular. Hieroglyphics of Nefertari being guided by the gods, in addition to the typical funerary text images, can be seen on its walls.

Valley of the Queens is open from 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM. Entry costs 35 pounds ($2), and to see Nefertari’s tomb will require a separate ticket that costs 100 pounds ($6). If you’re willing to pay an extra 25 pounds ($1.50), you can also visit the Deir El-Medina, which is an area just a little off the road leading to the tombs that contains a Ptolemaic temple dedicated to Hathor, the Egyptian goddess of the sky, women, fertility, and love, as well as ruins of the village that used to house the workers who built both valleys and their tombs.