“So, how did you get here?” The elderly gentleman looked at me with his kind but clueless eyes, expecting me to tell a refugee story of crossing the ocean before making it just in time for my Ted talk in New Hampshire. Despite the ongoing tragedy of the Syrian humanitarian catastrophe and misperceptions of Muslims, Arabs, and Syrians in the U.S., I burst into laughter. “On a boat,” I replied, laughing. The question was so funny and yet so tragic, reflecting a total lack of understanding and a profuse sense of “them” vs. “us,” that I had to reply with humor.

Becoming a Citizen of the U.S. Meant Being a Citizen of the World

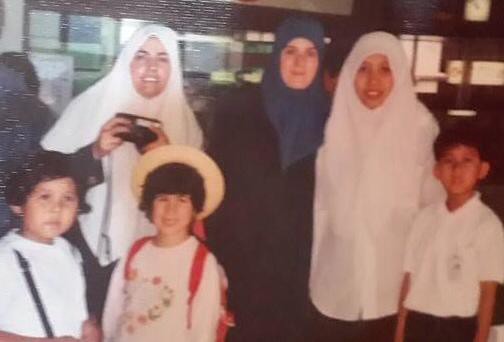

My husband and I immigrated to upstate New York 18 years ago with our three children in tow.

The United States was one of the last places on earth we ever considered moving to. For me, as a Dane, we grew up resenting the big boss attitude of U.S. foreign policies in the ’70s and ’80s, and my husband assumed that the U.S. was unfriendly and that as a Syrian, he would never feel welcome. Funny to think back to how we felt and the misperceptions we had until we visited the country on a trip to California during a time when we were reconsidering if we should stay in Japan.

Japan had been a place we’d called home happily for almost 10 years for studies and work, but now we faced the question of moving somewhere else on earth to grow our family and settle down.

Our visit to California changed everything. American people were not only polite and smiling, but they were welcoming, open, and confident. We loved the outgoing attitude and the sense of community we felt. So ultimately, the American people sold us on uprooting and coming to the U.S.

We more or less literally picked up the stakes and moved, from being employed and well-off with a nice chunk of savings, to learning how to live in a tiny, run-down college town in upstate New York, getting hit by the ice storm of the century that first winter in ’98. It meant surviving off our savings, since my husband’s new job barely paid, and I had taken up my studies while also being a day care provider. Before we arrived in America, we had worked our way up, but we considered ourselves blessed to have arrived in the U.S. educated and with some savings, as well as the best capital of all — our children, and lots of drive!

Coming to the United States, we never really considered how long the process to become eligible voters would take. We initially arrived with the kind of research and work visa that my husband had to renew yearly, until he changed jobs and got three-year visas. We had been here for a couple of years when we first tried a “discount lawyer” to help us become citizens, and spent a few thousand dollars to no avail. When that didn’t pan out, we got a different job for my husband, while figuring out if we should apply through that employer. As it turned out, my husband didn’t want to apply through that job and ended up getting a different and more interesting job a few years later.

America was an adjustment in some ways, but natural in others.

I grew up in Denmark with cowboy movies, identified with Laura Ingalls Wilder, and considered Niagara Falls to be one of the world’s wonders. Over the years it has been surreal — and yet felt so right — to have visited the home of Almanzo Wilder, gone to Niagara Falls, and petted bison.

I never wanted to be anything but a Danish citizen, but by the time I took the oath here in America to become on paper what I already was in heart, I was ready to not only become a U.S. citizen, but to become a citizen in a land I had made my own.

It took over 16 years to reach the moment I stood at the swearing in.

It was a dark, cold January morning and everyone stayed home so I could finalize the process of becoming a U.S. citizen. It felt very meaningful to be so occupied with humanitarian efforts in our “ancestral” country while ensuring the future of our selves and our kids. Funny enough, my husband was invited for the interview after me, probably due to increased scrutiny into his background check. He was worried about the verbal questions and I told him, laughing, that the whole process had been very respectful and dignified. The questions I was asked had been the easier ones, so I felt like I had over-studied!

Becoming a U.S. citizen during the time of the Syrian Revolution, while serving as a Revolutionary Period Minute Man re-enactor made me feel like everything was coming together perfectly. My children were raised as citizens of the world, with the legal rights of a U.S. citizen (or Danish, in the case of the older ones who hadn’t yet been able to pay the fees to take their Oath of Allegiance). My daughter, Laila, also became a citizen, and says she felt American far before she naturalized.

This upcoming presidential election will be the first time both my husband and I will vote.

While I left my home country very young, and never had the chance to vote, in my husband’s case, free voting was never really an option in his home country of Syria. What is so fascinating to me is that as much as the Syrian regime worked to oppress its people and remove any traces of free thinking and initiative, the Syrian-Americans and Syrians that we know are lovers of freedom, enforcing the reality that humans are meant to live freely. What is so remarkable about the Constitution of the United States is ensuring against alienating citizens from being active participants of the nation — despite ongoing racial and ethnic tensions.

Especially for those of us who aren’t white or wear our religious conviction on our heads, daily life here is not equal and misperceptions often run deep, but the potential is here and we have the constitutional right to pursue and expect equal and rightful treatment.

So, for the gentleman assuming I had just arrived, I sort of answered that I had just gotten off the boat. I felt safe enough to joke with the realization that after having just given a talk on Syria, my organization NuDay Syria and the humanitarian crisis, the audience would still assume I was different and not one of them.

This essay is part of the My Time in Line series, in which immigrants are sharing their experiences of what it’s really like to get legal status.

This article originally appeared on Medium and is republished here with permission.