Chernobyl’s Exclusion Zone, the quarantined area surrounding the power plant where one of the worst nuclear disasters in history took place, sees way more traffic than the name might suggest. Since the site opened to visitors in 2011, a growing number of tourists have come to northern Ukraine armed with cameras and Geiger radiation counters to visit the rusting remains of the ghost city of Pripyat. It is estimated that in 2017 alone 50,000 people visited the area that was evacuated after the No. 4 reactor explosion, a number three times greater than in 2015. Traveling to Chernobyl today is easier and safer than one might think, with tours departing daily from the capital city of Kiev and infrastructure set up to welcome tourists in the somber Soviet wasteland that was left abandoned after 1986.

How to Visit Chernobyl Safely and Legally

What happened in Chernobyl

Photo: Angelo Zinna

The Chernobyl nuclear power plant consisted of four reactors built between 1970 and 1983 (with two more under construction at the time of the accident), located about 80 miles from the capital city of Kiev. Due to a failed test that was meant to determine how turbines would react to an electricity blackout, on April 26, 1986, the No. 4 reactor at the power plant exploded causing what is considered to be one of the most disastrous nuclear accidents in history.

When the lid of the reactor blew off, vast amounts of radioactive materials were released into the atmosphere. The settlement of Pripyat, a town of 49,000 inhabitants built especially to house Chernobyl’s workers and their families, was the first to be evacuated. According to the World Nuclear Association, in 1986, about 116,000 people were evacuated from areas surrounding the reactor (an area now known as the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, today a military-controlled ring with a 19-mile radius from the power plant); after 1986, about 220,000 people had to leave from Belarus, the Russian Federation, and Ukraine. 30 employees of the power plant and firemen died within a few days or weeks of the accident, and 28 of them suffered from acute radiation syndrome.

Chernobyl today

Today, nature has repossessed the Exclusion Zone and where Pripyat once stood, and a collection of dreary, abandoned buildings filled with rubble have become an unusual attraction. Twenty-five years after the accident, in 2011, Chernobyl opened to visitors after a number of safe itineraries were traced. Since then, a steady stream of tourists have reached the 10-kilometer zone, the inner area which suffered the most from contamination. Although the 1,000-square-mile Exclusion Zone remains quarantined and policed by guards who allow access only to those in possession of a special permit, a small group has chosen to stubbornly return to their original homes. In 2015, The Guardian claimed that 130 people lived in the CEZ; many of them returned to their homes soon after the nuclear accident, unafraid of the invisible nuclear hazard and unwilling to go through the trauma of relocation.

In the background, the New Safe Confinement shelter covering the No. 4 reactor. (Photo: Angelo Zinna)

In 2017, the New Safe Confinement shelter (a huge steel structure) was placed on top of the No. 4 reactor to protect the region from contamination for the next century. The first reactor was operational until 1996, the second shut down in 1991, and the third kept running until the end of 2000. Since then, Chernobyl has remained dormant.

But the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone is much more than a magnet for dark tourists. According to National Geographic, the area has become a unique wildlife sanctuary. Researchers from European universities have been studying animal life in the contaminated area, noticing a substantial increase in the population of different species of large mammals. Boars, wolves, bison, raccoon dogs, foxes, and Przewalski’s horses inhabit the area today, offering insight into the long-term effects of radiation exposure and human-free habitat.

While the fauna may appear to be thriving in a hostile environment and small groups of people are going back to abandoned villages, in 2005, the World Health Organization estimated that 4,000 people could eventually die because of the radiation produced by the nuclear explosion.

Visiting the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

Photo: Angelo Zinna

Although there are reports of people breaking into the perimeter of the CEZ, the only legal and safe way to see what is left of Pripyat and its surroundings is through a licensed tour. While the levels of radioactivity on the prescribed routes are within the limits of safety (at times even lower than in Kiev), hotspots are still present, making a guide who knows the area absolutely essential. Group tours depart daily from Kiev, but it is also possible to rent a guide for private or multi-day trips.

A visit to Chernobyl typically begins with obtaining a permit, which is easily done via travel agents when booking a tour at least two days before departure. A two-hour drive leads to the Dytyatky checkpoint at the entrance of the CEZ, where you will be asked to show your passport. Companies require tourists to wear long sleeves, trousers, and closed shoes, and it is forbidden to touch or remove anything from the area.

Day tours with SoloEast Travel usually last between 10 and 12 hours and stop in small abandoned villages such as Cherevach and Zalissya before reaching the second checkpoint that allows entry to the 10-kilometer zone. The buildings, cars, and roads of these disappearing hamlets are being swallowed entirely by the flora. Before reaching Pripyat, the highlight of any visit to Chernobyl, the tour will take you outside the 35,000-ton steel encasement that covers the No. 4 reactor, showing from a distance the site where the explosion took place.

