The tangled historical roots of the idea that “a picture is worth a thousand words” begin with the 6th-century BC Chinese sage Confucius and end with the 20th-century American advertising guru Frederick R. Barnard. Where the idea began is less important than that it survives.

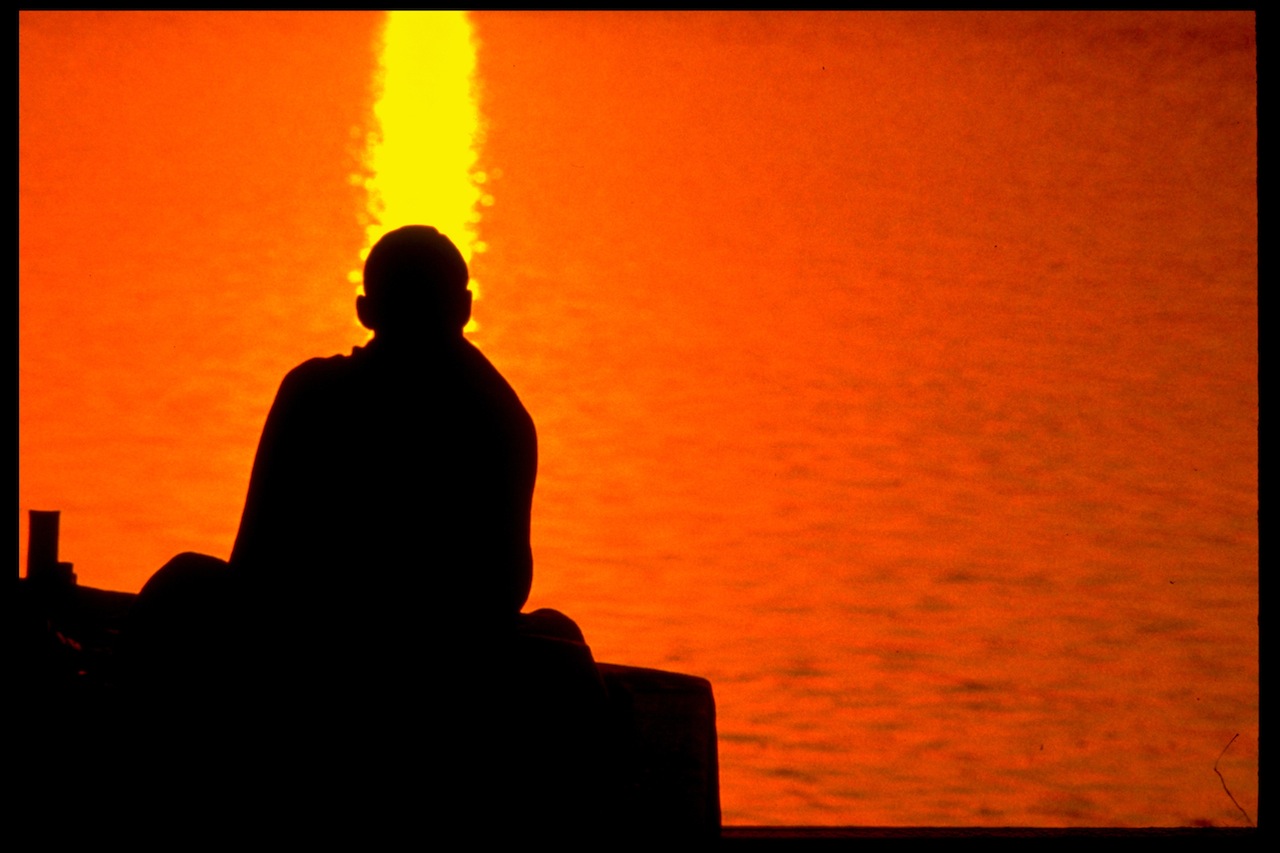

In meditation this morning I was reminded of the moment between breaths. It is short, seldom conscious. It is in that moment that the archer releases his arrow. It is the moment when decisions are, not made, but personally ratified. It is a moment of conception.