Photo: Angelo Zinna

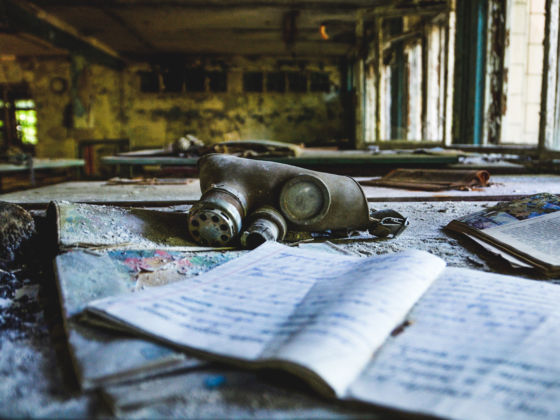

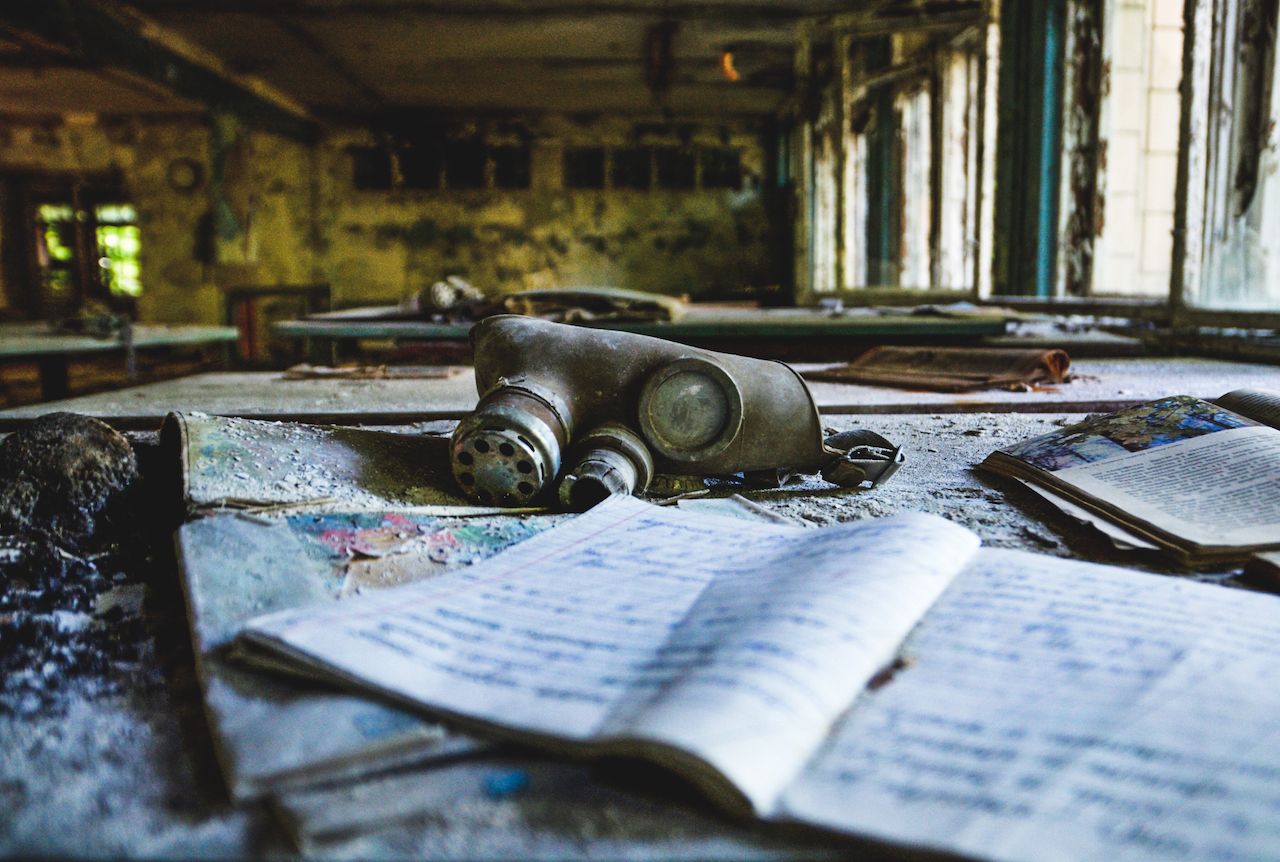

In what is left of Pripyat, vegetation is, at first glance, the only indication that time has passed. Restaurants, schools, and housing blocks stand grimly among tall trees and rusting streets lamps. Although entering the buildings has been prohibited since 2012, guides do take groups inside gyms, kindergartens, and the hospital, and the impact of mass tourism in these eerie spaces is clearly perceptible. A few steps inside the decaying classrooms are enough to understand that gas masks and rotting dolls are placed in a way-too-photogenic position to have been left like that by panicking evacuees.

Photo: Angelo Zinna

A sea of gas masks, allegedly kept under the student’s desks during the Cold War in case of a nuclear attack, covers the floor of one of the classrooms. On a row of chairs placed parallel to the wall, stuffed bears and broken dolls sit in a creepily ordered fashion. Propaganda posters decorate the spaces while plaster crumbles. Pripyat’s interiors remind us that the city may be less ghostly than what it appears to be from the outside. That said, the Instagram-friendly compositions do not render the experience less fascinating. Imagining that 49,000 people lived here unworried until the fateful day is still chilling.

Photo: Angelo Zinna

Most tours include a visit to the Duga Radar, a huge metal structure hidden deep in Chernobyl’s forest, built by the Soviet Union to intercept long-range missile threats coming from the West. Erected in 1972, the 492-foot-tall secret station became known as the Russian Woodpecker because of the repetitive sound emitted from the radar. Upon discovery of the Duga, a defense weapon that never truly worked but is said to have cost more than the power plant itself, conspiracy theories started circulating. The radar was described as a mind control system created to influence Americans, but was never much more than a gigantic waste of steel.

Before exiting the CEZ, you will have to go through a radiation check. Scanners are placed at the checkpoints on the road to Kiev and will detect traces of radiation that you may have come into contact with.

Know before you go

Visiting Chernobyl is safe. The radiation levels in most areas surrounding the power plant are comparable to the natural background radiation found all around us. While there are some dangerous hotspots, you will not be taken there.

SoloEast offers day tours to Chernobyl from Kiev starting at $81, going up in the hundreds for overnight or private trips. Some companies, such as CHERNOBYLwel.come, offer excursions inside the power plant as well. People under the age of 18 are not allowed inside the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.